When I left teaching after 19 years, in 2021, I had no idea that I would return to the sector, let alone to music education. I joined the University of Hertfordshire in March 2022. Currently, I hold a portfolio of roles, including academic skills tutor and visiting lecturer in Initial Teacher Education (ITE), teaching on a variety of programmes (degrees of study). I'm also a visiting tutor, quality-assuring the university-school partnerships and tracking secondary student teachers through their training year. I became familiar with programmes, processes, and the inner workings of the School of Education, and began to understand how this all fitted into the wider university system. As well as this, I completed the Post Graduate Certificate in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education. This opened my eyes to pedagogies and practices in HE, giving me ample opportunity to make comparisons to secondary education, and consider how to reconcile the experiences.

Supporting students with academic writing and their assignments reminded me of my university experience (albeit quite some time ago), with the emphasis on drawing upon a wide range of literature, an evidence base, and critical appraisal. Having been in the classroom for 20 years, the principles of Swanwick, Philpott and Spruce always informed my practice but, unsurprisingly, time for further reading was short. It was enough to keep up with the headlines of new writings and ideas, but the unending demands of being a music teacher limited this. So, when I was offered the role as secondary ITE music lead at the university, I was both excited and apprehensive about returning to this world and having a different impact on music education.

Building foundations

Up until this point, my involvement in training teachers was school-based, as a teacher-mentor and observer. The priorities here are clear: support the trainees in their development of classroom practice across all the teaching standards, offering practical advice and guidance. Teaching music musically (thank you, Keith Swanwick) was also a priority.

Helping trainees gain confidence in making music with secondary pupils has been central to my practice, thanks to my own superb PGCE experience under John Finney. As a mentor, there is little time to explore the pedagogies behind these practices, and the trainee was not always exposed to this. I reflected on this as I gained my bearings and considered the role of a secondary music lead in a student teacher's journey.

What resonates strongly with me is the difference between the terms Initial Teacher Education and Initial Teacher Training – the latter being favoured by the Department for Education. In practice, the two are interchangeable and neither is right or wrong, with the former often being used by university-based providers. In my view, the whole package of becoming a teacher (school-based and provider-based) is probably best described as ‘training’, and we do often refer to trainee rather than student teacher, though mainly for ease.

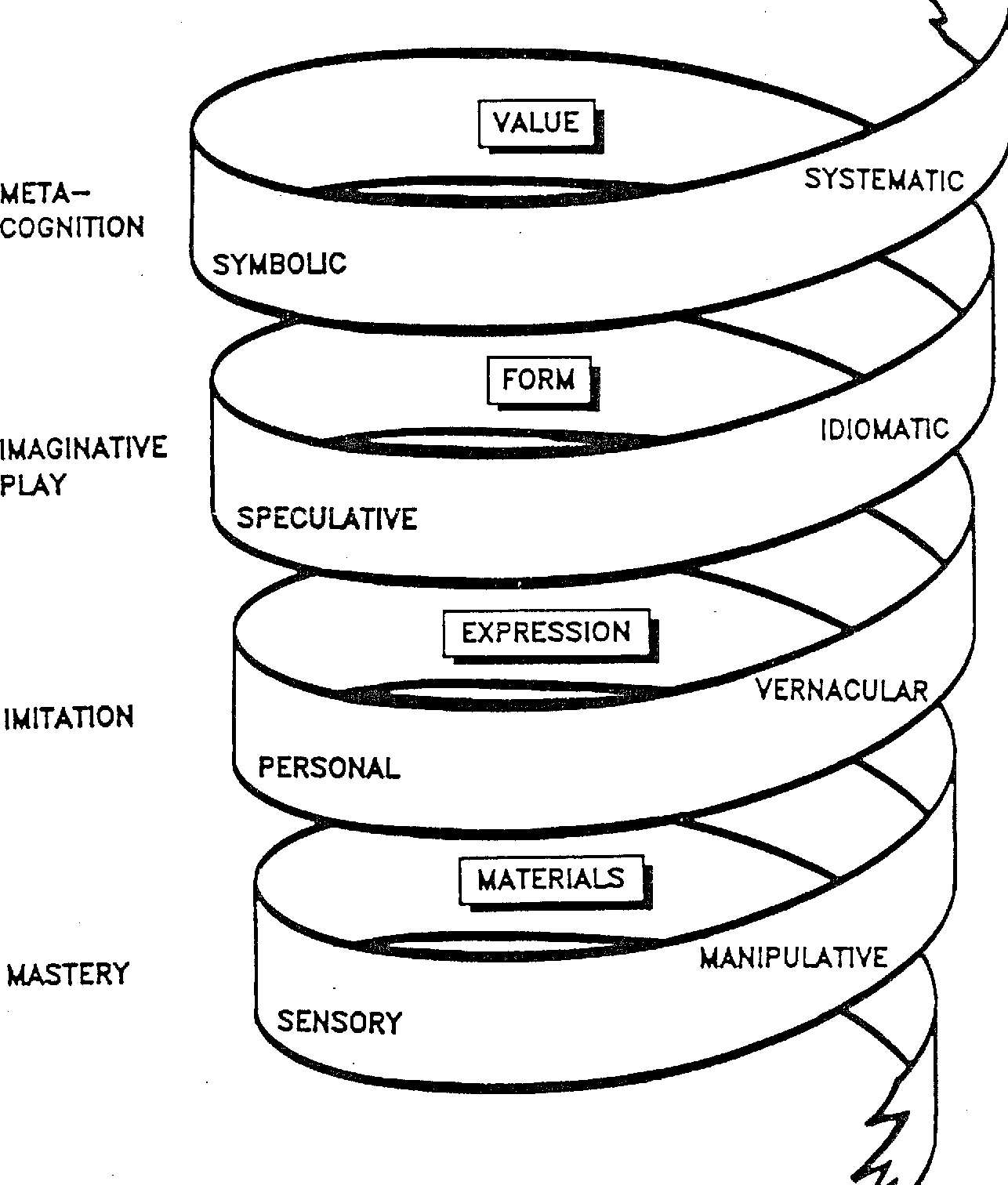

As a module lead at a university, however, I believe that my role lies in the education part. The PGCE is a Level 7 qualification, which requires students to demonstrate critical thinking: drawing on an evidence base and considering the impact of this on their own practice. University is the best place to explore the pedagogies underpinning music education, as well providing an opportunity to explore current research and reflect upon all this knowledge. I see myself as a conduit between research and classroom experience. Not only is it my role to introduce the trainees to Swanwick, Philpott, Spruce, Fautley and others; it's my responsibility to connect their ideas to the practice of music teaching, and consider what these pedagogies look like in the classroom. Most of my role is considering the WHYs behind the HOWs that they are learning in their school placements, as well as reflecting on the music education landscape. The Swanwick-Tillman spiral of musical development

The Swanwick-Tillman spiral of musical development

Universal training

Connecting pedagogies to classroom practice is where misconceptions about a role like mine begin. Recently, I was asked about whether I prepared trainees for specific exam boards and qualifications. My answer was that my focus is on the pedagogies behind musical music-teaching, and that I support trainees with connecting these to a range of classroom experiences from KS3 to KS5, which includes a range of exam boards. But I do not set out to cover specific areas.

I am not the toolkit (although one of my books, How to teach secondary music, approaches this). I believe this is the role of the school placement and the experiences on offer. That said, it is inevitable that, along the way, I model strategies and introduce resources which will be useful for trainees. It is important to me to be a musical role model and demonstrate what musical practices look like, giving the trainees a sense of what it is like to be in their pupils' shoes when making music. I also see the university as a safe place to reflect on (not judge) the range of school experiences that trainees have, comparing approaches as they develop their music teacher identities.

After only a year in this role, when I consider my training experience and my curriculum, I am confident that the trainees will enter the profession with a philosophical underpinning to their aims and goals in music education, and to the kind of impact they want to have. When times were challenging in my career as a music teacher, I returned to these philosophies to steer and reset my course. Without them, I might have left the profession sooner. I genuinely believe that a university-based ITE course fosters longevity in teachers, giving them a foundation on which they can develop their practice and, of course, conduct their own research.