Tech Reviews: Practising jazz

Dale Wills

Wednesday, March 1, 2023

Searching for tech that can help your students practice jazz, Dale Wills outlines some feasible options that could help in the practice room.

I spend a lot of time talking to students about practice. Back in my secondary school days, the priority was simply to get my students into a practice room – if they managed to set a goal for their practice session, so much the better. Working in tertiary education, with the concomitant time pressures, I find myself increasingly talking to students about finding the most e˛ cient solution for their practice goals.

There is something unique about the space jazz practice occupies in music. Unlike classical and rock pedagogies, which (according to the great Wendy Hargreaves) separate creativity and realisation into discrete activities, jazz involves integrating a generative musical approach. Pressing's ground-breaking study ‘Improvisation: Methods and Models' (1988) identified three components to the way musicians evaluated their options: input, processing and decision-making. This seems a nice model for contemporary jazz education, so I was interested to see how the market for practice apps supports this approach.

Input

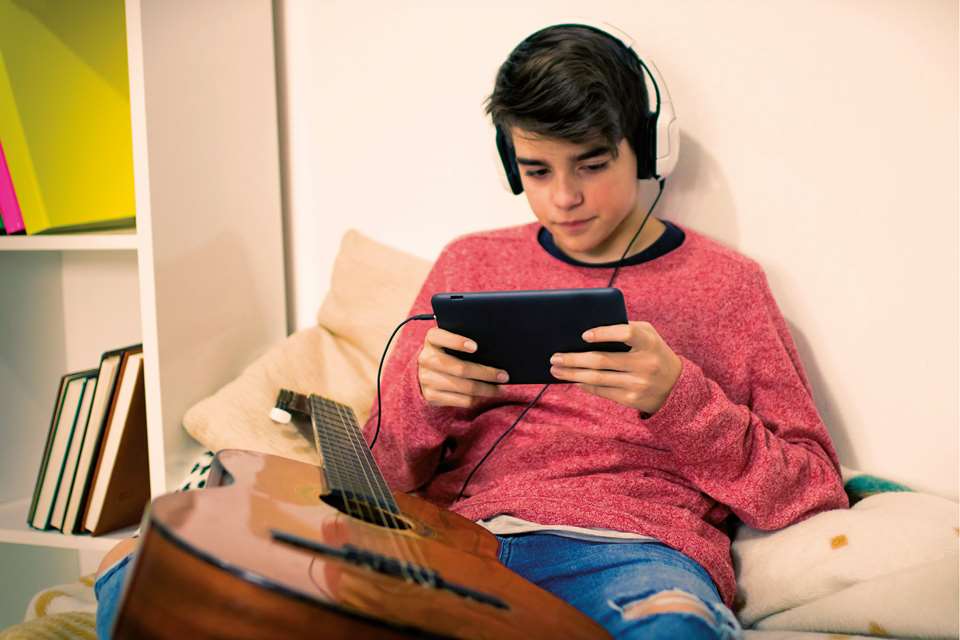

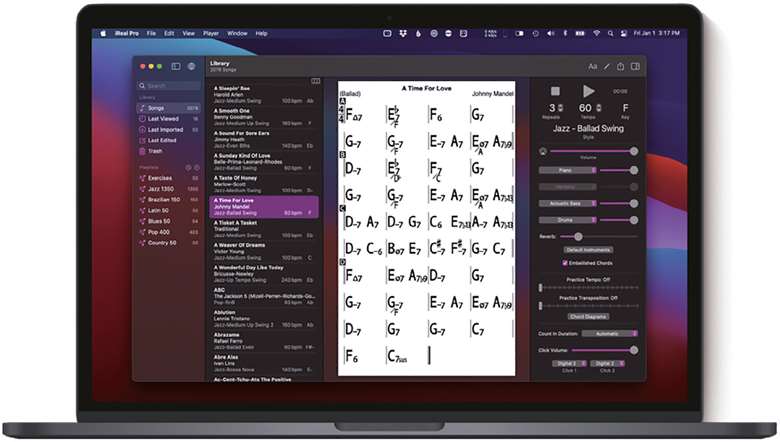

Before a young jazzer can be let go into the world of improvisation and creativity, they need a firm grounding in the grammar of chords and scales. At the top of the list of practice apps, Massimo Biolcati's iReal Pro is still the first port for many players looking to learn their grammatical ‘chops'. Jazz and session drum maestro James Edmunds recalls, ‘Trevor Tomkins, who founded the GSMD and RAM jazz courses, had one simple rule: any one thing you want to learn – learn it in every single possible permutation.' iReal, for those unfamiliar with this go-to app, has a simple premise: what if the whole of jazz literature were available with customisable backing-tracks?

Biolcati's early experiments back in 2009 involved reading conventional notation for each chart. He soon realised that that solution was unworkable, especially for smart-phone displays. The interface was simplified to chord sheets, and iReal was born. Biolcati balances a career as a bass player alongside his software-developing sideline, so it's little wonder that iReal aligns with Tomkins' philosophy so neatly. The tracks for each chart, downloadable from an ever-expanding community-based forum, allow the musician to change tempo, key and even style of the playback backing-track. The app was originally designed to allow jazzers to practise ‘soloing' over a realistic backing. The real genius of the setup is to allow users to mute individual instruments in the backing-track (usually guitar, keys, bass and drums), giving me the experience of playing with a portable ‘trio', rather than having to play over someone else's version.

The app supports searching user forums for charts within the interface, although the search feature can be somewhat ineefficient. Better results can often be achieved by searching ‘song title iReal Pro' in a browser, and importing the files. The forum content has grown far beyond the original Real Book jazz standards, to incorporate classic rock and pop, as well as a reasonable selection of recent chart hits.

iReal pro is still the most popular platform for this type of accompanied practice, and has been on my go-to list for many years. There's something in the slightly inflexible nature of many of the community-added tracks which, while functional, fail to inspire me on repeated visits. Coupled with the £13.99 price tag, I felt that it was time to see what alternatives are currently on the market.

Processing

For players looking to focus on soloing, I was pointed to the Impro-Visor by Scott Jenkins, horn player with the irrepressible Jive Aces. Jenkins is one of those players who always finds an imaginative soloing solution that seems to fit the chart like a sonic slipper. Impro-Visor initially looks like another iReal, but the genius comes in the AI ‘lick generator'. Enter a chord pattern or lead-sheet and the algorithm will generate a potential solo, based on a series of standard ‘licks' and general jazz vocab.

The platform also provides an impressive level of customisable backing-tracks; the lead-sheet can be used as a springboard for a range of different styles, bassline licks and shapes, supported by the usual customisable tempo and key facilities, with one particularly useful feature – the ability to loop individual sections of a chart. This allows jazzers at the beginning of their journey to start building up a ‘grammar' of jazz. The software offers a range of different soloing styles based on iconic jazz musicians; some of them constructed by a vast user community, some of them the result of reinforced machine learning.

This brings up an interesting philosophical question about the role of imitation v emulation in creativity. Some of the results from Impro-Visor are near-transcriptions of famous solos – particularly Chet Baker, whose work I spent many hours transcribing at the start of my jazz journey. Others are much more original; the Tom Harrell algorithm in particular goes far beyond the lyrical, measured phrases for which the trumpeter is famed. Removing, or at least truncating, the process of transcription for young jazzers also removes the evaluative step that helps musicians make the jump from imitation to emulation in their own playing.

Transcription is one of the cornerstones of jazz education. I have several notebooks piled in the corner of my studio filled with pencil sketches of moments from Lennie Tristano to Yuja Wang. It can be a particularly esoteric skill – for many musicians, the audiation skills underpinning this art do not come easily. Discussing various approaches, Scott pointed me at Transcribe! from Seventh String software.

There are several programmes available which offer to help with transcribing audio recordings. The art of rendering a waveform into MIDI data is still in its infancy. The underlying maths is quite mind-blowing, and the results are frequently less helpful than starting with a pencil and paper. Where Transcribe! differs is that the app does not seek to take the work away from the student. At the heart of this platform is a sophisticated audio player. The player offers the ability to slow down and loop parts of a recording – invaluable if you've ever tried to pick individual notes out of the flights of creation from the likes of Keith Jarrett or Chick Corea.

Transcribe! also offers the facility to micro-tune the recording, enabling me to play along with, or back-to-back to, a recording pitched just off A440 by either the tape speed of the recording or excitable live tuning. Throw into the mix chord and voicing approximations and note visualisations, and you have a powerful tool to speed up the transcription process, without taking the work away from the student.

Decision-making

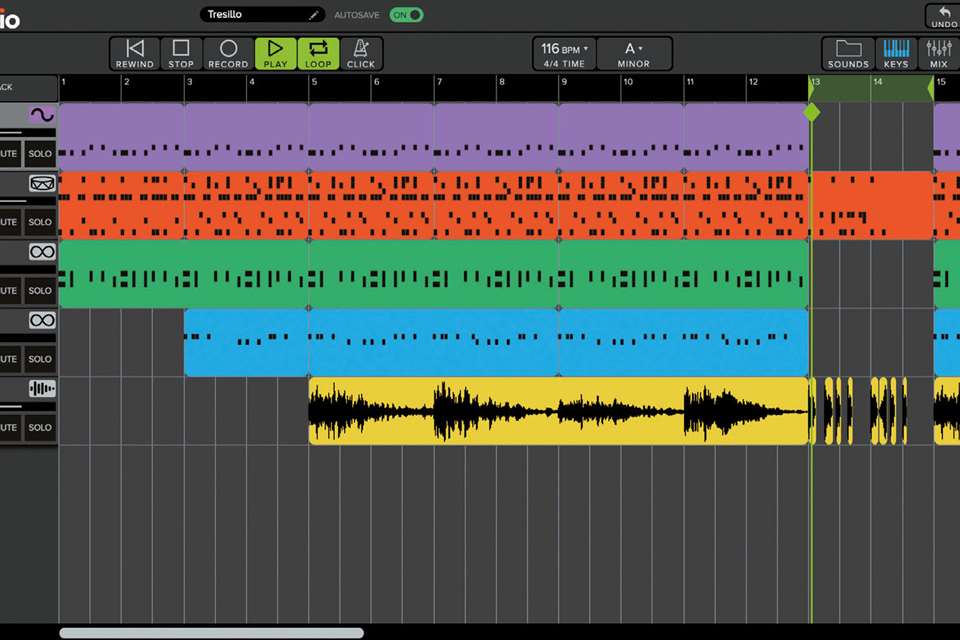

So far we have touched on the three cornerstones of jazz practice: repertoire, transcription and improvisation. For young jazzers, these often feel like three disconnected activities. As these strands start to come together to form the basis of jazz musicianship, musicians need a platform that supports their new-found creativity. JJazzLab is a brave and innovative attempt from pianist/developer Jérôme Lelasseux to do just that.

JJazzLab automatically generates backing-tracks for any charts, providing reliable results, even in the most complex examples. It's a jam buddy to have fun improvising at home, learn new stu˙ or just practise your instrument. It's also a great tool for teachers.

The results are based on a series of audio sample ‘loops'; this avoids the sterile feel of some (most!) of the MIDI based backing-track platforms. There's something reassuringly ‘live' about the JJazzLab track, which I found filtered into my own playing. The display is refreshingly non-linear – much more akin to an Ableton-style ‘cell' approach, which makes for a fluent and reliable interface.

The feature which sets JJazzLab apart is its ability to generate dynamic tracks. Rather than being stuck with a static track in swing, ballad, Son Cubano or any one of the other predetermined styles, the platform allows you to build up and reduce the track over time, programming in variations of rhythmic feel, patterns, comping style, creating a surprisingly musical result. Of all the platforms I have sat down with, JJazzLab feels the closest to working with a live band.

The experience of playing with, and reacting to, live musicians is central to the jazz experience, particularly when it comes to the synergy of creativity and realisation. Another platform which aims to integrate these features is Genius Jamtracks. The platform offers two modes: ‘Practice' and ‘Jam Session'. In Jam mode, the interface gives you two simple sliders for rhythmic and harmonic complexity. At the start of each track, the backing-track starts with a reassuring level of clarity, allowing the player to find the pocket. Once in the groove, the track moves away from the obvious feel, challenging the player to find new innovations. This is particularly obvious with the integration of a range of challenging polyrhythms generated by the underlying AI. This means that no two practice sessions will ever quite be the same!

Finally, in the panoply of practice support, I can recommend everyone tune in to You'll Hear it, a long-running podcast hosted pianists Peter Martin and Adam Maness. Although occasionally a little keyboard-centric, the content takes a refreshingly honest look at practice psychology and methodology from the perspective of both students and working musicians. And in a world where practice is often squeezed in between a thousand other time constraints, I for one am grateful for anything that focuses on how to get the best results.

Find a helpful glossary of terms used in our music tech reviews online.