Traditional music is a deeply creative, rich and varied genre. I’ve been teaching folk fiddle (primarily Irish and English tunes) for many years, my approach informed by the many musicians I’ve listened to, learned with, and played alongside. Given its inherent flexibility, there are countless ways to teach it. Here, I share some of the ideas and practices I’ve found useful along the way.

The aural process

Start by listening. The aural process is absolutely intrinsic to how music is transmitted among traditional players. Notation gives only the merest hint of how a tune might be played; the music (and magic) happens when an individual player introduces, within the framework of their tradition, their own rhythmic and melodic variation and embellishment. Although the vast majority of folk musicians read stave notation these days and will make use of tune books to expand their repertoire, the notation in such collections usually offers no more than the bare bones of the tune. Thus, an ear-based approach is essential for absorbing the feel of the music, understanding emphasis patterns and how to create them, and how and where to use stylistic rhythmic and melodic variation and ornamentation.

This probably all sounds mildly terrifying for musicians primarily teaching classical music, but it really isn’t! Working by ear means engaging in a deeply creative process which can be adapted and developed as you go. Take a structured approach, and the aural process will immediately feel less daunting.

Structured listening

The following suggestions work well for pupils, but also for those of you who may feel less confident working without the dots. These draw out some of the key elements found in many folk tunes.

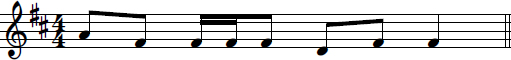

Identify a suitable tune for the pupil to learn. It’s a good idea to begin with a common tune-type such as a reel (usually written in 4/4, but with a 2/2 feel) with a simple AABB structure. The Earl’s Chair (Ex.1) is a good example:

Ex.1 The Earl's Chair

Ex.1 The Earl's Chair

Listen through to a recording of the tune several times. There’s a lovely version by the great Kevin Burke on YouTube; follow the link below. What patterns can you and your pupil identify? Are any bars or motifs repeated? Is the B music higher in pitch than the A music? Which beats are emphasised? Does the pattern of emphasis stay the same throughout? Can you hear any variations when the tune is repeated? Answering these provide valuable building blocks. Listening to tunes on mobile phones is great for this process; if everything feels too quick, there are several apps available that allow you to slow down tracks without altering the pitch.

Learning the tune

Ideally, your pupil will have listened to the tune sufficiently to be confident with the characteristics listed above and to be able to ‘sing in their head’ all (or most) of the melody before trying it on their instrument. This also applies to you, so that you can begin teaching the tune entirely by ear. However, it’s fine to have the sheet-music to hand as back-up if you don’t feel entirely confident.

The process of teaching/learning the tune by ear is essentially one of playing and copying until everything sticks. Don’t worry about bowing, emphases, etc. at this point; just focus on the notes. Start by playing one bar to your pupil for them to copy. Repeat this until the bar is secure, then play it together several times. Then move onto the next bar. Then add the two bars together. Once you’ve taught all of the A part, play ‘call and response’ with two-bar sections; now swap over. Remind the pupil of any patterns you both heard when listening to the tune; for example, are any bars the same? Work through the whole tune in this fashion.

Bringing out the emphases

As soon as the notes are secure, focus on the underlying pulse of the tune and on which beats are emphasised. Most traditional melodies are dance tunes, and the ‘feel’ – the lift, lilt, swagger or groove – is absolutely the priority in this music.

Let’s go back to listening to The Earl’s Chair to check which beats are emphasised. In Kevin Burke’s recording, crotchet beats 2 and 4 are dominant (a common musical trait in many regions of Ireland). Ask your pupil to clap these beats with the recording. Get them to walk around the room, stamping on the dominant beats. Ask them to play a tonic drone using separate bows, gently accenting beats 2 and 4. Then ask them to try the same but using two bows per bar, so that beats 2 and 4 are ‘pulsed out’ in the second half of each bow. See if they can play along with the recording/you playing the tune, maintaining this pulsed bowing.

All in the bow

How to keep these emphases when you play the tune? What the right hand does in this music is absolutely key, since bowing is much more rhythm-driven than in classical music. I think bowing in traditional music is much more akin to how a guitarist strums.

There’s no right or wrong way to bow traditional tunes, as long as the emphases are felt and the music stays vital. Different players will create the same effects doing different things, and vice versa. However, there are certain patterns and techniques which can help create the appropriate character. And, although the context is different, good, basic bowing technique – understanding bow division, varying bow speed and bow weight – is just as relevant in traditional playing as it is in classical music.

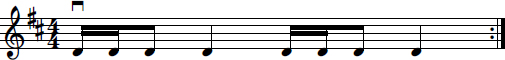

So, returning to the question of how to maintain the emphasis on beats 2 and 4 when playing the melody of our reel: many players do so by ‘bowing across the barline’ and ‘bowing across the beat’ so that beats 2 and 4 fall on separate bows, with scope to use more bow on these beats. Ex.2 shows how one might bow bars 1 and 2 of The Earl’s Chair:

Ex.2

These patterns of bowing across the barline/beat also crop up in jigs, so it’s a good idea to get them up to scratch. Ex.3 suggests a simple way to practise such patterns.

Ex.3

Ornamentation

What other ways might we emphasise certain beats? Both left-hand and right-hand ornamentations are used for this purpose. A common bowed ornament across many regional fiddle styles is the crunchy ‘bowed treble’, as in Ex. 4. In its simplest form, the three notes are played all on the same pitch, as added here to beat 2 in bar 3 of our reel.

Ex.4

When a tune is played at speed, this ornament is rapid and percussive. Most players find ‘trebles’ easier to start on a down-bow, about a third along from the point. The bow should barely move for the three notes, although there should be roughly twice as much bow on the first note. The ‘crunch’ comes from first-finger pressure, applied to the first note and released at the end of the third note.

Ex. 5 provides a way to begin learning to play bowed trebles; start slowly then gradually speed up over time. Make sure that the bow stays a third along from the tip. Once this exercise is rhythmically sound, introduce the first-finger pressure. Take it slowly; the whole point of this ornament is to add rhythmic interest and emphasis, not uncertainty!

Ex.5

Left-hand ornaments

There are countless varieties of left-hand ornament across various fiddle traditions. Again, most of them have an essentially percussive function, as in the ‘cuts’ or ‘taps’ involving rapid finger flicks with minimal string contact. A quintessential left-hand ornament from the Irish tradition is the ‘roll’, as in Ex. 6, which is a series of five notes played very rapidly, with the second and fourth notes barely sounded. It tends to be used interchangeably with the bowed treble, as presented here.

Ex.6

Rolls take a lot of control to get right. Initially, practise a second-finger roll, starting on F# as in Ex.6, playing the five notes slowly. The fingers eventually need to be very fast and light, so practising in dotted rhythms to increase strength and agility can be helpful.

Varying tunes

As well as providing rhythmic interest, adding ornaments introduces basic variation. And variation – of the melody, the rhythm, sometimes even the tonality – is part and parcel of playing traditional music. There are simple starting points for variation and improvisation, such as adding passing-notes between notes a third apart or playing the melody down an octave (frequently possible with the B parts of fiddle tunes). More advanced folk students can learn a lot about varying tunes by transcribing versions by great players.

This takes us back to where we started, namely the importance of listening. Listen as much as possible, to fiddlers and other instrumentalists. Go to sessions, go to workshops, play along with recordings, and play with others as much as you can – teacher and pupil alike. Embrace the aural tradition!

Further resources

- Cranitch: The Irish Fiddle Book: The Art of Traditional Fiddle-Playing. Ossian

- Griffiths, ed.: Traditional Fiddle: A practical introduction to styles from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales. OUP

Recommended listening:

- Kevin Burke, incl. performing The Earl’s Chair: tinyurl.com/swaf4nd8

- Liz Carroll

- Liz Doherty

- Martin Hayes