In March 2020, just weeks before the first lockdown of the COVID pandemic, I released a body-percussion tutorial, Body Beats, covering many ideas I've developed in workshops. Much of this includes material based on literacy as a stimulus for body-percussion composition – an approach developed through collaborations with literacy authority Pie Corbett of Talk4Writing. In early years settings, this involved taking children's names, nursery rhymes or books and exploring the rhythmic potential of words when spoken out.

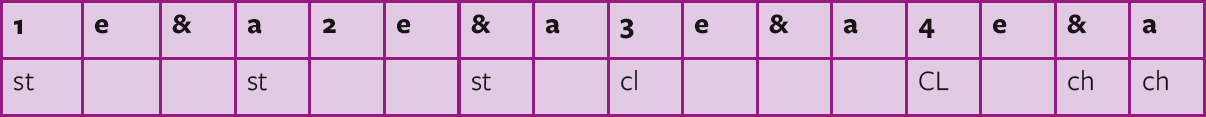

Having worked with standalone body percussion, I was intrigued by the possibilities (and challenges) of body percussion in vocal contexts – after all, it's all just ‘body music’ (a term I'd heard used by Keith Terry of the US arts organisation Crosspulse). An opportunity to explore this came during a collaboration with the choral-composer team of Alexander L'Estrange and Joanna Forbes L'Estrange. The project, Green Love, combined body percussion and voices for a virtual performance. In this instance, the body percussion came first, with Alexander and Jo basing sections of the work on grooves I'd composed. One of these was an adaptation of a west-African djembe pattern, using stomps, chests, clicks and claps representing bass, slap and open tones:

st=stomp, cl=click, CL=clap, ch=chest

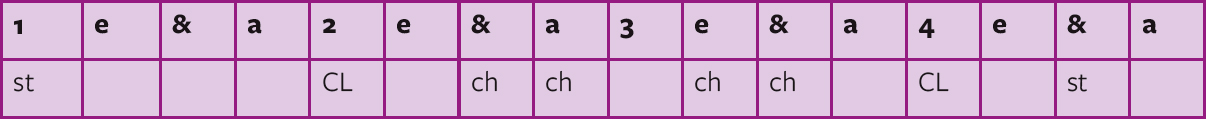

st=stomp, cl=click, CL=clap, ch=chest

Another groove had a funk/hip-hop feel, mimicking elements of a drum-kit:

According to the composers: ‘The advantages of incorporating body percussion with vocals are manifold: it helps choirs to get properly into the groove of each song, making them less likely to rush ahead of the pulse; it provides an exciting visual element for the audience while also giving the performers something to do with their hands; it adds an extra texture within the choir's sound; and it encourages choirs to learn songs by ear, which is great for their general musicianship and performance skills.’

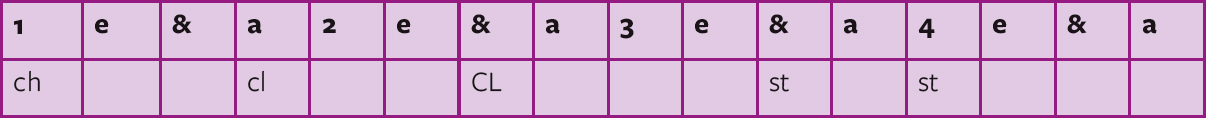

In a separate project, I based body percussion on an existing vocal score, working the other way round. Working with schools across the Girls’ Day School Trust (GDST), we explored the cantata Along Came Man by the composer and educator Lin Marsh. The phrase ‘Along came man’ lent itself to the 3/2 son clave rhythm, which I adapted onto body percussion:

With the clave as the starting point, I asked the pupils to develop their own ideas, exploring visual as well as musical possibilities. I find that when movement is the focus, it can become a real highlight of a workshop, especially when done collaboratively in groups. Ruth Coles, head of junior music at Blackheath High School, agreed, saying that body percussion brought ‘a fantastic element of collaborative movement’. She said it also provided ‘the most resonant sound in a large concert space’.

In a third project, involving the National Youth Boys' Choir, I explored adding body percussion to a brand new commission, integrating it at the start of the process. For a performance of the choral work I am. We are., by Oliver Tarney and Hazel Gould, the remit included composing suitable polyrhythmic body-percussion parts, and making these parts suitable to be learnt in three days, and performed confidently. In addition, I overlaid the vocal parts with body percussion, writing parts to complement the rhythms of the vocal lines and, partly, to fit into the bars' rests.

With choral director Lucy Joy Morris, I developed ideas that included using vocal entries to prompt body-percussion phrases for each part, making the vocals and body percussion easier to remember and creating space within the piece for all parts to be heard. This combination also brought a strong visual aspect to the piece, with unison and sectional hand/arm movements with claps and clicks.

The choir performed the work at London's Royal Albert Hall three days later, and later recorded a performance for video.