Music health

It is essential for us to understand the role of music in the everyday psychology of our pupils. In my teaching experience, I have often had adult students who have described their piano lessons as a mindfulness exercise rather than ‘just’ learning an instrument. Equally, I have often suspected this for several younger students who demonstrate an almost overwhelming keenness in their lesson – engaged by musical games, creating simple and unusual sounds and discussing music as a whole.

As a teacher, I must admit, this realisation has helped me make a ‘U-turn’ in my teaching technique, which until then was purely and strictly classical. Of course, that does not mean I do not want my students displaying a nice posture or having round hands when playing scales – and neither that I do not have academic expectations of them. However, it has changed the way that I am projecting these expectations, while trying to accept each student's individuality and personality. With the current crisis, everyone's everydayness has become radically different. And if we, as teachers, do not take this into account, who will?

Broken routine? That's great!

Everyone's routine has dramatically changed. While some people enjoy and embrace change immediately, most don't. Especially children. My first thought, when lockdown was on the horizon, was that somehow we must continue living ‘as normal’. I found all students and parents enthusiastically agreeing with me. Of course, that would not mean that we should act as if nothing has changed. Everything had changed and our teaching must change too, to fit the new circumstances. Luckily, as it happens, change is good for learning. As Olson explains in The Invisible Classroom, ‘One kind of experience that grabs the bottom-up attentional circuits of the brain is novelty, and this can prove a significant challenge and powerful ally in class’ (Olson, 2014). And while a sudden change can be distracting and frustrating for pupils, if the struggle is profoundly understood by the teacher, it can be turned around and used for the benefit of the student and the learning procedure itself. It could almost feel like a new learning ‘chapter’, which is potentially more engaging and exciting than the preceding ones.

First week of online teaching

When a crisis first hits, our automatic concern is usually: ‘I have to provide for my family’. Many things come after this; ‘we have to continue our normality’ – whatever this means to each one of us – or the more optimistic ‘let's think what use we can make of this?’. Personally, my first week of online teaching was quite stressful. I did not know how many of my students will drop the lessons, or how many would have the necessary equipment to continue. It was a completely uncharted territory. What can I do as an online teacher that I did not do before? And, equally, how can the students learn and enjoy more?

Increasing enthusiasm in numbers

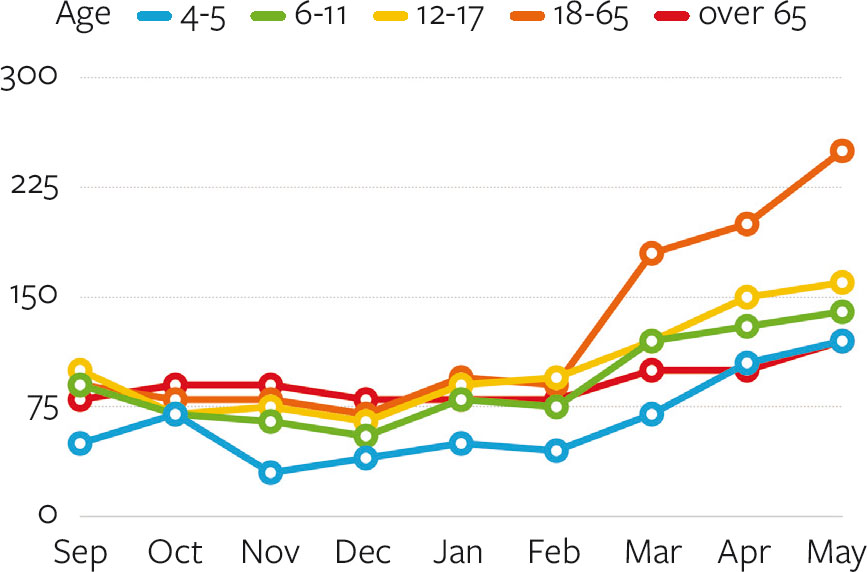

As the second week of quarantine passed by, I started noticing a pattern: students were happier than usual to have a lesson, looking forward to this time of the week (even logging in earlier to make sure they will not miss it!) and more parents mentioned casually that the ‘music lesson is now the highlight of the week!’ Of course, this was mainly due to schools being closed, lack of usual homework and so on. Be that as it may, it seemed to me the change was too big to ignore. The following graph shows the average of piano practice weekly (in minutes) per month in five different age groups of my 46 students:

This may look like a reasonable increase, if you consider how much more free time the students had in the new situation. However, I have never thought that the main reason for not practising was lack of time, but rather motivation.

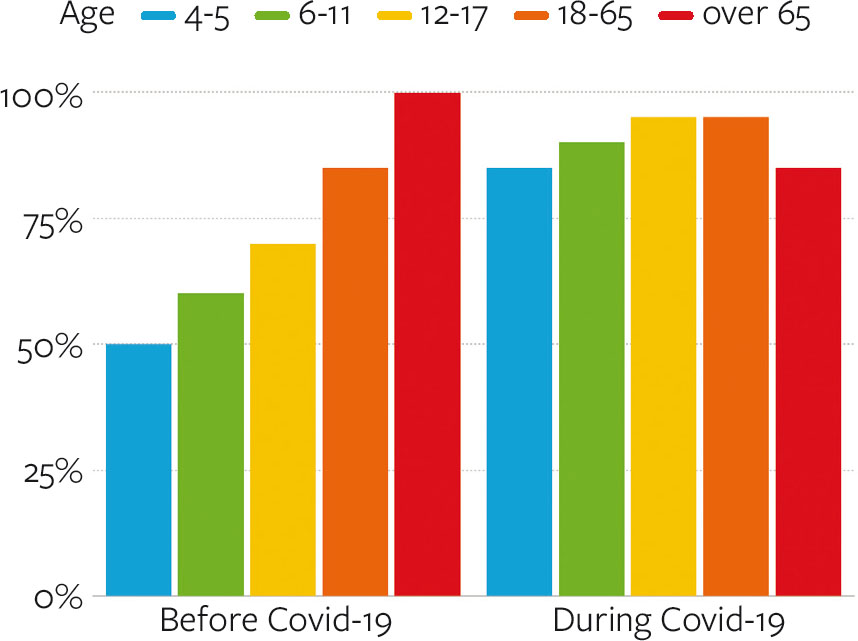

The following graph supports this thought, too. It shows the average of actual playing time within the lessons, excluding chitchat and other forms of student procrastination:

With the exception of the over-65 age group that actually chatted more than normal, all other age groups seemed way more eager to get playing rather than wasting time. They showed deeper focus and understanding of the new elements of each lesson. In the next few paragraphs we explore why.

Don't get too comfortable

A huge benefit of the online lessons is having two pianos at our disposal. This not only means that we have more pianos than normal but also that the students are playing and learning on their own pianos. As much as I want to convince my students to get used to playing on different instruments, I can hardly hide how much I love to play on my own piano. In fact there are studies that prove that ‘people remember more of what they studied when they return to that same study environment’ (Carey, 2015) The psychologists DR Godden and AD Baddeley led an experiment where they asked eight scuba divers to ‘study a list of thirty-six words while submerged twenty feet underwater.’ (Carey, 2015). An hour later, the researchers divided the divers in two groups that took a test on the words they had studied, in two different environments. The first group completed the test on land, while the second group had to dive back down and take the test underwater. The results were stunning: the second group did 30 per cent better. The psychologists concluded that ‘recall is better if the environment of the original learning is reinstated’ (Carey, 2015) even when the environment is not too comfortable. Additionally, the same researchers have argued that we learn much better – and often stay more focused – in seemingly less comfortable environments. So maybe this brilliant idea that we all had while driving in the traffic, or this amazing discussion we enjoyed while being in a noisy bar now start to make more sense. This is why I am insisting that we should not focus on how many cameras we have, or if the sound or image quality is perfectly crisp. Prioritising comfort is not always helpful.

Time for a complete makeover – and how to achieve it

In order to maintain and utilise (or even amplify!) this circumstantial new wave of enthusiasm, we need to be inventive, inspiring and use novelty. Each student is different and therefore it is not realistic to have one checklist for all the different student groups. However, this is a tips list, which so far has worked with the vast majority of my students, regardless of age, ability and targets.

A practical guide

Initial set up

Firstly, we have to set up our new ‘classroom’. This has been discussed at length in recent issues of MT and needs no further repetition; see May and June, plus p26 and p32 in this edition.

Screen-sharing

Sight-reading can be tricky, as we cannot expect our students to have the music libraries we do. However, books all teachers have in their computers become instantly available via screen sharing, as well as online resources like Scribd, Amazon kindle and many others. Whether your students are using tablets, personal computers, laptops or even phones for their online lessons, I guarantee that sight-reading a few bars per time is more than possible.

Play-along tracks

One of the big challenges of online lessons, however, is playing a duet with your student. Sadly this is not truly possible yet, due to Internet latency and sound quality. Here is an idea: record play-along tracks for your student. It could be something as simple as a recording of you playing your duet part on your phone, or even a fancy arrangement in GarageBand (or other arranging software). It would motivate students to practice more, and the same tracks can be used with multiple students who are playing the same pieces.

Other software

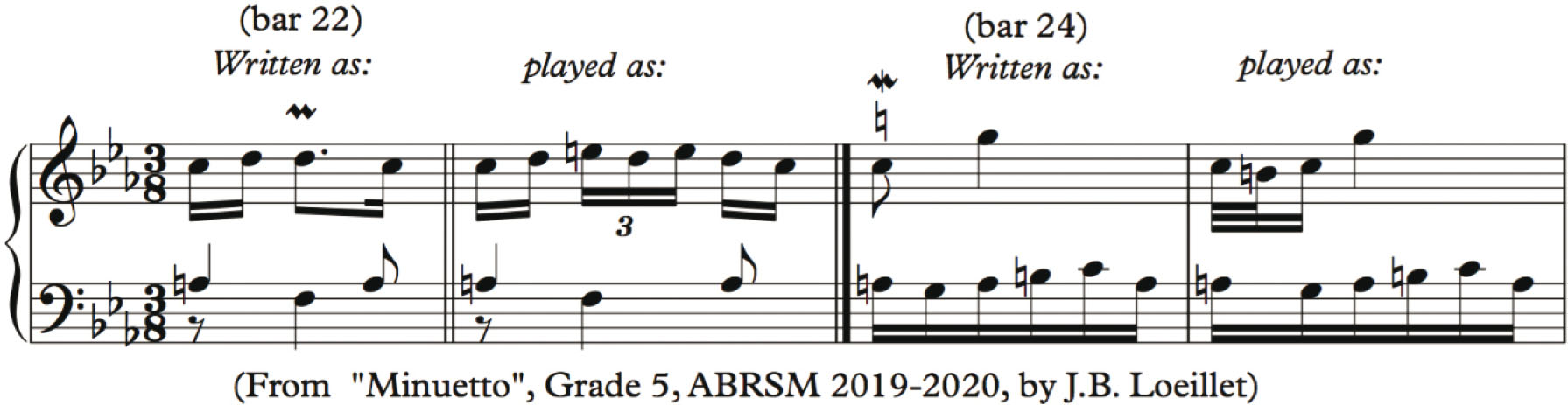

In this following example, which I sketched while giving an online lesson, I explained to my Grade 5 student the difference between two trills (see excerpt below).

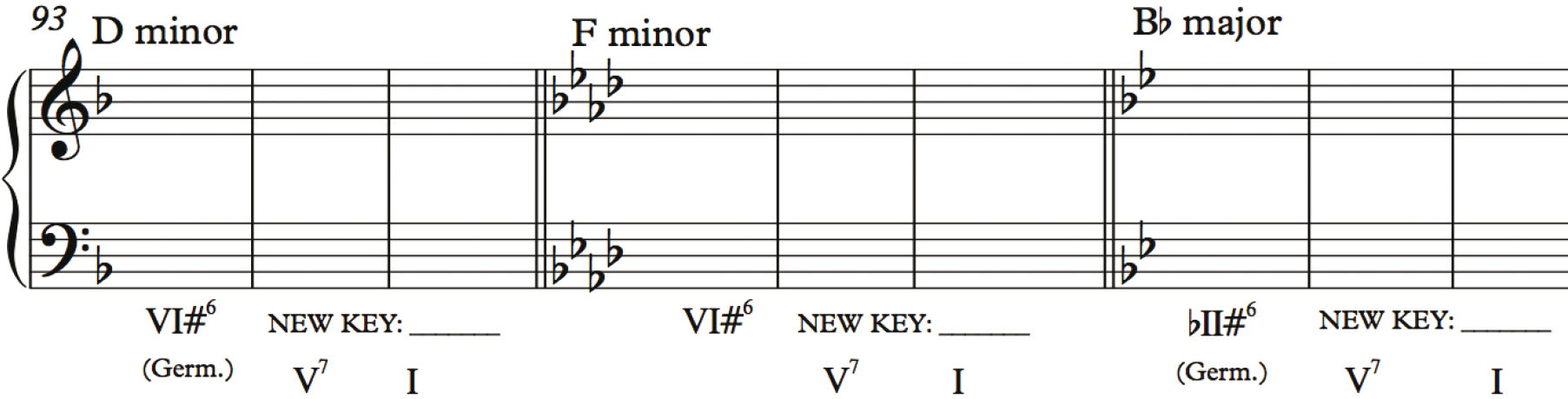

Music notation software is quite easy to master and can be extremely useful. If you are teaching music theory, set up a ready-to-go project to use for the lesson and homework too. The example above shows my ‘working desktop’ for a composition lesson, where we are currently covering augmented 6th chords in modulations.

Notation examples take minutes to make and can be easily transformed in order to make a nice homework exercise that can be emailed to the student after the end of the lesson. (See p32 for advice on corresponding with students during remote tuition.)

Missing resources

Every generation is different, and if we do not accept this, as teachers, we have failed. As Alison Daubney explains in her book Teaching Primary Music, it is of great importance to relate to today's music everydayness. In the chapter ‘Music in a fast-changing world’, Daubney describes how differently the new generation is accessing music: instantly, on demand, so much more broadly than we did at their age. It truly reminds me how many times I have become frustrated with a student who, despite not having practiced at all what they were supposed to, has spent hours and hours on the internet learning a particular piece from a poorly made YouTube tutorial. And then I realise: it is because this is in ‘their language’. It is more accessible and easier to understand (even when it is kind-of amateur). And there is nothing wrong with it. ‘Music has universally existed across time and place. {…} The informal environment where children function musically outside of formal learning environments in and out of school, is where much musical learning and engagement take place’ (Daubney, 2017). Do the online lessons approach this kind of ‘informal’ place? Would this benefit learning in a different way? If used sensibly, I think yes. Absolutely.

Encourage student-led learning

Learning new pieces is harder, as this is when students need us more. Be that as it may, one of the things that struck me from the first day of online teaching was how easily some students started correcting their own mistakes and taking notes whereas, before Covid-19, when I was next to them, they would hardly pick up the pencil or even try to actually read the notes unless I read them for them. In other words, they started acting more like teachers. Most of my students' sight-reading ability improved dramatically as they felt the need to ‘survive’ by themselves, so to speak. This is more profound in younger students who are usually being ‘spoon-fed’ more often than adults. Milner and Bateman argue that ‘viewing children as preparing for adulthood rather than viewing them as people in their own right {…} means that their capacities for understanding and reasoning can be underestimated, and they can be deemed incompetent to make decisions.’ (Milner and Bateman, 2011). This is a very important point, and it will definitely change the way I teach, even when we go back to face to face lessons. Sometimes we need to get these ‘bike stabilisers’ off and have more trust, both as teachers and as students.

Build a community

If there is a period that we need our community to be strong, it is now more than ever. Therefore why not build an online community with your students? Maybe host short online concerts? Also it is worth trying group lessons with same level students, discussing tricky passages in exam pieces, scales, and broken chords. Another idea could be publishing a newsletter among your students, to keep them updated regarding music news, online events or even news about the exams. This also applies to building a community among teachers, too – see p14

Epilogue

The main purpose of this article is to encourage a period of consolidation; to ensure that we continue to use the skills developed during this time, in order to become better teachers. Hopefully, by the time you read this, we will be near the end of the quarantine and getting ‘back to normal’. But maybe instead of ‘back’, we can go ‘forward’. Within this challenging situation, let us learn, change, improve and do better. It was frankly quite unfair that we had to develop this new toolbox of skills overnight. It felt like we were given an amazing modern ship but we had to test-drive it in a storm. The question now is, when the storm is over, will we have learned how to calmly sail?

It is our duty, as educators, to use every tool we have available in order to provide the best teaching possible. It is within our skill-set to ‘read’ each situation differently and always keep our teaching up to date. We can all find a way to thrive within – or despite – a ‘new normal’.

Further reading

Olson, K., 2014. The Invisible Classroom. New York: W.W. Norton.

Daubney, A., 2017. Teaching Primary Music.

Milner, J. and Bateman, J., 2011. Working With Children And Teenagers Using Solution Focused Approaches. London: J. Kingsley Publishers.

Carey, B., 2015. How We Learn. Pan Macmillan.