I came to the point of writing this article by stumbling upon something that appeared to work. I studied composition formally and now write music for concerts, film, TV and games. I was employed by the thriving Norfolk Music Service to go into a school to support its music teacher with composition. I did things the only way I know how, but luckily this seemed to work and it had a positive impact on exam results. I now visit many schools and ‘this’ is still working, so I thought I’d write an article that may help others, showing, if anything, that we are all in the same boat.

Make a link

Many pupils at school don’t seem to realise that the subject ‘Music’ on their timetable is the same music that they hear on their playlists, on the soundtrack of movies, adverts, computer games, radio… the list is endless. Generally speaking, I don’t think many people, particularly those who have power to make decisions, realise how much music is an important part of life, but that’s a topic for another time.

I have seen Year 9 pupils coming into a music classroom saying ‘I hate music’ as they remove the buds from their ears and turn off their music player. If we can make pupils see the subject we are passionate about at school as part of the same music they experience on a daily basis, this will help us get through to them. As far as music exam students are concerned, the same linking is vital. Pupils study set works from many genres, there is the Listening & Appraising, and some A Level students work on Bach chorales, yet when they start their composition it’s almost as if this is an altogether separate entity. I try to guide them to see how that melody in Star Wars, Defying Gravity or any other of the set works has shape, line and rhythm, and that it’s logical, singable and memorable.

Understanding that the music that is part of their life (one way or another) is the same thing as the subject of music at school is crucial. Movie scores, game soundtracks and pieces by Bach, Stravinsky, Queen, Louis Armstrong, Bob Marley, John Williams and Taylor Swift, you can argue, are put together in the same way.

Melody writing

I have found that one of the biggest impacts made on exam marks is the quality of the melodies. It doesn’t matter if it’s a pop song or symphony, the form and shape of the melody is far and away the most important thing. There are countless examples of this, from the theme to The Archers or Dvořák’s New World to ‘Happy Birthday’, and these all have a distinct feel and shape to them; we know instinctively where the tunes want to go. Yet many melodic lines in student compositions have uneven bars, little form or unsingable shapes and patterns.

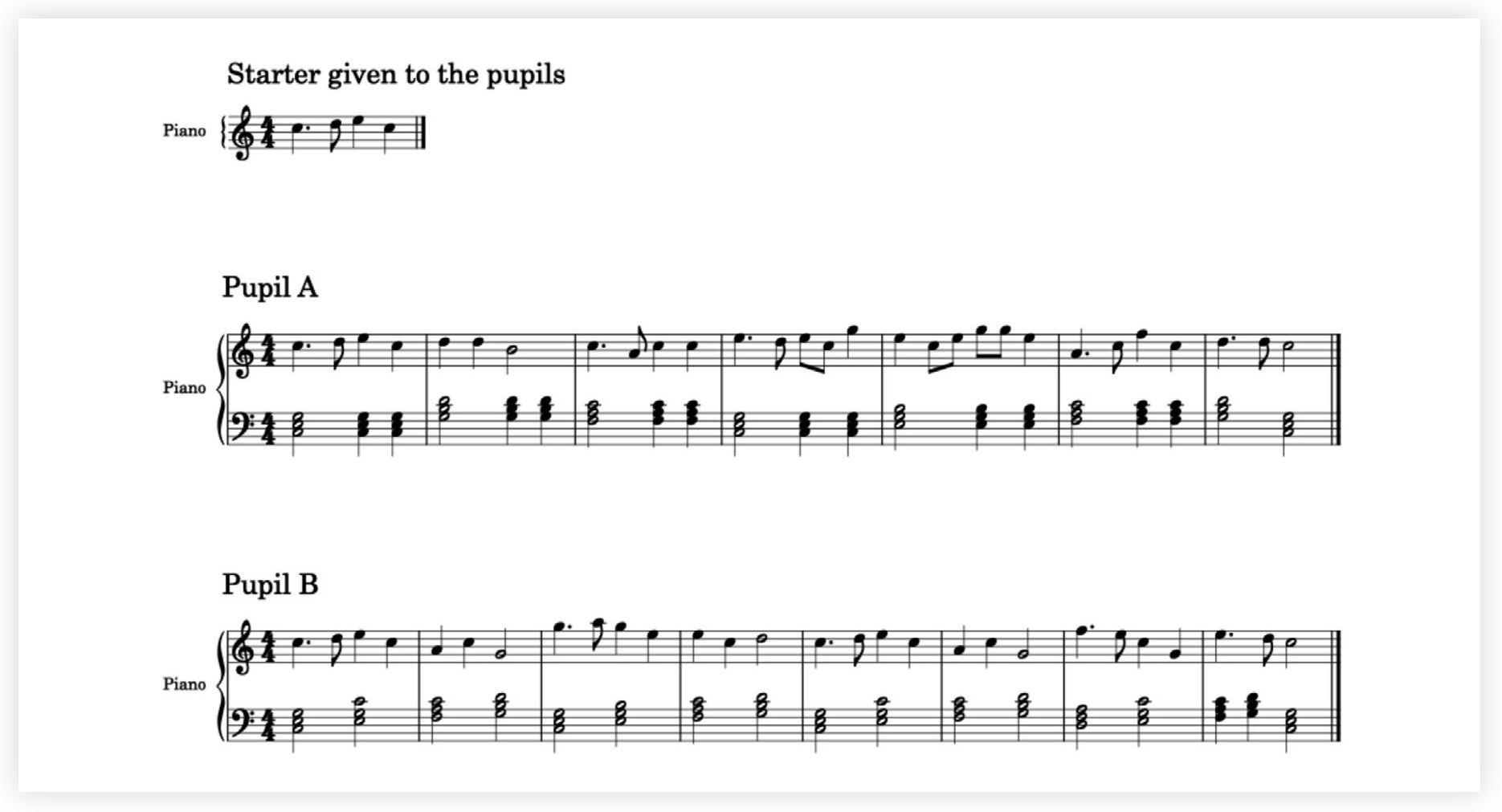

I gave two similar-ability students the task of quickly putting together a tune and simple harmony. I set them up to work alone and then asked pupil A to write the chords first, and pupil B to write a whistleable tune first. Pupil A wrote a melody that had an uneven pattern and sounded clunky. Pupil B composed a melody that felt right and was useable in a composition. The end results are presented below:

I found that students really can think in melodic lines and it’s worth pushing them on this. Early on in the GCSE course, I do a lesson on composing simple tunes. I tell students that these are exercises and not part of their composition, and yet many use these exercise-melodies in their final work. It sometimes helps to have them pin the theme, as a starting point, in a computer game or movie scene, and then keep it simple: a two-bar question, two-bar logical answer, then repeat, making an eight-bar tune. I might also ask them to try a limerick pattern (I no longer ask if they know any, after one memorable morning with a Year 11 class), along the lines of:

Dun di Dun di Dun… di Dun di Dun di Dun…

Dun di Dun, Dun di Dun… di Dun di Dun di Dun.

Composition structure

‘Structure’ is such a dull word and seems to sit uncomfortably with the word ‘creativity’, yet I’ve found it to be so important. I think planning is vital, too. Many times I’ve entered a classroom to see students clicking away at the screen, adding notes all over the score. Yet when I ask them what the plan for the piece is, they don’t have one; if asked what the melody is, they shrug and say ‘I don’t know yet’. I’ve also seen introductions to pieces that aren’t yet written.

A couple of teachers have asked for my thoughts on feedback received from an exam board, which referred to pieces in ‘sonata form’ and cadences or other formal devices as ‘formulaic’. I must admit I find this slightly worrying, and I’m sure I’m not alone. Songs that follow a scheme of intro–verse–pre-chorus–chorus–verse–pre-chorus–chorus–bridge–chorus, for example, don’t seem to fall into this category, and yet this is also a formal structure.

I believe we have a responsibility to teach composition technique that includes form, harmony and good practice, and align it with the study of set works and the music we all enjoy every day. I think the quality of the compositions produced are worth this.

Once the pupils have a plan for their piece and a melody plus harmony they are going to use, I take a lesson to discuss what a motif is, and try and spot these in music they relate to. I also try and break the idea that just because I like classical music, I’m not sitting at a desk in a powdered wig and writing with a quill. I’ve found it helps to play stuff from my own playlists and then put on a range of things from Mozart to Metallica, via Marvin Gaye and Miles Davis.

When the motif idea is clear, I ask them to find what the motif is in their piece and make a note of that, too. Then they start the composition.

I try and use notation as much as possible, as it contains so much information for the examiners. If somebody records themselves playing a piece they’ve composed on, say, the bagpipes, the amount of commentary needed to send with this, while showing the composer’s workings, is huge – so huge, in fact, the time spent getting it into notation would be worth the effort.

One size doesn’t fit all

Some teachers I’ve met have made ‘Composition Guide Sheets’ and given one of these to every pupil. However, in my experience, ‘One Size Fits All’ doesn’t necessarily work when it comes to composition. In fact, I have sometimes met students who have written good pieces but are worried about trying to make these fit a guide given out in class.

The most common challenge seems to be the number of instruments used. I understand that we don't want 73 different instruments all playing three notes each, or a nose flute written in an unplayable key and out of range for most of the time – I accept it’s good to have some parameters.

From my own composition lessons I remember being shown that the hardest thing to write for was not, as one would imagine, a fugue or a symphony, it was a string quartet. The quality of the functional harmony and the creativity in the orchestration needed to compose interesting pieces with variety and colour, using so few instruments, was much more difficult to achieve. To ask pupils in Year 11 or 13 to write for a tiny group could be restricting, so we must, I feel, try and find a balance.

Positive reinforcement

I appreciate that I am in a very lucky position when going into school as a visitor. Before the lesson, the music teacher generously builds up this visitor as ‘a professional composer, coming in especially to work with you on composition’ etc., and I talk to the students and am listened to. I can see the pain on the class teacher’s face as I say something and all the attentive pupils nod and say, ‘yeah, that’s cool’ – when what’s being said is the same as the teacher has been telling them for the last four months.

Still, as we were told many times in our composition classes, ‘reinforcement by repetition is a good thing’.