The 2020 Covid-19 pandemic was a difficult and challenging time, which impacted all our lives. As we continue to reflect and take stock of our lived experiences during this period, many memories surface. Some of these, perhaps, reflect ways we found to cope, and others, perhaps more traumatic, include moments we would rather not recall. Understandably, for many of us, our emphases may have been on doing all we could to support friends and family, digesting the latest news, and understanding the guidelines we were asked to follow. But as distance increasingly builds between these moments and our current life experiences, opportunities for thinking about what the pandemic meant for aspects of our professional identities are also surfacing.

For the classroom music teacher, so many things about school learning experiences changed so quickly, and it was difficult to know if these moments were isolated, or if others were living through them too. Even more pressing is the thought that we may still be experiencing lasting impacts from this time, where classroom practices may have changed as a result. It is important to acknowledge some of these aspects, which may impact how teachers think about and ‘do’ music in schools, particularly as pre-Covid classroom musical learning may be becoming increasingly hazy in our consciousness.

Classroom music teaching in 2020

While there were research projects which considered musical contexts during the height of the pandemic, these tended to consider instrumental teaching, the challenges of performing in ensemble groups, and the significant impacts the pandemic was having on the lives of professional musicians. Although some studies do exist internationally, there were surprisingly few that considered the impacts on curriculum music in schools in England. This article discusses research based on one study that did take place, involving a survey of almost 60 music teachers from six regions in England, with follow-up online interviews with 12 participants. These surveys and interviews took place between November 2020 and June 2021, but the research continues to raise questions for reflection in 2024 and possibly beyond (Anderson, 2024).

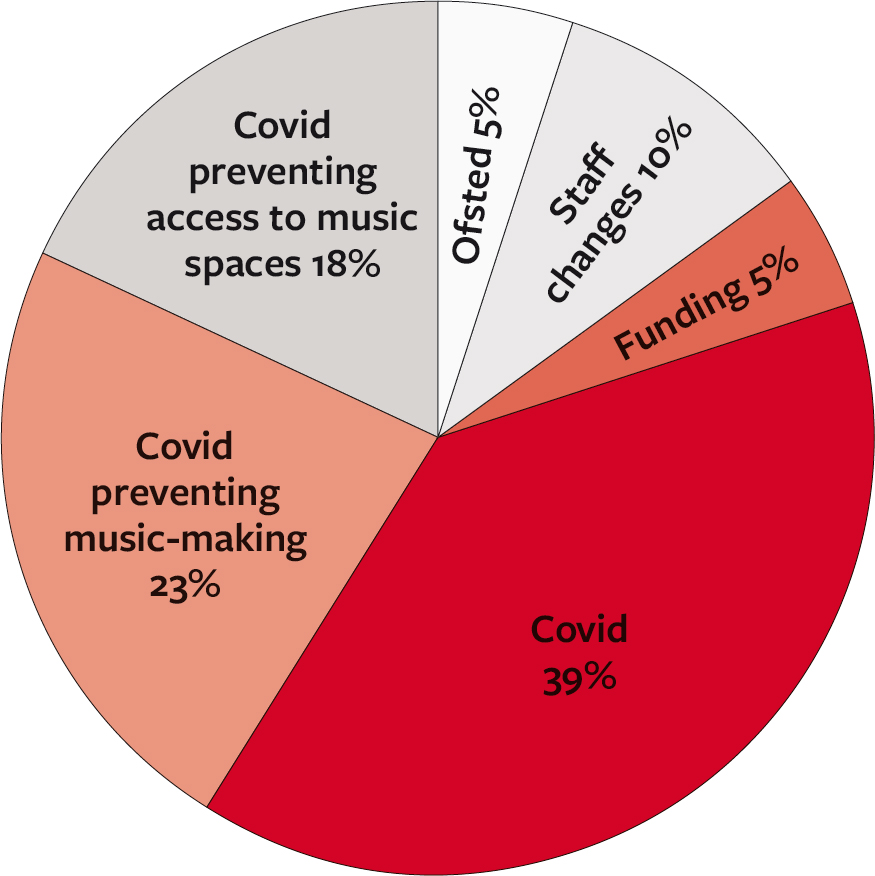

Although this research comes with the usual caveats about its limitations and those schools and teachers that are not included, it does, nevertheless, highlight some dynamics worthy of further thought. Many things are perhaps no surprise and were the experience of multiple classroom teachers. When music teachers were asked in the survey what had the most significant impact on their Key Stage 3 curriculum in 2020, perennial concerns were expressed, such as Ofsted and funding (5% of respondents cited both of these), with staff changes accounting for a further 10%.

As might be expected, a large proportion (39%) identified the Covid pandemic, but there were also a significant number of teachers who reported that school management responses to the pandemic impacted young people’s access to classroom music. In this vein, 23% of participants stated that Covid had impacted music-making, and 18% of music teachers said they no longer had access to music spaces in their school, following the return of in-person lessons. This is a generally unacknowledged difficulty, although Ofsted’s briefing notes series did discuss some of the challenges of wider school provision for what they termed ‘practical subjects’ (Ofsted, 2020), in which they included music.

‘Covid-safe’ practices

It therefore appears that in many schools, what were considered to be ‘Covid-safe’ practices presented music teachers with as many challenges as the existence of the pandemic. Such Covid-safe practices varied widely between schools. Some of the notable differences between those who participated in the research included: free use of classroom spaces and music keyboards around the classroom; music teachers who reported they were only permitted to use keyboards if they faced the same direction; comments that pupils were permitted to use practice rooms if the teacher did not enter the space; responses that described the use of practice rooms only where windows could be opened; teachers who told me that they were allowed to enter practice rooms and work with young people as normal; and teachers who stated that the use of practice rooms was prohibited during Covid times. These describe a wide range of different experiences teachers were told constituted ‘safe’ practices. Teachers also faced additional barriers with accommodation due to timetabling changes. This prohibited many of them from using music spaces and required them to teach in other areas of the school, such as science labs.

Music teaching during the pandemic

Music teachers are endlessly resourceful, and worked hard to enable musical experiences and development to take place, despite such difficult circumstances. However, the scenarios were challenging. As teachers talked about in the research interviews, it became evident that their usual pedagogical practices in music had been severely disrupted:

‘We’ve been teaching a class of 30 with 15 guitars in a French or History classroom and using a mat that doesn’t make a sound … I’m a firm believer in the chopstick. We each had a chopstick; we had a rhythm clock on the wall, and we’d do songs to it.’

‘There’s a lot of people panicking about what you’re going to do for seven more weeks sitting at desks. I don’t know what you do for music. Not much.’

Through circumstances, rather than choice, music teacher practices were transformed, so that teachers were no longer ‘teaching music musically’, as Keith Swanwick described it (Swanwick, 1999), but were compelled into teaching music in a way that could be described as ‘unmusical’. One teacher told me:

‘Teaching music musically has been very difficult, and it’s widened the gap: the kids who have instruments are going to do okay, the ones who don’t are going to get further behind.’

For the teachers who took part in my research conversations, music in the classroom looked and sounded very different during the pandemic. It was music-appreciation centred, rather than music-making and music-creating based; there were barriers to musical enrichment, as extracurricular opportunities were restricted or removed from school experience; and there was an inequity of access to musical opportunities as a result. Pupils found it challenging to collaborate following a prolonged period of learning from home, and music teachers were forced to re-define their philosophies of music teaching to align with the times. These were, needless to say, unintended consequences, but they were real problems nonetheless.

The factors classroom music teachers said influenced their Key Stage 3 curriculum the most between 2019 and 2020

The factors classroom music teachers said influenced their Key Stage 3 curriculum the most between 2019 and 2020

Present and future challenges

That was then, but what about now? We all know that Covid was challenging, and memories of how teaching was enacted at this time will continue to live with many of us. However, I can’t help but worry, just a little, at what may have changed as a result and continued unacknowledged in school learning practices. These aspects could have far-reaching impacts for music teaching. This is, of course, likely to be patchy and it’s rather tricky to make large-scale generalisations without more research with larger data sets. However, some of the changes which have emerged include different conceptualisations of curriculum, with longer and fewer lessons; the rise of online modalities (the parents’ evening is one of these where in-person events appear to be fewer); pupil access to school buildings during lunchtimes may continue to be restricted in some cases; and the way extra-curricular opportunities or musical experiences (such as concerts) are arranged may also present new challenges that were not part of the landscape before Covid.

It is worth pausing to consider if music education in schools has been transformed, and, as always, it is good to take time to reflect and think about these things and to consider what we want music education to be. With a curriculum assessment review currently underway by the new government administration, now is a valuable moment to talk about what gives music its distinctive characteristics and how to enable young people to have equitable access to music education in schools. Learning in music, rather than only about music, remains critical. It is up to us to ensure that music-making and creating remain central experiences for every child in every school.

Links and references

- Anderson, A. (2024) ‘Teaching music unmusically: the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on secondary school music curricula in England’. The Curriculum Journal, 35(3). tinyurl.com/mryv69y4

- Office for Standards in Education (2020). COVID-19 series: Briefing on schools, September 2020. Crown Copyright.

- Swanwick, K. (1999) Teaching Music Musically. Routledge.