Géza Szilvay teaching: ‘The violin is not the most natural thing to pick up and play … You have to shape the child's hands and fingers towards a comfortable and practical approach to the instrument’

‘I am always singing with the children – not speaking. I create and improvise so the approach is live music-making, not dull exercises.’ Here, in a nutshell, Géza Szilvay sums up his approach to teaching stringed instruments, which is embodied in his Colourstrings method.

We are sitting together at the Yehudi Menuhin School, which is hosting a Colourstrings International Training Course that Szilvay, at a sprightly 80 years old, is leading. Such is the success of his teaching method, it has taken off not only in Europe but in countries as far afield as South Africa, Australia, Korea and China. And so sure of its efficacy is Szilvay that he says: ‘I am convinced that I have developed a school that has everlasting value and will be taught after 200 or 300 years. I am not a missionary and I don't force it. It has its own value and speaks for itself.’

So how did all this come about?

A musical foundation

Géza Szilvay was born in Budapest in 1943 into a musical family, with his university professor father being an amateur cellist, and his older brother Csaba also a cellist. Szilvay recalls he must have been around five or six when he started to learn the violin. The two boys sang every day at school – but their childhood was not as idyllic as it sounds. ‘Life in 1950s communist Hungary was one of terror,’ he remembers, ‘and music/singing was, for us, a refuge.’

After the equivalent of A Levels, Géza went to the Bartók Conservatory and then the Liszt Academy, where he graduated in 1966 before completing a Master's degree (1970). Work came in the form of playing in the Budapest Symphony Orchestra as well as teaching violin and chamber music at Hungarian TV and the renowned Radio Children's Choir.

Moving to Finland

Performing with Csaba brought about a change of life when their quartet visited Helsinki, and the brothers were granted leave to stay in Finland for 18 months. Their leave of stay was extended, and the pair started teaching: ‘We were able to encourage and foster some wonderful players. We loved this, and so began the difficult process of staying in a foreign country. The Hungarian government took 12% of our income, but we didn't mind because we [had] received quality education in our beloved country. We stayed on in Finland because we enjoyed our work.’

Szilvay taught at, then became principal of, the East Helsinki Music Institute (one of approximately 100 music institutes, or musiikki opistot, in Finland). In 1998 he established a primary school offshoot where children could receive daily music education – an idea that has been presented at international symposiums since as a pattern for European countries.

The birth of Colourstrings

Back in the early 1970s, however, marriage was soon followed by the arrival of a baby. This proved to be a seminal moment in Szilvay's thinking: ‘Whenever I played the violin, our baby kicked in my wife's womb. I remembered that Kodály had said, “Music education begins nine months before the birth of the child.” [He later changed that to be “nine months before the birth of the mother.”] As an enthusiastic, expectant father, I began to think about our child-to-be's musical future and planned a way of teaching her for when she would be four or five years old; and I wrote the first book (43 pages) of what became Colourstrings Book A.’

Inspired by ‘colourful and magical’ children's books, Szilvay started to test out his ideas on his Finnish students. This proved so successful that Finnish radio and TV wanted to broadcast the approach. ‘I was doing two TV programmes for children each week. I must say that for music teachers the media have an enormous influence – as a result of the TV programmes everyone wanted to learn the violin and cello! We developed several orchestras, The Rascals, the Children's Orchestra, the Junior Orchestra, and then the Helsinki Strings.’ This string orchestra gained international renown, resulting in world tours and recordings of almost all the major string repertoire. Over the course of the next 45 years, Szilvay and his brother turned out more than 100 professional players and teachers.

‘I am lucky to have been able to work with my brother,’ he comments, ‘because without him these results would have been impossible. I use Suzuki's words when I say we “nurtured” hundreds of children.’

A child-centred approach

I ask Szilvay to summarise what is the unique selling point of Colourstrings. ‘This is almost an impossible thing to answer in one sentence! But I can say that this is the most child-centred approach there is, and my Colourstrings way of teaching [does not go] against any approach. Rather, I am filtering Kodály, Suzuki, Roland, and Orff together.’

Szilvay knows exactly what he is talking about, having met Zoltán Kodály, Paul Roland and Shinichi Suzuki – the last in 1984, after Colourstrings A and B had already been published. ‘I had the honour to drive Suzuki and his wife to their hotel, and I studied with him for that week. Suzuki had said he did not want to burden the child with the grammar of music before learning the violin. I told Suzuki that we encourage the children to be able to read before they start the instrument, which was the view that Kodály had instilled in us. I admired the success that I could witness in Suzuki, but I said we had a completely different approach. Now I quote Suzuki's answer: “Probably you have solved the problem.” That was such a wonderful endorsement and encouragement for my work.’

Being at one with the instrument

I mention that teachers I have spoken to on this week's training course say the playing style Szilvay encourages is one where the player is very comfortable and at one with the instrument. Can Szilvay elaborate on this?

‘The violin is not the most natural thing to pick up and play,’ he explains. ‘Holding the violin and the bow can feel terrible. You have to mould the child's hands to these, to shape the child's hands and fingers towards a very comfortable and practical approach to the instrument. Yes, this does mean touching the child's hands, fingers and arms, but there is nothing sinister in this at all. Sadly, there has been abuse, but this is not the way we work. A dentist has to touch a child's face and mouth, and a physiotherapist has to touch the muscles of the body.’

Left-hand pizzicato and harmonics

And what about left-hand pizzicato? ‘The violin has not changed much from Geminiani in over 200 years, except for the replacement of the gut strings with metal ones. I learned much from Suzuki and Roland. Roland taught left-hand pizzicato using just the fourth finger. I developed the idea of the so-called numbered pizzicato where, on the violin, the G string is plucked with first finger, the D string with the second finger, the A string with the third finger, and the E string with the fourth finger. The systematic use of the fingers to pluck the open strings (without the burden of intonation) will develop independent and dexterous fingers before the demanding stopping (intonation) movements.’ It is a remarkable innovation in string teaching.

‘Another new idea was the use of harmonics, which I also developed from Roland. Originally only the middle position was used, but I got the children to use natural harmonics in first position. It encouraged a lively bow-stroke movement and, of course, accurate finger positions, otherwise the harmonics would not work.’

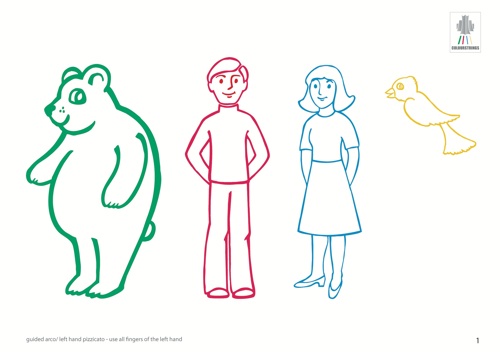

Illustration from Colourstrings Book A, relating to the four fingers and left-hand pizzicato

Illustration from Colourstrings Book A, relating to the four fingers and left-hand pizzicatoDeveloping talent

Szilvay has shared his work with both the American String Teachers Association and the European String Teachers Association (ESTA), demonstrating his work in Edinburgh at the Third International Conference. Violin professor Max Rostal, then chair and president of ESTA (which he co-founded), became a patron and offered his services to Szilvay in Helsinki for free.

‘Now it is my turn to repay,’ says Szilvay, ‘and I am the president of ESTA. I will help anyone who asks and will give free online courses.’

Of the many materials Szilvay has produced, he says: ‘The current approach is based on a violin tutor (A, B, C, D) which is child-centred, coloured and beautiful for the beginner up to about nine years old; but the material develops to that for college-level students, with several thousand pages of material including duos, trios, chamber music, orchestral pieces, concertinos and examples from over 200 years of music. I distilled studies from the likes of Dancla, Wohlfahrt, Kayser, Dont, Mazas and Feigerl. The tutor books are like a violin teacher's lexicon. The majority of other violin school's methods are quite fast, but Colourstrings is deliberately slow and thorough, enabling children of all abilities to develop their talent to the highest level they need. There are no gaps, everything is covered: for instance, all bowings like detaché, legato, martelé, marcato, staccato, flying staccato, spiccato, ricochet, sautillé and portato; and for the left hand, double-stops, artificial harmonics, fingered octave or even double trills. The genius of this foundation is that when students arrive at music college, they do not have to be taken apart.’

Supporting music education

As a country, Finland has clearly been supportive of arts education. I ask how Szilvay thinks we can persuade politicians to support the learning of music?

‘Definitely the secret is singing to begin with, because this is the first instrument – everyone has a voice. Kodály solved this problem. In Colourstrings, we “sing” on the violin. In Finland we were very fortunate with the media coverage of what we were doing, plus the long, dark evenings meant children were not so distracted! In our music primary school, children receive a singing lesson and an individual 45-minute instrumental lesson weekly. In addition, we were teaching in groups of about five to six children for 45 minutes every week. The East Helsinki Music Institute's music primary school instigated a review with children, parents and teachers, and the result revealed 98% satisfaction. Academic results were most encouraging and there was no bullying.

‘Music makes a difference.’