You've got twelve recorders, four guitars, one trumpet with a sticky valve, and an enthusiastic student who doesn't play an instrument. And Senior Leadership wants a Christmas concert in six weeks. Sounds like a nightmare? Worry not! With a little arranging knowhow, even the most challenging circumstances can be turned into a rewarding musical experience.

Core roles

No matter who you're writing for, ensure that your arrangement is complete, with all the core ‘roles’ covered. For most music, this means a melody; material that fleshes out the harmony; parts providing rhythmic structure; and a bassline. Avoid arranging long passages in which any of these core parts are missing, as this can make the piece sound bare.

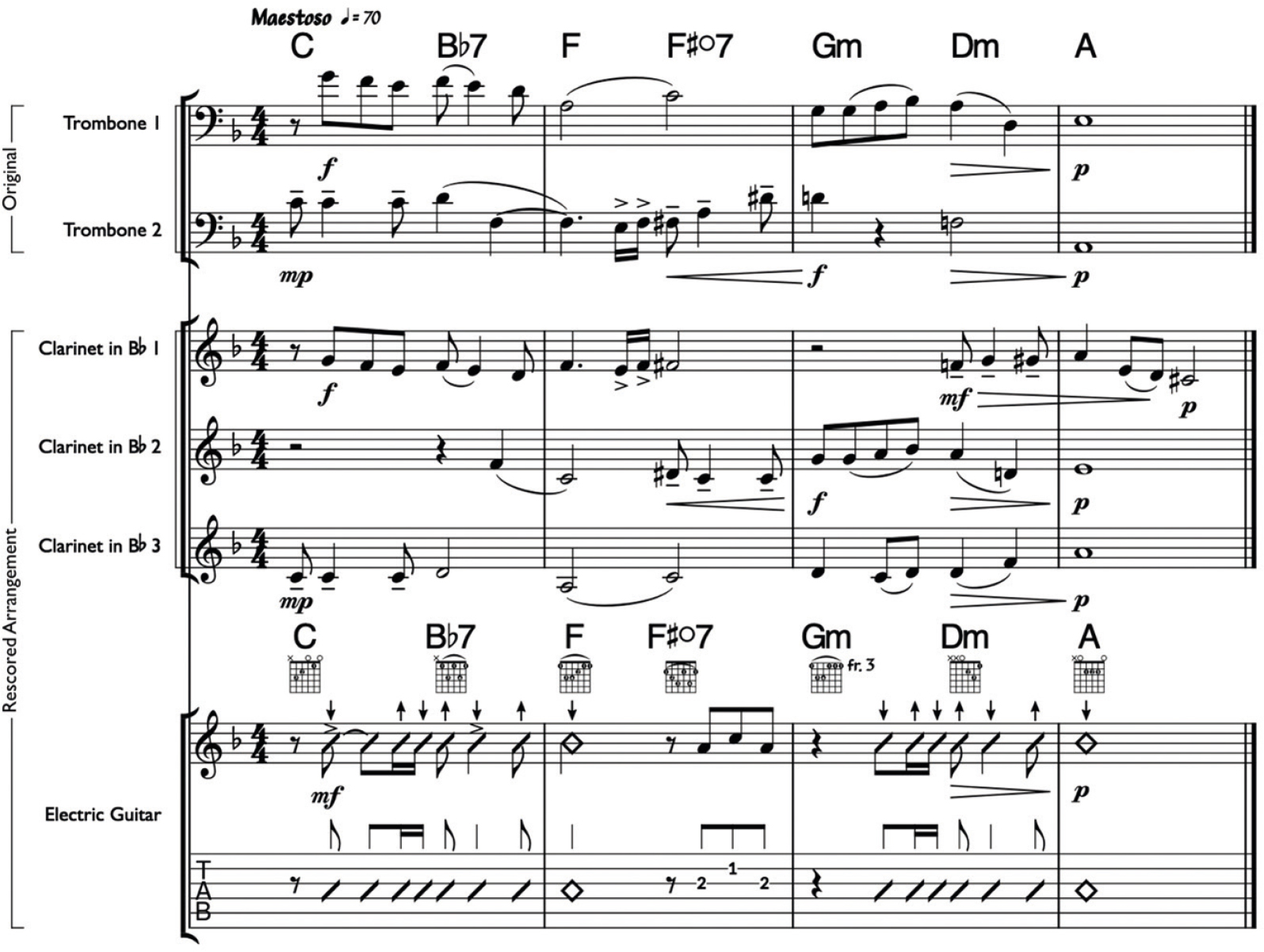

In Figure 1, note how the melody, harmony, bassline and rhythmic structure (of moving quavers) are all present. Also note the constant rhythmic motion: when the melody is still, the bassline gets to shine in the role of a countermelody.

Figure 1. Menken: A Whole New World, arr. J.B. (©1992 Wonderland Music Co. & Walt Disney Music Co.)

Figure 1. Menken: A Whole New World, arr. J.B. (©1992 Wonderland Music Co. & Walt Disney Music Co.)

Musical satisfaction

Share each musical role among your ensemble members, and keep things interesting; for example, avoid having cellos play repetitive long notes beneath the melody.

Give accompaniment figures rhythmic energy, even in elementary parts. Remember that rhythms which are challenging to read are often easier if learned aurally.

In Figure 2, notice how the bassoon part fulfils a melodic role for the first two bars before switching to a supporting and harmonic accompaniment figure. Players of all ages and abilities often cherish even the briefest moment to shine.

Figure 2. Dammers: Ghost Town, arr. J.B. (Orchestras for All). (©1981 Plangent Visions Music Ltd.)

Figure 2. Dammers: Ghost Town, arr. J.B. (Orchestras for All). (©1981 Plangent Visions Music Ltd.)

My advice is to make every part musically satisfying. The single most effective way to do this is to sing everything, every individual part – if it's difficult to sing or (worse) very dull, see if you can change that. In the next example, in Figure 3, a very dull trombone part (bars 21 to 30) contrasts with one that is not much more challenging, in a technical sense (bars 57ff), but is far more satisfying to play. It also provides an opportunity to get into dynamics and articulations.

Figure 3. Trombone part (example) by J.B.

Figure 3. Trombone part (example) by J.B.

A common mistake is to oversimplify a well-known melody when arranging. In a quest to make this easier to play, we might take the rhythmic heart out of a tune; but this isn't satisfying to play or listen to, and might even be confusing! Try to keep well-known melodies as they originally sound, even if this makes them look more challenging. You'll be amazed at the level of accuracy you can achieve in rehearsals.

Adapting existing arrangements

You may have an existing arrangement but it's not quite doing the job. You can produce altered or additional parts to accommodate particular needs, or include instruments not in the original score, but this might alter the overall balance. Consider, therefore, the effectiveness of the arrangement as a whole, as well as the needs of individuals. You may find that you have to alter multiple parts to ensure a balanced arrangement.

If you have a big concert band with 11 clarinets but no trombones, and you need to incorporate some guitarists who don't read stave notation, start by looking at the roles the original trombone parts took (e.g. a few bars of melody, and sections of ‘harmonic middle’). Then, work out where you can redistribute these missing roles across the players that you do have.

For example, extra clarinets could play the melodic parts and some harmonic material, as in Figure 4, and harmonic parts could be written into a straightforward chord-sheet for the guitarists. (Some software packages offer handy tools to create special notations like TAB and chord diagrams automatically, or without too much extra effort.) Your guitarists could enhance the rhythmic structure with a strumming or picking pattern. Consider the roles and intended sound; you don't have to be an expert in the technique of every instrument to get these across.

Figure 4. Reworked score, by J.B. (©2024 James Brady)

Figure 4. Reworked score, by J.B. (©2024 James Brady)

Adding a new part may not alter the overall balance materially. As before, just ensure it is sufficiently engaging and satisfying to play.

Starting from scratch

Sometimes our needs go beyond adaptation. When arranging from scratch, you get to involve every member of the ensemble exactly as you wish, including yourself! This may seem daunting, but needn't be overwhelming.

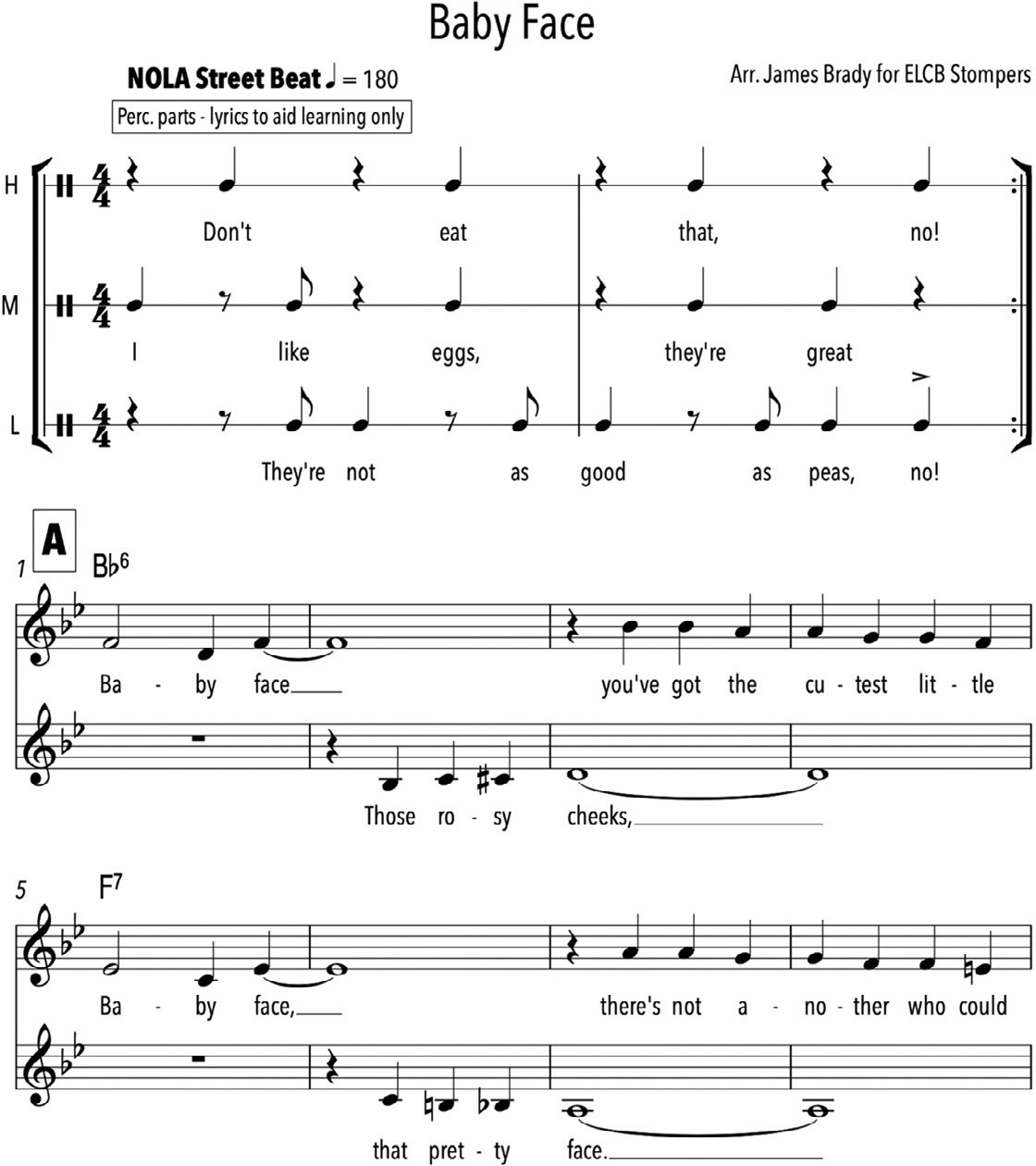

In Figure 5, we have part of a very simple arrangement for a mixed-age, mixed-instrument and mixed-ability ensemble. The three rhythmic parts at the top can be mapped onto percussion instruments to create rhythmic accompaniment for the melody and countermelody. When singing these rhythms, the lyrics aid aural learning and memorisation.

Figure 5. Akst and Davis: Baby Face, arr. J.B.

Figure 5. Akst and Davis: Baby Face, arr. J.B.

Co-writing

Normally, you have a chance to reconsider what an arrangement needs to be and who the arranger is. If you can work with the ensemble first, instead of planning to fix every aspect of an arrangement before the first rehearsal, create just enough material (as in Baby Face, Figure 5) to involve everyone in the ensemble in the music-making. Then, start making decisions about how to develop the arrangement together. This is a wonderful way to build a sense of ownership among your ensemble members and seek out budding composers!

Out of the box

Need something right at the start of term that will work immediately? Notation is often the means for this. In addition, you may be arranging without knowing the abilities of specific players, therefore consider providing an array of options that players can select from according to individual experience and levels of confidence.

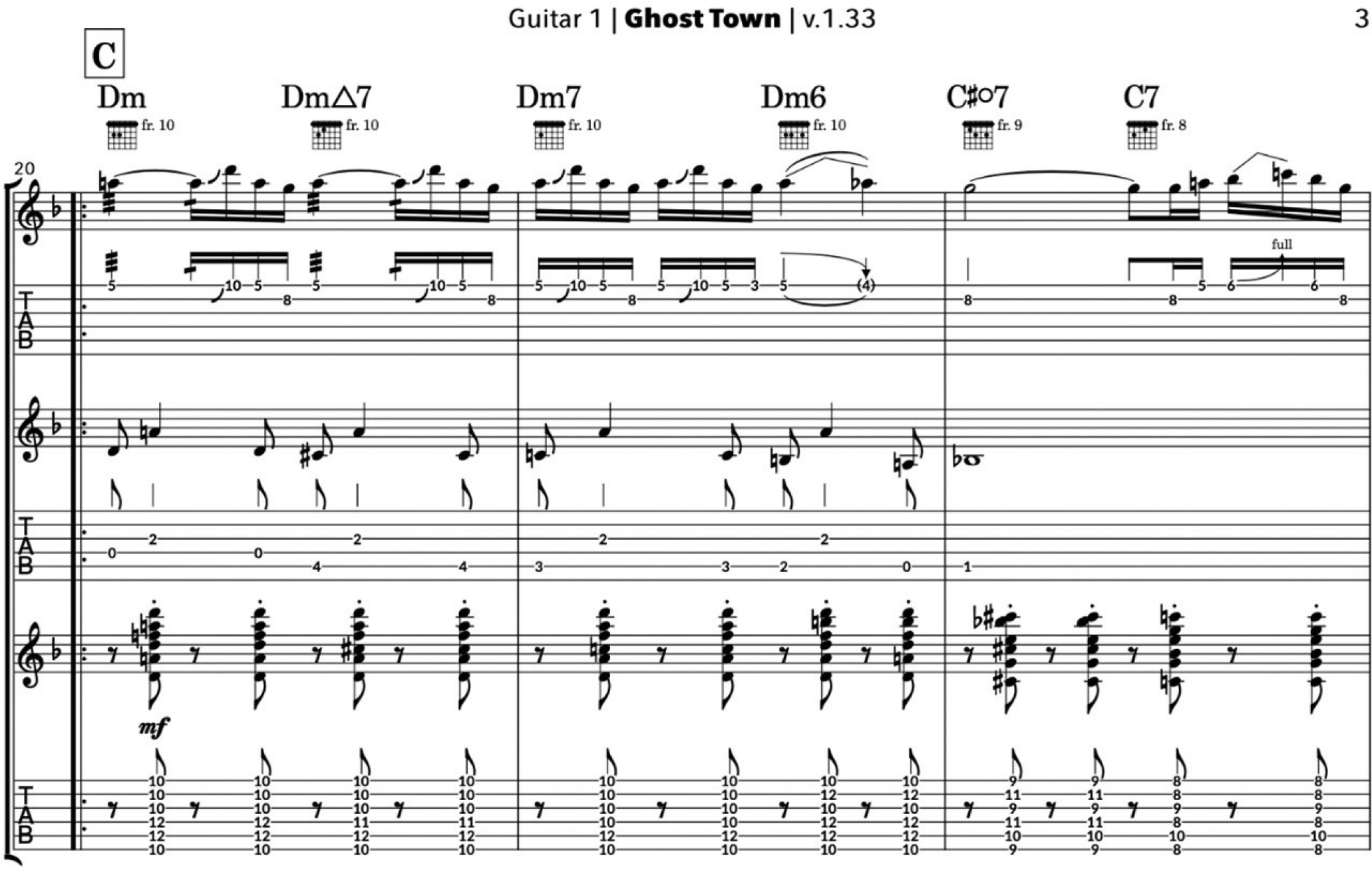

In Figure 6, a single part contains options for the guitarist. Three distinct routes are offered, each in stave then TAB notation, comprising a lead option, a much simpler single-note option, and then a chordal-shape option, accommodating widely differing approaches to guitar technique.

Figure 6. Dammers: Ghost Town, arr. J.B. (©1981 Plangent Visions Music Ltd.)

Figure 6. Dammers: Ghost Town, arr. J.B. (©1981 Plangent Visions Music Ltd.)

Beyond the dots

Consider the following tools that avoid stave notation and may speed up the learning process:

By rote. Start working with a new ensemble by teaching them a few simple parts by ear and then developing a non-notated piece in collaboration. Quite sophisticated arrangements can be created ‘live’ in rehearsal (or even performance!) through call-and-response, repetition and gradual variation. This also helps your ensemble develop musicianship skills.

Backing-tracks. Practice- or backing-tracks can be easily exported from most notation software packages (though remember to insert a count-in) and can really help with independent practice. If you have the resources, why not incorporate additional digital instruments or soundscapes into your performances? You may find that there are students or ensemble members already highly active in music production who could contribute massively in this way, even if they lack instrumental skills.

Short hand. Some instruments have other options when it comes to notation, such as TAB, drum notation or chord symbols. If you're going to be arranging for these instruments, don't be afraid of what you don't know; ask a colleague for help or look online, or seek out one of the many good books on arranging. Notation software is also a safe place to experiment.

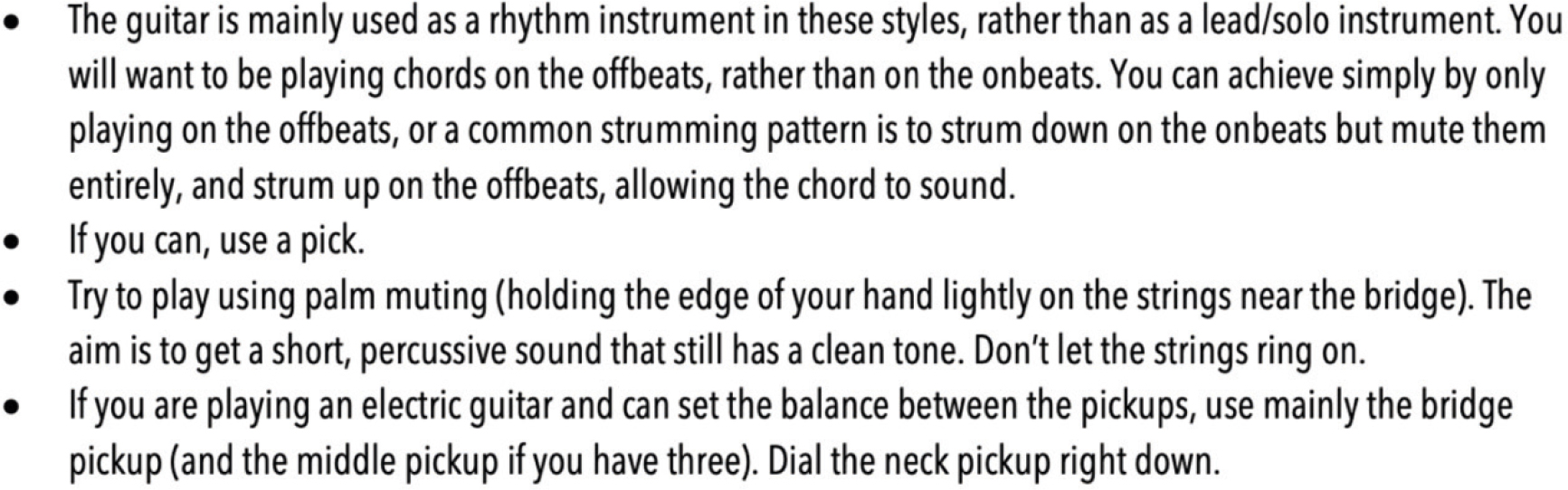

Written instructions. A written rubric can take the place of notation, and provide valuable information that isn't easily encapsulated on a stave. Take, for example, the advice in Figure 7 (next page) on how to get the right sound for Two-tone, Ska, Reggae and other popular Jamaican or UK-Jamaican styles. The rubric is from a guitar part in an arrangement of ‘Ghost Town’ by the Specials. Note the nonjudgemental, empowering tone of the language: ‘If you can’ rather than ‘you should’, for example.

Figure 7. Introduction to Ghost Town (arr. J.B.)

Figure 7. Introduction to Ghost Town (arr. J.B.)

Thinking beyond the notes

Utilise the diversity of your ensemble. When your ensemble has a wide range of abilities, it's easy to fall into the trap of being overly reliant on the most able. All players can contribute meaningfully through non-instrumental means such as singing, body percussion, movement, discussion of repertoire choice or even costume design. Try to adopt a mindset focused on creating performances with whomever your ensemble includes, rather than trying to fit into a pre-existing mould.

Approach repertoire with enthusiasm and ambition. If you consider a technically challenging piece to be a series of hurdles to overcome, that will be communicated to your ensemble in the form of apprehension. If you are too conservative in your choices, you risk boredom and miss opportunities for growth. Bringing enthusiasm for every part of the arrangement, down to the simplest part, will provide a positive model for your ensemble and encourage ownership and commitment.

Remember the wider social purpose of ensemble music-making in building bonds between age groups and communities. For example, the multi-generational practice of Brazilian samba schools and Zimbabwean marimba ensembles embody social and cultural purpose beyond musical performance – a practice we sometimes forget in the UK. Remember, too, that music is an activity first, a sound second; and only after that is it a set of symbols.