‘There are musicians, and there are singers’, according to the saying. We may cringe at such a statement, but many singers have had a different route into music. They have sung from toddlerhood without analysing what they are doing, like we learn our native tongue. They are as confused by being asked to analyse their musical actions as the average English speaker who is asked to describe the use of the subjunctive.

Along with their aptitude for their instrument, singers have another issue that mitigates against the ability to sightsing: voice placing and production. For high notes you have to dig low, and for low notes, hold up high. I came to singing late, having trained as a pianist and violinist, and found this to be a complete revelation. Some professional singers operate without having reading skills, particularly in the area of popular music, but in order to qualify as a teacher they are usually expected to jump through this hoop.

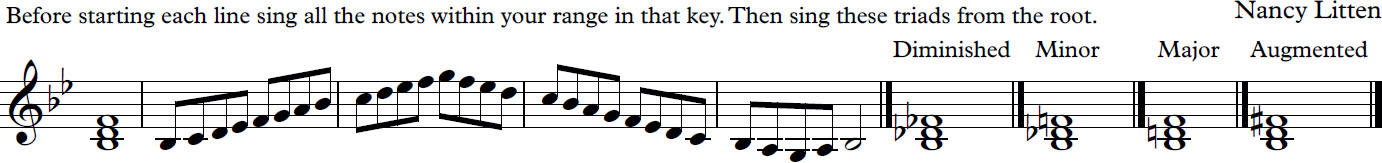

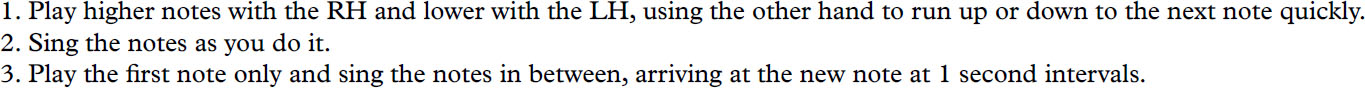

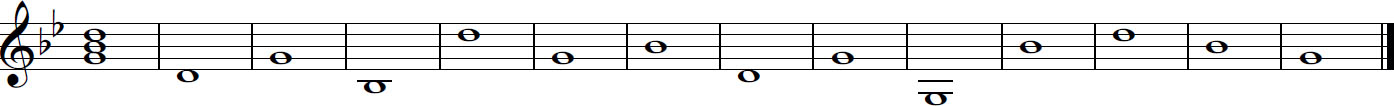

I have come to the conclusion that the most important thing to develop is a sense of key, and the ability to differentiate between tones and semitones. Scales can be sung without thinking, which is why in my recent book, scales often begin on notes other than the tonic. The difference between scales and arpeggios also needs to be grasped. Singers often confuse 3rds and 2nds, as they have been taught to sing triad notes as warm-ups, so they seem as natural as scales. Once semitones, tones and minor/major 3rds are secure, 4ths and 5ths are less of a problem. One secret is to hum the notes in between, and part of the practice is to do so in key; that way a diminished 5th is observed, rather than sung as a perfect 5th. The ‘hummed’ notes need to be fast and rhythmic (normally on the final semiquavers or demisemiquavers of the beat). So for a 3rd there is one note to hum, two for a 4th, three for a 5th, four for a 6th, while 7ths can be accessed from the octave. I use ‘One Second Wonders’ (Figures 1, 1a and 2).

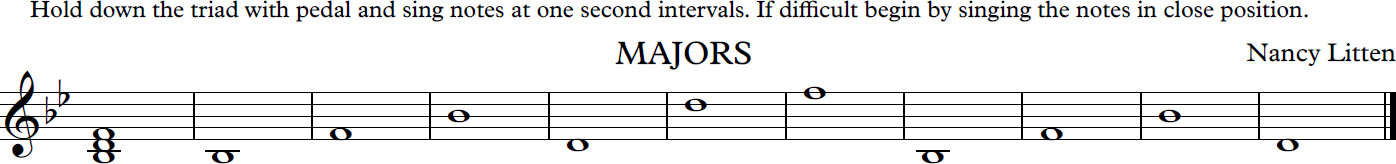

For minor scales I encourage the melodic form, as this is used in songs (mostly sharpened 6th and 7th going up and according to key signature coming down.)

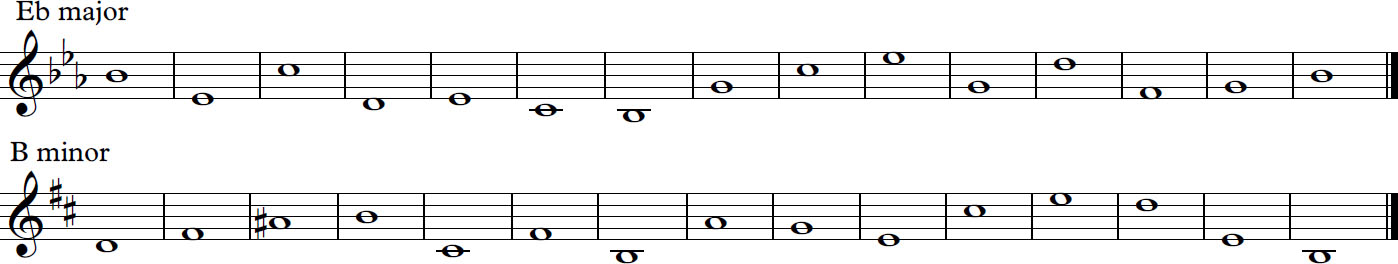

Another vital skill is being able to recollect the keynote at any point in the song and relate other notes to it. The minor keys are usually harder than the majors (Figures 3 and 4).

In my book, lyrics are added. While not compulsory, I find that they help novice sight-singers to follow the music and become aware of the rhythms. There is plenty of mileage in tapping the main beats while singing – crotchets in simple time and dotted crotchets in compound.

The book's second strand addresses an area where many pianists feel less than confident: keyboard harmony, and in particular, accompanying songs from chord symbols. Starting with primary chords and suggested realisations, it moves into more complicated harmonies as the singer's reading progresses. There are exercises for the pianist at the start of each chapter to ‘bed in’ the new chords and inversions. It is a joint learning experience where neither the singer nor the instrumentalist can feel superior.

Figure 1 ONE SECOND WONDERS

Figure 1a

Figure 2

Figure 3 ONE SECOND TRIAD NOTES

Figure 4 MINORS

Nancy Litten's Choral and Vocal Sight Singing and Keyboard Harmony books are published by Alfred: Pianist Edition (20172UK) at £12.95; Singer Edition (20173UK) at £9.95