I start by asking where Harris' calling as a musician came from. He describes how, at the age of six, he acquired a grand piano in his bedroom without much explanation from his parents. They weren't musical, he says, and neither were there role models within the family. His father, a ‘hard-nosed businessman’, would probably have preferred him to follow a more worldly career. But the piano stayed and, in spite of Harris' liking for doodling rather than ‘proper practice’, he was supported. Some of his earliest compositions date from this doodling period.

His formative years as a musician came while attending Haberdashers' Boys' School in Hertfordshire. During his first concert at ‘Habs’, as a member of the school choral society, he sang Britten's Rejoice in the Lamb and Kodály's Te Deum. He enjoyed the experience so much he set his heart on a career in music. He joined the school's ‘amazing’ orchestra as soon as he could, and was soon playing Dvořák's ‘New World’.

Importance of having a good teacher

Harris is the first to acknowledge the impact teachers had on his career. He speaks fondly of the staff at Habs and in particular an exceptional clarinet teacher, John Davies, under whom he later studied at the Royal Academy of Music. Davies taught at the RAM for over 40 years, nurturing clarinettists who became international artists. But he understood how education was all ‘about drawing out, not putting in’ and building inner confidence – themes Harris would return to in his own teaching. Davies encouraged students to think broadly and encouraged him to pursue teaching as a main pathway. They became firm friends and collaborated as editors on publications such as 80 Graded Studies for wind instruments.

While at the RAM, Harris also studied composition and conducting. But after leaving, he attended the Institute of Education at the University of London. For a potential music educator in the late 1970s, there were few better places to be: Harris was a student of Keith Swanwick, among others, the leading researcher and thinker behind some of today's music education philosophy.

How significant was this? ‘I was lucky enough to have Keith as my tutor’, Harris says, ‘when he began writing his seminal books A Basis for Music Education and Music, Mind and Education. I found this all deeply thought-provoking.’ As with Davies, the two kept in touch.

Being a teacher

Fast forward to the 2020s and we find Harris teaching music education at the RAM, being a visiting professor at the Danish Conservatoire in Odense, offering a variety of workshops and delivering INSET courses. This scope means he has contact with a wide range of teachers. What's the advice he most often gives? ‘Be kind, be as unconditional as possible, and try to find the right route for each pupil’, he says. This positivity and empathy with players runs throughout his teaching and writing.

Our discussion moves to instrumental group-teaching in schools. Harris has followed closely the development of Wider Opportunities, First Access and similar formats. ‘Giving all children an opportunity to play a musical instrument is naturally a wonderful idea’, he suggests. ‘A good number have really benefited. But there have also been problems. Without going into great detail, I would still recommend the use of that old stalwart the recorder as a start-up instrument. It has many advantages over more sophisticated instruments; among them, being able to make a decent sound immediately, not breaking when it's dropped, and not requiring tuning. Group teaching can be very effective, but it does need thoughtful managing.’

Continuing the subject of school music, I ask what changes he'd like to see over the coming years. ‘It would be wonderful if we were able to go back to offering free tuition to those who desire to learn to play an instrument or sing’. This stems from a firm belief that music education should be available to all. He would also like to see specialist music teachers in state primary schools, where the journey for young musicians often begins.

With regards to one-to-one teaching, I'm aware that Harris has a number of private clarinet students from elementary level to post-diploma; they're taught online as well as in-person. Having researched specialist music education for highly talented players (as was the case with Julian Bliss), Harris has taken this experience with him to institutions around the globe. Are there significant differences in how to approach young virtuosos, I ask? ‘Yes. There are still some places where music teaching, especially at higher levels, is – not to mince my words – rather brutal, mostly in relation to technical work. This begs some fundamental questions such as do we need to be brutal to reach these standards?’

Educational author

Harris has published many educational titles, from collections of classical repertoire (sometimes in simplified versions) to series on sight-reading, scales and more. When asked to single out titles he's most proud of, he describes Unconditional Teaching (2021) as an important read in current times. The book received critical acclaim and was reviewed in Music Teacher (March 2022); but, essentially, it explores the environment of lessons and the pre-conditions teachers carry. It encourages teachers to identify their requirements (or ‘conditions’) early on and manage these in the interests of maintaining a two-way flow between teacher and student.

Unconditional Teaching is timely because, ‘Maybe for the first time in the history of education, we are having to fight for our survival. Being unconditional will help in a big way – we must continually move forward in a positive and productive way. So being unconditional helps us remove, or at least manage, anything that might block our journey and our pupils' journey’.

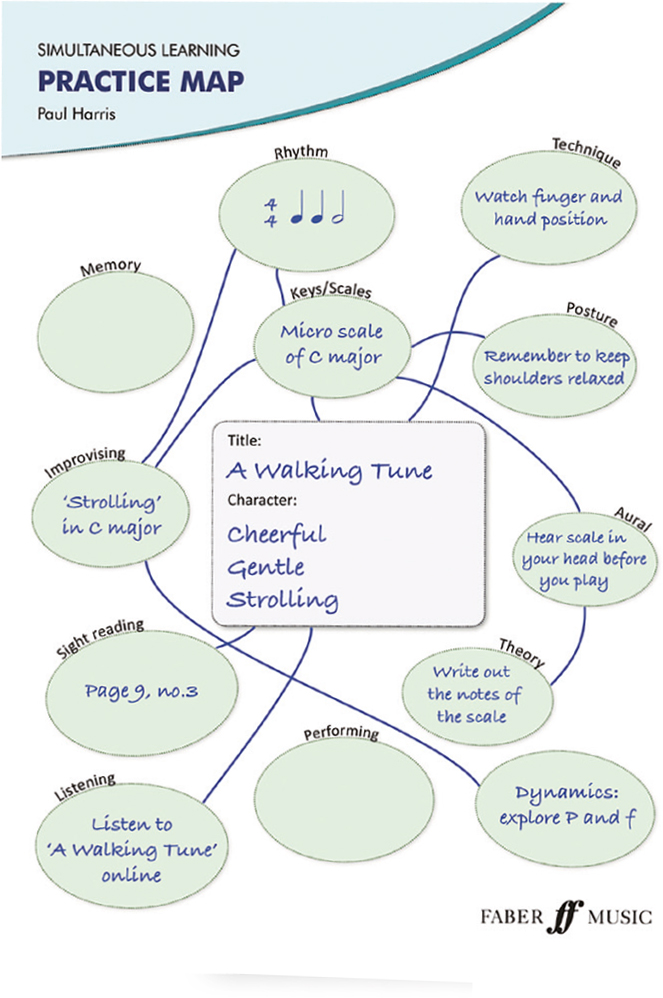

Of the other books, readers have written to the author about The Virtuoso Teacher and Simultaneous Learning, suggesting these have helped define a style of teaching, which Harris finds very satisfying. Simultaneous Learning is now a widely accepted approach, blending skills and types of activities in an imaginative and holistic way, and encouraging students to learn independently. Unconditional, The Virtuoso and Simultaneous are also in demand as a themed suite of workshops.

When looking more broadly at Harris' activities, it's tempting, I suggest, to see several symbiotic relationships. ‘Yes, definitely’, he says. ‘One of the main principles of Simultaneous Learning is that everything connects, which, if you look carefully enough, it does; so making connections between the various areas begins to become instinctive.’

For future projects, Harris is ‘working on more approaches to reading and sight-reading – if we can't read music, its future has to be in question’.

Biographer-composer-performer

In education circles, few are aware of Harris' (coauthored) biographies of Sir Malcolm Arnold, Malcolm Williamson and Sir Richard Rodney Bennett. The music of these three composers he particularly likes, but with the first, the connection runs deeper. Harris has long championed the works of Arnold (1921–2006), one of the most underrated British composers in his opinion. Arnold's fate was sealed as a ‘melody-led’ composer, Harris argues, during an era of modernist orthodoxy. This October, in Northampton, Harris will be organising the 18th annual Malcolm Arnold Festival, a festival he's proud to have founded.

As a composer of concert works, Harris is responsible for seven concertos. Five of these, the ‘Buckingham Concertos’, were written for students at Stowe School, where he worked. ‘One day’, he says, ‘I'd like to write a sixth Buckingham concerto, for violin and cello.’

As a professional clarinettist, Harris recently performed the Mozart Clarinet Quintet, the Krommer Double Concerto and is currently preparing the Malcolm Arnold concerto. In 2022, his lifelong experience of playing as well as teaching the instrument culminated in The Clarinet, a 230-page lockdown project that's a guide ‘to every facet of playing the clarinet’.

Courtesy Faber Music

Courtesy Faber Music

Publisher-philanthropist

In 1995 Harris established Queen's Temple Publications to make ‘interesting and useful wind chamber music’ available. QTP has since expanded to include other instruments and choral music, and has works by James Rae, Iain Hamilton, Charles Camilleri, Timothy Bowers and John Dankworth among others. It also carries the much cherished Wind Quintet Op. 2 by Sir Malcolm Arnold.

For younger musicians, Harris also runs a small Foundation. ‘I established this to help young musicians fulfill a particular ambition that will help further their musical studies and deepen their love of music.’ Every six weeks or so, awards of up to £100 are made to players in full-time education and aged between 12 and 16. He sees this as giving something back. It also speaks to his approach of being kind and unconditional.

fabermusic.com/we-represent/paul-harris