The back-to-school collywobbles – everyone gets them. In fact, our brains are designed that way: the amygdala seems to interpret change as a threat and prepares our system for fight or flight, and this adrenaline rush can cause both excitement and fear. So, with the excitement of a new term comes trepidation – most teachers report at least a slight dip in confidence. Are our teaching chops still up to scratch? Will I still be able to engage children and remember what was once second nature to me? Be reassured that you’ll soon get back into the swing of things, within a few hours/days/weeks, but it's good to be prepared.

While very much a primary specialist, I have worked in a range of settings in the last 20 years: EYFS, primary, secondary, A Level, adult; and one-to-one or classes of 60. So, what follows are strategies that I have found useful in overcoming general teething problems we face. Whatever setting you are in, whatever curriculum you follow, it's worth establishing good practice before even thinking about what's to be learnt or achieved. There is no point in teaching solfa to a class, for example, if everybody is singing a different ‘do re mi fa sol’ with poor pitching, or teaching the concepts of rhythm and pulse to a class who can't feel or hear these in the music. Establish decent unison singing first, before rounds, canons and part-singing.

1. Set up routines, atmosphere and expectations

The atmosphere and expectations we set up in September will set the tone for the rest of the year. Now is the time to establish a safe space, where all contributions are welcomed and valued, and to establish routines.

If you are a primary class teacher, I would recommend the little-and-often approach, singing at least 2–3 times per week. If you are a specialist teacher seeing a class once a week, do everything you can to get children singing in between your sessions; this will make the world of difference, especially to pitching and pitch-memory. Musical routines such as tidying-up songs or lining-up songs, as well signals – stand up, make a circle and so forth – will help normalise singing in class and help with behaviour management. Enlist the help of class teachers and TAs.

Consider the space you are working in, and how it is being used. What are the possibilities for movement and formations such as circles? Is there a better space in school that you can use? Is the weather nice enough to take the children outside to sing?

What messages are other staff (adults) giving out? If a TA is getting on with paperwork or a support worker is refusing to support a child in their music-making, you have grounds to challenge this. I have banned all such practices: if you are in the room, you are making music!

2. Engage the class

For those reluctant children, TAs, teachers(!) and so forth, I find a few things work wonders with people of all ages, namely:

- Give them opportunities to include the music that they listen to. You might do a game with pulse movements to a piece of music of their choice, or tap the pulse along on your desk as you listen. What gets children singing along?

- Give them something to focus on. This may be an engaging Kodály game or Dalcroze movement activity. Chiffon scarves may alienate children of a certain age who see it as childish, but for everyone else, including adults, such props can overcome self-consciousness. Parachute and ball-passing games are great for getting everyone involved and singing and moving musically, forcing their focus elsewhere – away from themselves or their voice.

- Don't make any judgements about their music at this stage: all expression is good, even shouting and silly noises; especially silly noises, in fact, where we can express a range of timbres, pitches and rhythms.

- Let them not participate, if they wish, at least initially. ASD children may be overwhelmed by the social singing-games of Kodály. Others may want to listen and absorb what's going on, and get a clear idea of the sound in their head from repeated listening before trying to replicate what they hear. This is a very good thing. Encourage participation but never cajole or coerce. They will generally join in when they are ready, so be patient.

- Encourage your singers with a lot of songs and games. I recommend Lucinda Geoghegan's Singing Games and Rhymes series, published by NYCOS. Encourage a bit of silliness. From elsewhere, games like ‘Peter Taps’ and ‘Rubber Chicken’ are ideal early games, as the outcomes are so daft that it's hard to feel self-conscious afterwards!

3. Don't ask the impossible

In primaries, I often see children being pushed to sing notes that they can't physically sing – because the smaller (and higher) average vocal-range of younger children has not been considered. Start with simple early songs with a fairly narrow range that everyone will be able to sing successfully. For those teachers new to singing, make sure you are singing at a pitch that is best for the class, not for your own voice; because younger children engage the ‘head voice’ – higher than your speaking voice – to get the best sound.

4. Establish focus and attention

Concentration like this, especially for younger or SEND children, is also cognitively demanding and difficult to sustain; so it should be used wisely, with opportunities for relaxation and play activities requiring more diffuse focus. At this early stage, here are some ways of focusing attention while you present a new song or rhyme to younger children. These also stop songs becoming boring and repetitive, despite you repeating them over and over.

- Ask children to focus on the actions while you sing.

- Have the puppet sing a song.

- Ask children to play an imaginary instrument along with you.

- Get children to join in with a refrain.

- Present actions as a pulse.

- Miss out key rhyming words when repeating the rhyme.

5. Engage in copycat singing

For this, use a simple song like ‘Copycat’ or ‘Hey, Hey’. For older groups, any song with a simple refrain or call-and-response (e.g. ‘Step Back, Baby’) will work nicely.

Adopt clear signals for indicating when pupils should be singing and when they should be listening carefully. Simply gesture towards yourself when you want to sing, and towards the children when you want them to sing. You will have to go through a period of establishing this, patiently, and it is important that all staff in the room give children the same focus and respect when they are singing.

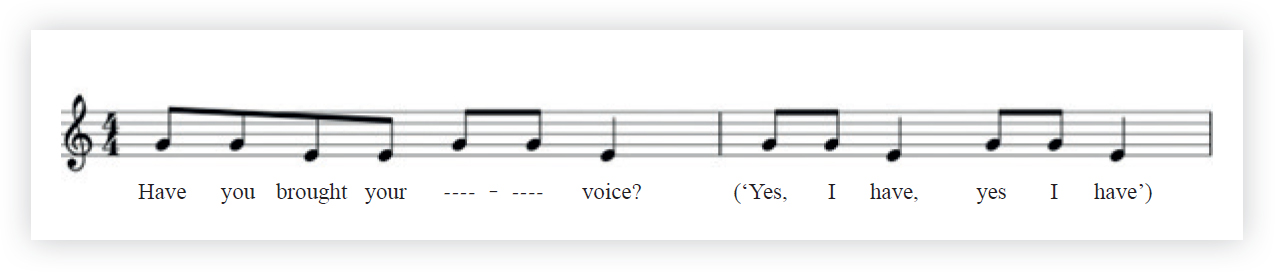

‘Have you brought your … voice?’ is a great way of introducing vocal experimentation for most ages. Use ‘high’ or ‘low’, ‘fast’ or ‘slow’; emotions ‘sad’, ‘happy’ or ‘angry’; and as many animals as you can imagine (‘pig’, ‘dog’, ‘cow’, ‘emu’, ‘unicorn’). Try to use as wide a range of timbres, pitches and dynamics as you can. Including an element of movement is essential – just ask a Dalcroze teacher.

If you can subtly change your pitch, this is a great way of focusing the class's tuning and listening. Encourage children to match everything about the ‘call’, including subtle changes of pitch.

6. Warm up the voice and body, and consider posture

A good warm-up can make all the difference. For best results, stand with your feet a shoulders’ width apart, knees unlocked and bodies relaxed (I often see bodies tensing up into ‘good singing posture’, so we need to be wary of this, too). There are many ways to warm up the voice and body, but, with lesson time at a premium, here's a 5-minute warm-up which works nicely:

- While in a circle (ideally), engage in a simple song with movements which encourage shaking, stretching and loosening up the limbs.

- Ask pupils to move their shoulders as far forward as they can; then up as far as they can; and then back. Then relax the shoulders.

- Warm up the face. Ask pupils to eat spaghetti (small round mouth); a whole watermelon in one bite (large open mouth); a (vertical) pencil (narrow mouth, open wide); and a (horizontal) slice of bread (mouth fairly closed but wide).

- Ask children to put their hands on their tummies and give a single loud laugh (‘Ha!’).

- Do some sirening (sliding up and down between pitches) using sounds which create resistance – ‘j-j-j’, ‘v-v-v’ (with small round lips) – or even while blowing raspberries, or singing through a straw into bubbles. Go from as-high-as-you-can to as-low-as-you-can, and back up. This opens up the vocal folds and explores the vocal range. Is the tummy still moving similar to when we laughed?

- Sing the same song/game, with some of the resistant sounds: ‘j-j-j’, ‘v-v-v’ and so on. Sing it again with the ‘laughing’ diaphragm movement. You should notice an improvement when you sing the song normally.

Final thoughts

This is by no means a comprehensive or exhaustive methodology for starting to sing with new classes or choirs. But, hopefully, some of these strategies will be useful to some of you, some of the time.

Good luck with getting back to the best job in the world: teaching music. Let me know how you get on at @musicedu4all on Twitter!