Does singing tone really exist on the piano? Does it make any difference whether a piano key is hit by a finger, fist, or an umbrella? This is a question posed in the piano edition of the Yehudi Menuhin Music Guides (1976) by Louis Kentner. The question is seemingly valid. The piano, at first inspection, is undeniably percussive; filled with dozens of little hammers busily striking strings. It seems impossible that such an instrument could produce anything but percussive sounds.

However, many pianists and piano makers would take issue with the idea that the piano cannot produce a singing tone. In fact, C. Bechstein confidently boasts of the singing tone of their pianos, and the pianist András Schiff praises Bechstein for their ability to build pianos that sound like ‘little birds’. The question, then, is not whether singing tone exists on the piano. The question is, does singing tone exist within the player? If not, why? And how can we teach it?

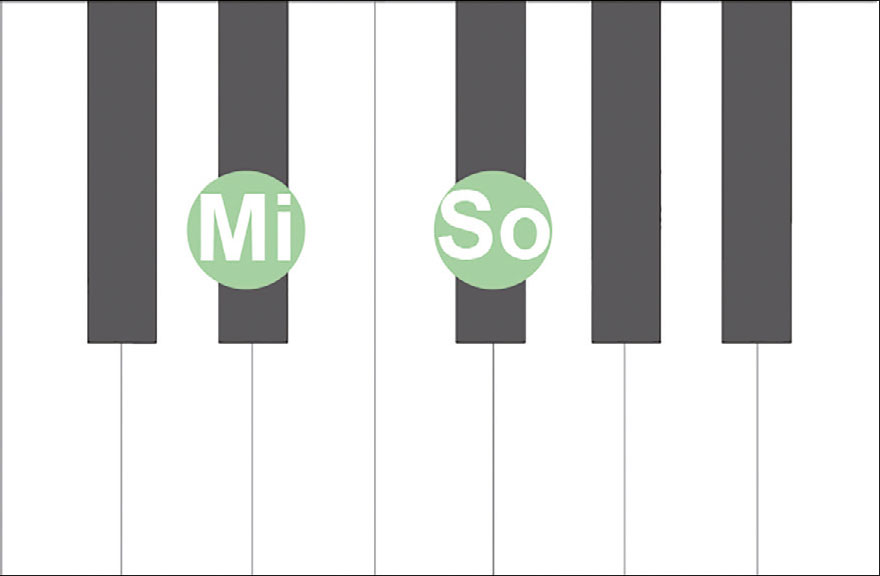

Graphic 1: So-Mi, B major

Graphic 1: So-Mi, B major

Movable do

When presented with the subject of ‘general music education’, we automatically think of singing. When children learn music in groups they typically do so through singing. The 19th-century teacher Sarah Glover pioneered a method of teaching children to sing using her system called the Norwich Sol-fa System. Through this method children learned to sing together using ‘moveable do solfège’. The method was impressive enough that her contemporary John Curwen adopted her principles and expanded on them by inventing the Curwen hand signs, a way for children to associate pitches to a hand sign.

Teaching children to sing using moveable do solfège (or sol-fa) is found again in the work of the 20th-century Hungarian composer and teacher Zoltán Kodály. Kodály worked throughout Hungary to create ‘Singing Schools’ where children learned music based on singing sol-fa. Today, the Kodály philosophy is a popular and effective way to teach music in a group or classroom. However, there is no reason why such a method cannot be as effectively applied to learning to play the piano. If the piano has the ability to sing, perhaps we should approach it with singing.

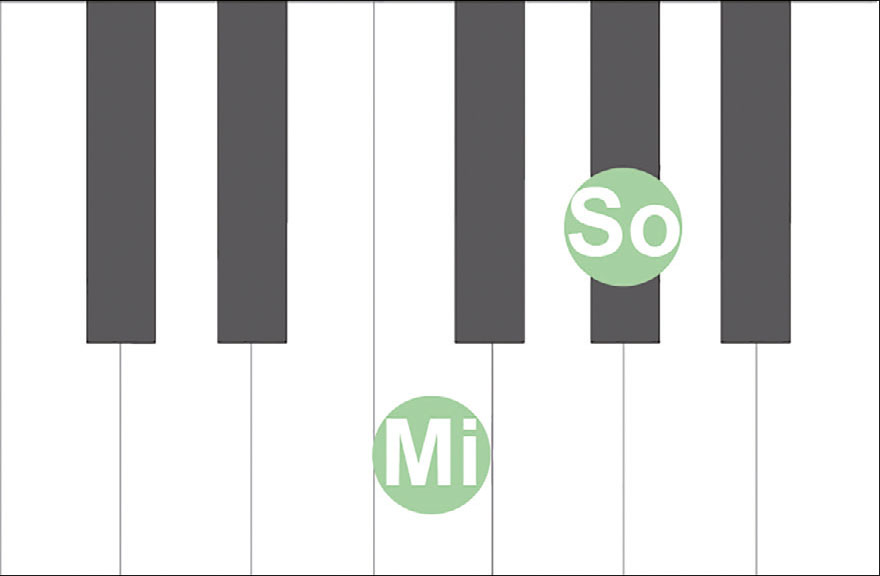

Graphic 2: So-Mi, D flat major

Graphic 2: So-Mi, D flat major

Sing first

Interestingly, it is easy to teach students to play the piano without any type of singing, or indeed any aural training. Students can theoretically learn to play the piano completely visually. The piano keyboard is laid out in easy patterns of black and white keys that can be matched to the black and white notes on the stave. Effectively, students can begin to learn to play the piano with little regard to the fact that sound is produced when the keys are pressed.

However, if we approach the piano with methods found in the principles of Glover, Curwen, and Kodály – specifically if we teach piano by first teaching students to sing moveable do sol-fa – students arrive at the piano with a pre-developed understanding of music. When students learn to recognise the relationships between pitches, they recognise how these relationships lead to phrasing, colour and character. They learn to use the piano to create music instead of music suddenly happening because they have pressed a key.

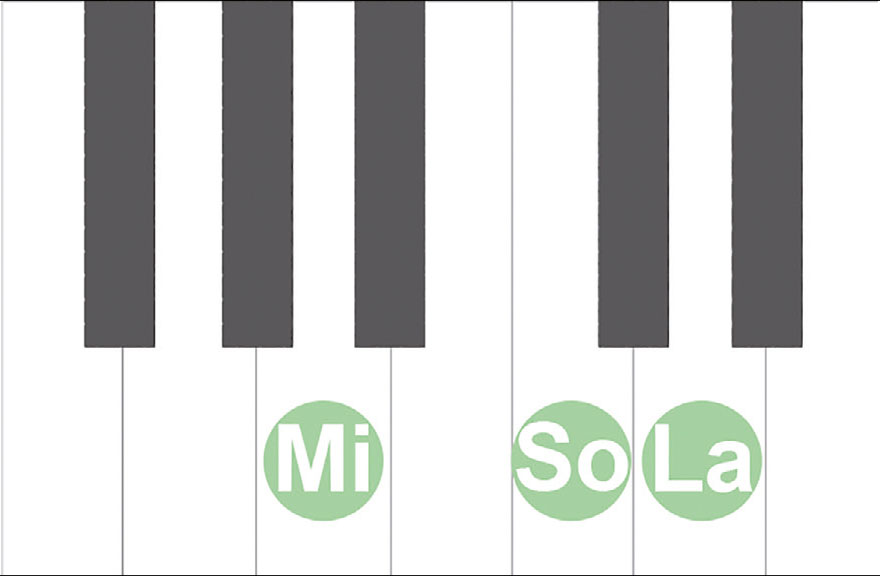

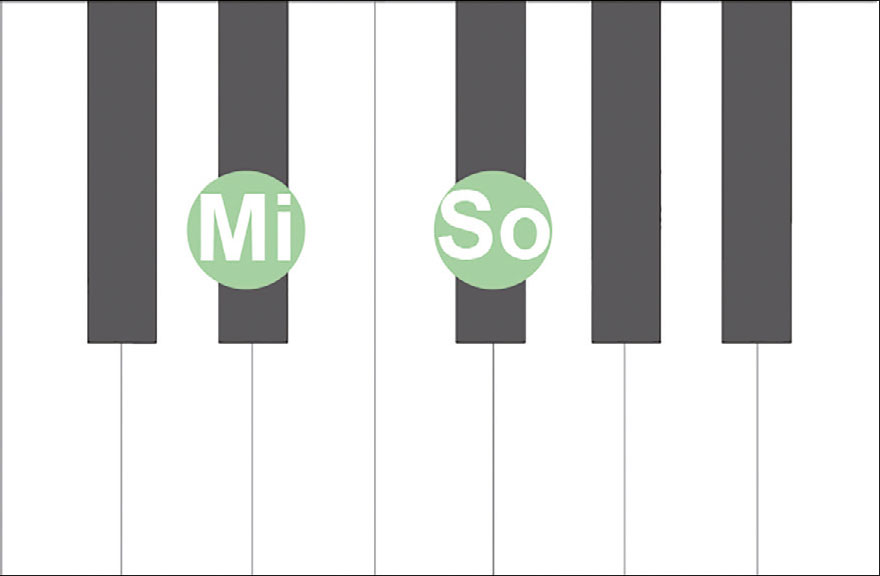

When children sing first and then take their singing to the keyboard, they are able to create and understand music with much greater ease. It is then that the visually spatial patterns of the keyboard can support their understanding of music. If, for example, children learn to sing the sol-fa pitches that are first presented in the Kodály method, ‘So and Mi’, they can easily play these on the piano in many different keys (see graphics 1 and 2). These pitches can be performed on the keyboard in any position, which allows the student to develop a natural understanding of the relationships between the pitches and how they function on the piano. This process can be further expanded by adding the pitch ‘La’, which creates the universally recognisable sequence of tones, ‘So-La-Mi’. Again, these tones can be easily found and played on the piano, confirming what the child already understands of how the pitches sound (see graphics 3 and 4).

Graphic 3: So-La-Mi, F major

Graphic 3: So-La-Mi, F major

Sound before symbol

This begins the journey of learning to decode musical notation. The composer and music educator Carl Orff wisely said, ‘Sound before symbol’. This sage advice suits the piano student who has been introduced to music through singing. The pitches that they have learned to sing can be more or less superimposed on the musical stave. The notation echoes the audiation that they have already established through singing.

The pianoforte is a vast and complex instrument. It has the ability to engage dozens of overtones and can produce many layers of colour and dynamic. Undeniably, it does make a difference whether a piano key is hit by a finger, fist, or an umbrella. If singing tone exists within the player, they can recreate it on the instrument. The singing pianist creates a singing piano.

Graphic 4: So-La-Mi, G flat major

Graphic 4: So-La-Mi, G flat major