I, Asha Bishop, am 18 years into the profession, and yet it feels for me that my exploration of musical understanding has only just begun. I've spent years writing and rewriting my own curriculum, often fuelled by the expectations of senior management and the latest teaching and learning initiatives. If asked, I could articulate what progression looked like in Music, but was always restless with the topic-based learning and the feeling that, although students were kept busy in my lessons, deep musical understanding was unachievable at KS3 with just one hour a week. I felt like it was something best tackled at GCSE and A Level.

There has been plenty of chin rubbing, and attempts to put into words what ‘musical understanding’ is, but it still feels like there's a lack of clarity and agreement. A few observers get it right, like Kevin Rodgers in his 2020 ISM report Musical understanding: an executive summary (tinyurl.com/45p493hw); but there's still a fundamental problem with many approaches to KS3 teaching, and that is that it's entirely possible to develop physical skills and commit musical terminology to memory while at the same time completely side-step teaching real musical understanding.

In working with Liz, I've been re-evaluating my musical understanding in a way I haven't done for many years, or possibly ever. I'm daring to challenge my own thinking, practice and assumptions and, as a result, the students in front of me are learning and understanding more than I've ever seen before. One student, completely unprompted, left a lesson saying: ‘I actually learned how music works today.’ I frequently have kids saying, ‘Ah, I get it now.’

I feel that I now know what I want to communicate, and what I want students to learn through the guidance of this new approach.

Liz Dunbar continues:

We all know that the development of musical understanding doesn't just happen in allocated academic curriculum time. It happens for our students at home, in school practice rooms, VMT tuition, rehearsals and ad hoc jam sessions. It happens in living-room bands, professional studios and concerts – all over the place. But it's in your classroom, through your curriculum, that students' musical understanding can be developed and shaped in a structured and meaningful way. It doesn't need to be by chance; it can be by design. And if students can take an ‘Ah, I get it now’ nugget from your lessons, and explore and enrich the rest of their musical lives with that understanding, even better.

The more experience we have in the classroom, the better we get at refining and adapting our teaching materials to make them fit for purpose; but let's face it, one of the key barriers to making significant changes to our teaching is time. Finding the time to rewrite and design from scratch is hard. With that in mind, all I'm suggesting in what follows are minor tweaks, not a massive rewrite.

Little robots or musical thinkers?

It's Year 7 lesson 1. Rather than leaving a warm-up clapping game here, try the following:

Rhythm

Ask students to clap Ex. 1 (below) back to you. Engage them with what's happening musically here. Get them thinking about what they're actually doing, experiencing, hearing, seeing by asking the questions:

- What difference does it make when I count us in at the start?

- Is my counting evenly spaced?

- What might I do to change the tempo?

- How do you know what to do with the second beat?

- How can you tell there are four beats in the pattern?

- What happens on beat 4?

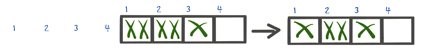

Ex. 1

Then you start asking questions, students are more likely to want to start thinking and engaging with what's going on in sound and ask further questions. I can sneak in the term ‘tempo’ in Year 7 lesson 1, without having taught it previously and without a definition, to find out who already knows what it is, and who can work out what it is because of the context. You've seen and heard it hundreds of times – the high speed ‘3,2,1, go!’ rocket-type count-in from your students. Lead a game or a song that way in your lesson and face a barrage of complaints. Perfect! Let this happen and model the transition from bad to good practice. Turn verbal counting into the silent gestures of conducting; swap roles with a student; watch a pro conductor and discuss why their gestures can be followed and interpreted by well-rehearsed professionals with loads of experience.

Find out how much musical understanding has just soaked in by taking a back seat; split the group, with half sight-reading the first rhythm and the other half responding with the (familiar) rhythm in Ex. 2.

Create a classroom culture in which getting it wrong is part of the learning process, not something to be ashamed or embarrassed about.

Pitch

Now we can move to pitch without the need for any mnemonic about buses, boys, cows or goats.

Ex. 3  Illustrate the four phrases from Ex. 3 in sound and ask:

Illustrate the four phrases from Ex. 3 in sound and ask:

Which of these four patterns am I playing?

- Which pattern doesn't start on an F?

- Which pattern only uses two different pitches?

- Which pattern falls by step?

- How many lines use an F more than once?

Provide visual support, so that every student can answer in sound rather than words, and at a keyboard as in Ex. 4.

Ex. 4  When a student offers to provide an answer that they have worked out by ear, their musical understanding is a million miles away from naming the letters on a piece of paper or from poking the correctly labelled black and white plastic strips on a keyboard. They are hearing, thinking and responding as a musician.

When a student offers to provide an answer that they have worked out by ear, their musical understanding is a million miles away from naming the letters on a piece of paper or from poking the correctly labelled black and white plastic strips on a keyboard. They are hearing, thinking and responding as a musician.

And there's even more musical understanding going on when a student answers in sound and, halfway through doing so, realises that they're on the wrong track. They have heard the error, not seen it or been told they've got it wrong. The stumbling, hesitant rethinking that's happening mid-flight is a significant learning moment, and in that moment students cross a threshold of musical understanding and there's no going back.

Chords

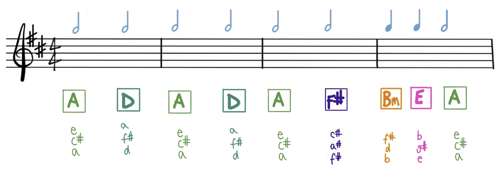

Fast forward to the middle of Year 8. Rather than providing a chord sequence and a bass line such as Ex. 5, equip students with the ability to work out I, V, VI and IV in the key of G, to check their existing understanding of primary and secondary root-position chords.

Ex. 5  Extend their musical understanding by asking:

Extend their musical understanding by asking:

If the chords are G, D, Em and C, where has the F sharp come from in the second bar of the bass line?

- What difference does using an F sharp between them make?

- Why not an F natural? Can we try all three options in sound and find out why?

As skilled musicians, we don't think twice about these things; but for many of our students this will be the first time they have made a connection between the horizontal and vertical, and they are making that connection not only in sound but in context. Providing context is so important – just like those pictures of archeological digs in which a 50p is placed next to the artefact, for a sense of scale.

Granularity

In the early days of developing students' understanding of the composing process, it's nice to explore the granularity of task-setting that sits between ‘play this melody’ and ‘compose a melody’.

After lots of foundation listening exercises with ‘find the three notes that make up this triad’ or ‘what might we use as a bass note’, you've got to move students off the painting-by-numbers stuff and into the craft of melodic improvisation and melodic and countermelodic writing. This isn't a binary process.

I'm back on the discernment thing again. I have found that most students find melody writing really difficult, so all of this has to be done in baby steps, with loads of scaffolding, safety nets and modelled examples from you in response to what's happening live in the classroom. Exx. 6–8 illustrate the process.

The depth of musical understanding that a student gains by improvising, reworking, refining and shaping a lyrical, balanced melody over a diatonic harmonic framework is vast. Our analysis may look like Ex. 9.

In such cases, don't ask ‘do you like it?’ or ‘how does it make you feel?’, because students will invent answers to try to either shock or please you – it's not a useful feedback mechanism. Instead, ask:

- What's the significance of the location of the tonic?

- What difference does its absence from the first down-beat of phrase 3 make?

- Can chord III be replaced with chord I? Can chord VI be replaced with chord IV? Go and try it out. Does it work harmonically?

- What does the inclusion of chords III and VI bring to the party?

- How does the second phrase differ from the first?

- Would the melody still work if the second phrase was identical to the first? Go and try it out.

- In bar 16, we're left hanging. Is this the end? What do you think might/should happen next?

Now listen to it in context and find out what this composer chooses to do: tinyurl.com/yhj23p9j(pick it up at 00:40).

None of this is unfamiliar territory to us, but most of the thinking behind it is a complete mystery to our students, so investigate it with them. Talk about the ‘whys’ and ask a few ‘what ifs’. Do fewer units of work at KS3 and go deeper. It's the simplest thing to modify in your teaching, either with new or existing schemes, and over the three years of KS3. The ways in which you explore and unpick music in your lessons and rehearsals can have an enormous impact on students' musical understanding and appreciation of how music works.

Further examples of this way of working can be found at tinyurl.com/3hczdhm2

(Artwork, score fragments and annotations by Liz Dunbar)