As part of the assessment at each grade in the new LCME Musical Theatre for Singers syllabus, candidates are asked to demonstrate a series of vocal exercises of their choice, to showcase technical skills and to prepare and focus at the beginning of their assessment. The exercises present an opportunity for students to demonstrate process and development, and tailor exercises to specific repertoire and voice qualities. Helpfully, the exercises can connect to the programme of songs that follows, and can embrace articulation, tone, dexterity, expression, breath control/management, vocal stretches, and a variety of voice qualities and onsets. LCME’s approach to the exercises is also flexible with regards to key choices, range and tempi, and whether or not the exercises are performed from memory.

Specimen exercises

In support of this new technical component of the assessment, LCME has published on its website specimen exercises and tips for developing vocal and musical skills. The specimen exercises are designed to ensure that there is an incremental increase in pitch range as you progress through the grades, in line with expected age range, and an increase in dexterity when it comes to articulating texts. In addition, the published exercises gradually broaden the range of vocal qualities to those expected when working in musical theatre. The exercises also take into account important physiological possibilities, and issues not always apparent from the printed page.

To give a flavour of the thinking behind the published material, we considered the following areas:

1. articulation

In musical theatre repertoire, text is often set monosyllabically, with little repetition of the text. For instance, patter or rap is included in shows such as Into the Woods (‘Greens, Greens’), Hamilton (‘My Shot’) and in Company (‘Another 100 People’) and, even earlier, in Gilbert and Sullivan operettas or in Meredith Willson’s The Music Man (‘Rock Island’).

Tongue-twisters can focus candidates’ minds on clear delivery, which is essential in this genre, and speed. Here are some examples, which can be spoken or sung using one note:

- Supposed to be pink pistachio, supposed to be pistachio pink

- The thirty-three thieves thought that they thrilled the throne throughout Thursday

- Six sleek swans swam swiftly southwards

- Kitty caught the kitten in the kitchen

In the exam, each tongue-twister is performed twice, with a breath in between, and should be as fast as possible while maintaining clear diction.

2. range

To cover a wide range of styles and genres, singers normally need a wide pitch-range, developed gradually. We suggest roughly an octave at Grades 1 and 2, a tenth at Grades 3 and 4, a twelfth at 5 and 6, and two octaves at 7 and 8.

These days we often hear voices, especially female ones, with a reduced range – using ‘modal’/speech register much of the time by transposing material down by intervals of a third, fourth or, sometimes, a fifth. This produces a tone that is not always consistent with the character. Cosette’s song ‘Castle on a Cloud’, from Les Misérables, for instance, works most effectively sung in the original key; otherwise, she sounds older and less innocent and vulnerable.

Focusing on this speech register also limits the development of the upper register, thereby compromising vocal longevity, stylistic breadth, repertoire range and vocal health. Appropriate examples such as those found in the LCME specimen exercises can complement rather than detract from the flexibility and strength found in the lower register.

3. key

It is important to note that composers often make specific and informed decisions when it comes to keys. Take, for example, Stephen Sondheim’s own remarks relating to Mrs Lovett’s ‘The Worst Pies in London’ (from Horowitz: Sondheim on Music) from Sweeney Todd, or, from the same musical, Johanna’s song ‘Green Finch and Linnet Bird’, which loses character, intensity and edge if transposed down too far.

In the recent 2023 remake of the musical film A Little Mermaid, meanwhile, Ariel’s evergreen song ‘Part of Your World’ has been transposed up (into G flat), and additional higher notes have been added. This is a good example of a higher key-choice/tessitura complementing the heightened emotion and yearning in the lyric, and the youth of the character singing it. The key also allows for extending the range, and exploring a variety of voice qualities and colour.

It is also true, of course, that composers will sometimes write with a particular voice in mind, and will choose a key solely to complement that performer. Serious consideration should always be given, however, to the musical and dramatic aspects in relation to the key choice for any song.

As examiners and teachers, we encourage performers and teachers to be careful not to transpose too far downwards, as this can be at the expense of technical development and the ability to portray character and emotion convincingly.

4. enunciation, dynamic and onset

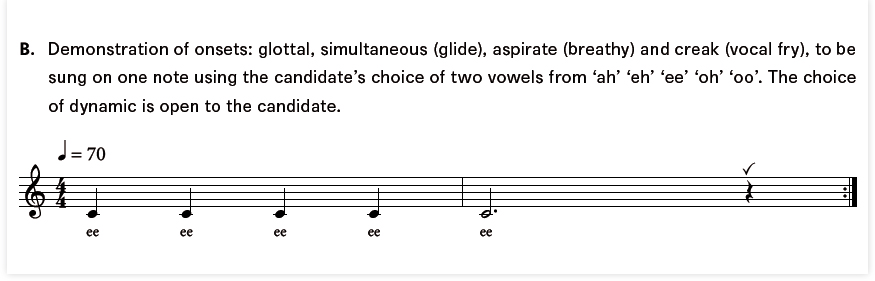

The LCME specimen exercises encourage clear-sounding vowels for more effective enunciation, as in example B below. These are also an opportunity to experiment with accents, and to work on dynamic control, partly so that this activity is conscious and partly to increase the dynamic range as the voice develops.

Specimen exercise from LCME

Specimen exercise from LCME

Exercises covering the range of an octave or more highlight the need to change registers. This encourages learning to integrate and match registers, whether on vowels or lip-trills, for example.

We often hear non-legato slurs in musical theatre and rock and pop performances. These can be detrimental to the text, in terms of clarity, and vocal health, so the slurring in some specimen exercises draws attention to this. The exercises with staccato help with training accurate pitching at the start of a note.

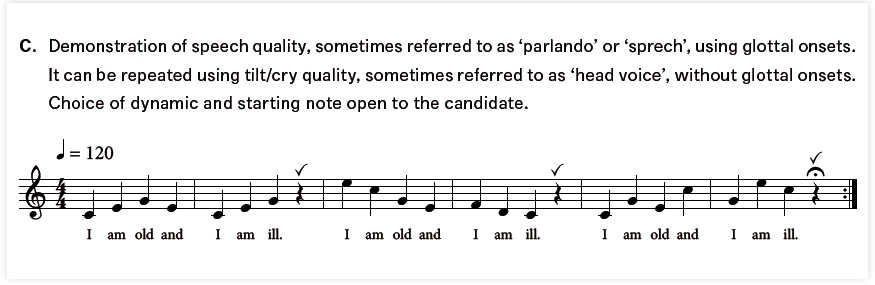

The specimen exercises at the later grades also include onsets. The term ‘onset’, or ‘tone onset’, is increasingly used in singing and describes how the vocal folds and breath come together at the start of a note. (The term ‘offset’ is used to describe how notes end.) Musical theatre singers are required to use a wide range of vocal colour, and the onsets assist in expanding this range. They’re also crucial for clear and accurate diction.

Using a variety of onsets complements developing a variety of vocal styles. It also helps convey character and emotion. We strongly encourage teachers and students to incorporate onset exercises into their regular warm-up regimen. Four common types of onsets are:

- GLOTTAL: Clean attack, direct tone, good for up-tempo songs with rhythmic energy.

- BREATHY, ASPIRATE: Air flows through the vocal folds before these close. Sometimes an unhelpful (unconscious) habit, this can be useful to convey emotions such as fear, nervousness or intimacy.

- GLIDE, SIMULTANEOUS: This onset is most associated with ‘classical’ or canonical repertoire. It is neither an abrupt attack, as in the glottal, nor breathy, as in the aspirate.

- CREAK, VOCAL FRY etc.: Detrimental to vocal health, this suggests a laissez-faire attitude, indifference or even laziness when applied in conversational speech. However, it can be a useful onset when part of a warm-up routine, and can convey a certain attitude of a character.

All these onsets are heard in everyday speech, so are easily accessible to singers. However, in speech they are applied unconsciously, usually correctly, and when applied consciously they can aid clarity, speed and vocal health. Onsets are also often linked to specific vocal qualities; for instance, the glottal to ‘speech quality’ or the lower/speech/modal register; the aspirate to a falsetto/breathy quality, and possibly to the falsetto register; the glide to the ‘laryngeal tilt’, which results in ‘singing quality’ in the upper register (usually); and the ‘creak’ to much of the lower-middle range, particularly when part of a warm-up.

Example C, from the specimen exercises, demonstrates glottal onsets:

Closing thoughts

Although such exercises exist in the musical theatre pathway, they are suitable and often appropriate for a myriad of vocal styles and genres. We hope that students and teachers alike will enjoy incorporating these technical exercises into their musical diet, and will use them to enhance their enjoyment of the exam journey.

For further reading, we recommend the following:

- Chapman, J.L. and Morris, R. (2021) Singing and Teaching Singing: a holistic approach to classical voice. 4th edn. Plural.

- Williams, J. (2012) Teaching Singing to Children and Young Adults. 3rd edn. Compton.

- Kayes, G. (2004) Singing and the Actor. 2nd edn. A&C Black.

- Goldsack, C. (2022) The (Not So) Simple Science of Singing. Lulu.

- Sutton, A.M. (2023) The Heart of the Breath. Compton.

- Harvard, P. (2013) Acting Through Song: techniques and exercises for musical-theatre actors. Nick Hern.