There are few areas of music that have developed as rapidly and profoundly as video game composition. In three decades, the 8-bit monophonic motifs of Super Mario Bros. have given way to intricate, highly complex orchestral scores. Composing for video games now comprises an enormous chunk of our creative industries. The discipline is also fully integrated into the art world: film composers now want to score for games and vice versa. (In fact, the line between film and game is semi-permeable – the Star Wars franchise now places equal emphasis on both aspects of its offering.)

In 2008, the student-aimed classical music magazine Muso published an article entitled ‘Console yourself’ (disclaimer: I was editor at the time). In it, the composer Tommy Tallarico – whose career spans the history of console games, from Prince of Persia and Cool Spot to Tony Hawk's Pro Skater and The SpongeBob SquarePants Movie tie-in game – makes the bold assertion that ‘if Beethoven was alive today, he would be a video game composer’. This isn't as flippant as it might appear. Composing for video games is an enormously challenging process that requires creativity and artistry. ‘A fundamental aspect is that the music is cyclical and often layered in a way that enables tension to be built or deconstructed,’ explains Stephen Baysted, a composer and professor based at the University of Chichester. ‘The reason for this is that because games are interactive, the player's decision-making processes, and how they progress through the game, must be accounted for in the music. The illusion is that the game player imagines the music is accompanying their particular journey. The only way the music can do that is by using a system of loops – for example, if a player stops, a loop can continue until the player has made the next decision. The problem is unpredictability: the player may go down the corridor to meet the baddie and then change their mind and turn around. That's what lies behind this fundamental structural difference.’

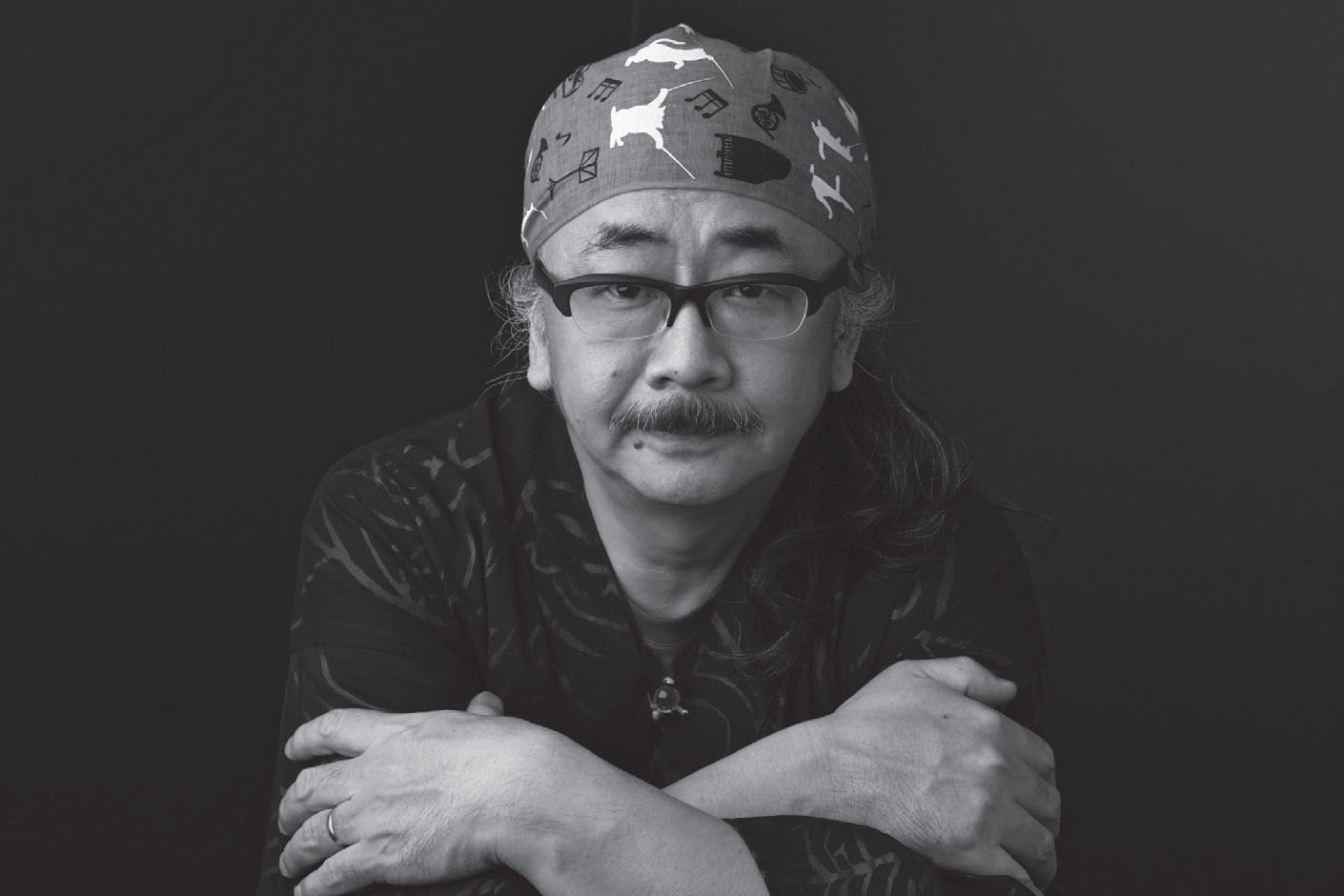

Nobuo Uematsu, composer for many of the Final Fantasy series, is on the A Level syllabus

For this reason, the music can be seen as an off-shoot of Minimalism. Baysted describes using layers in a ‘Reichian way’, creating music in particular blocks, often containing different instrumentation. The skill comes from working out how the loops will accompany action as it unfolds and create a musical narrative. This often requires the composer to work with the game developers throughout the process, rather than in film where the composer generally writes a score based on a finished product. ‘With some of the new open-world games the number of hours of gameplay can be huge. That in turn necessitates a lot of music,’ explains Baysted. ‘Composers do work together quite often – it's a team sport.’

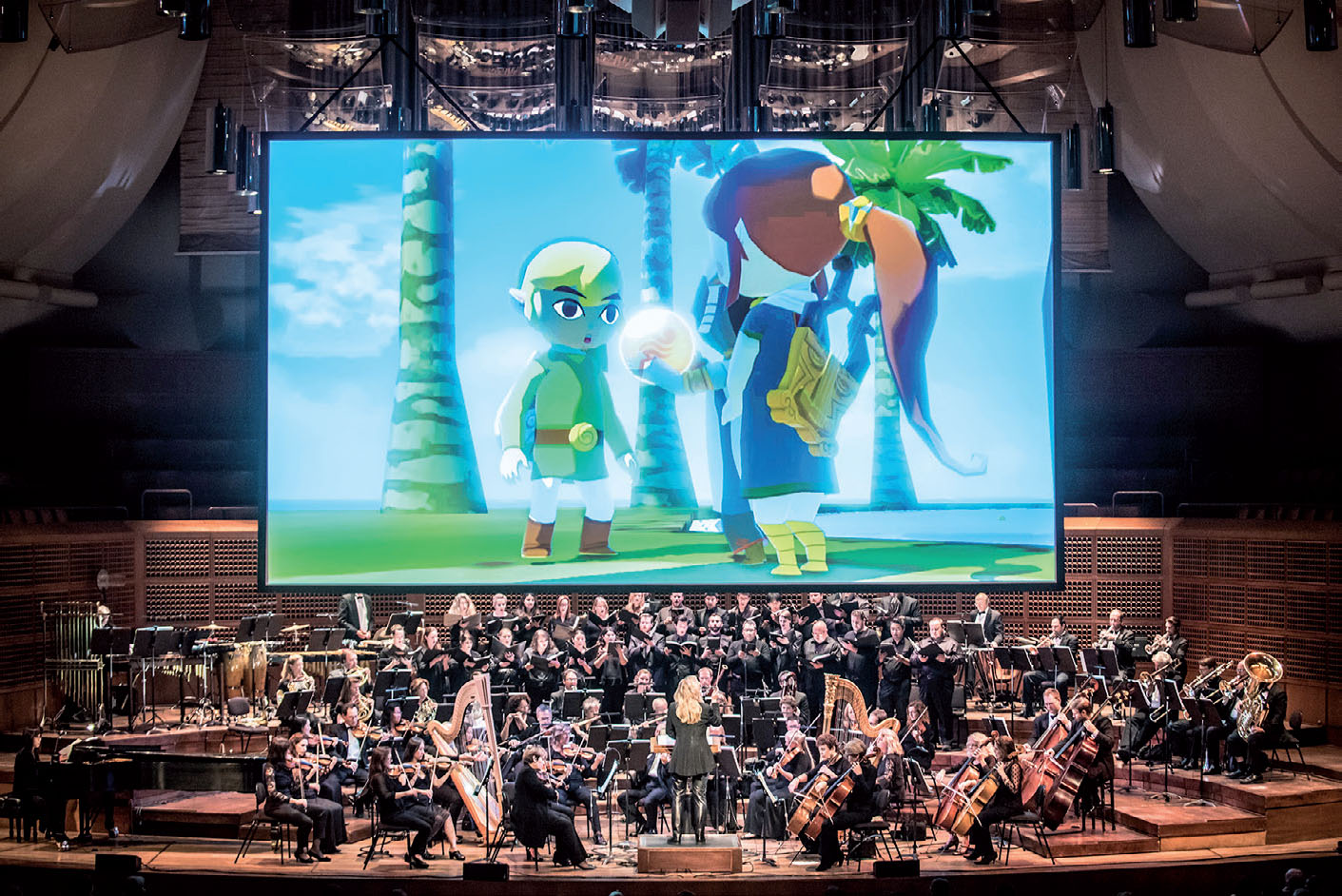

The first consoles offered a small number of monophonic voices, meaning that composers were limited to a texture no thicker than a triad. The Sega Mega Drive later provided six voices, and then CD-ROM enabled multiple recorded instruments. Streaming opened up greater possibilities – contemporary scores can be enjoyed as an art form in their own right. In the last few years, the music has moved from console to concert hall, as events like Video Games Live bring video game music to the stage, with orchestras and choirs performing arrangements of the score while video footage and interactive segments create a quirky immersive experience. These events feed into the popularity of cosplay (short for ‘costume play’) and live action role play, both seeing fans dressing up as their favourite characters. Our fascination with nostalgia is important, too, with several of the retro soundtracks – such as Space Invaders and Pac-Man – featuring alongside scores to newer titles such as Halo, Final Fantasy, Medal of Honor and Horizon Zero Dawn.

The scores are gaining such popularity in their own right that a new ensemble dedicated to the repertoire has emerged. The London Video Game Orchestra was founded by Galen Woltkamp-Moon, who was inspired by events including the Final Fantasy ‘Distant Worlds’ concert at the Royal Albert Hall and The Legend of Zelda 25th anniversary concert (the latter was hosted by Zelda Williams, who was named after the titular character by her father, the comedian Robin Williams). ‘I brought these ideas to an orchestra I used to be in and we wound up doing a geek-themed concert which included video games music – it was the best-selling concert they've had,’ says Woltkamp-Moon. ‘I have always had a passion for video game scores. I found sheet music and MIDI files online and often played them on flute, clarinet and piano.’ The music is also a regular fixture on the radio and via streaming platforms. In 2017, Classic FM's series High Score, then presented by composer Jessica Curry, became the most popular programme on ‘Listen Again’ in Classic FM's 25-year history. í-mear Noone, composer for World of Warcraft and its expansions among others, will present the programme from June. Baysted believes that bringing the music to wider audiences is wholly positive: ‘For a composer it helps to legitimise what they're doing, which in turn is a motivational factor to strive to create the best music you can. Knowing it could be played live and on the radio makes a composer feel as though they are doing something culturally significant.’

‘Console yourself’ informed readers that, at the time of publication, there was ‘no specific training’ for composers interested in exploring the byways of video game music. Today, there are dozens of courses, such as the Music and Sound for Film and Games MSc at the University of Hertfordshire or Sound and Music for Interactive Games MSc at Leeds Beckett University. Video game music is credited with introducing an entirely new audience to classical music, through games such as The Dig, which features excerpts from Wagner. Baysted points out its use in teaching composition: ‘the 16-bar loops are a great entry point, demonstrating colour, texture and rhythm without getting bound up by rules of harmony.’ Woltkamp-Moon recommends the music of Octopath Traveler for the newcomer, along with The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. At the other end of the spectrum, video game music has become an academic pursuit, with the world's first music and game sound journal about to be published by University of California Press (Baysted is on the editorial board). There are lively artistic debates surrounding the role of the gamer in the music, and to what extent they can be considered co-composer. Ultimately, this is a genre that looks set to grow in reach and complexity. ‘There is a huge amount of scoring and work,’ concludes Woltkamp-Moon. ‘I definitely see this genre becoming bigger and more popular than film soundtracks.’ The game is not over.

Woltkamp-Moon was inspired by The Legend of Zelda 25th anniversary concert series

London Video Game Orchestra plays at Theatre Peckham on 15 June. A new six-week run of High Score begins on Classic FM from 22 June.