‘It's hard to ignore a child with a trumpet,’ says Jim Trott, founder of Brass for Africa. Who'd argue with that? It's a handy way to sum up the charity's mission: to work with children and young people who have been ignored.

Trott, an airline pilot and keen cornet player, set up Brass for Africa (BfA) just over a decade ago with a set of instruments donated by his son's junior brass band. Today the charity works in Uganda, Liberia and Rwanda, employs 40 African staff and works with a thousand children and young people each week in a variety of settings. There are currently 30 BfA brass bands.

A large proportion of the children and young people BfA works with are living on the streets, in orphanages or in juvenile rehabilitation centres. Many are living with disability or HIV/Aids. BfA also works with teenage mothers.

Lizzie Burrowes, BfA's director of music education, and Tamale Derrick, music and life skills teacher and musical resources assistant, are both based in Kampala, Uganda. They took time out of their teaching rounds to tell me about their work and the goals of BfA.

‘I'm responsible for the quality of the musical delivery and oversee the musical operation and direction of the organisation,’ says Burrowes. ‘All of our teachers began their journey with Brass for Africa as disadvantaged children benefiting from one of our music programmes, and over several years we have trained them as musicians and as teachers. I manage and mentor the Brass for Africa teachers and I'm responsible for their musical training and development.’

I ask what her typical working week looks like, imagining it to be very different from that of a class teacher or peri here in the UK. She tells me that, among other things, she teaches the Ugandan teachers – currently 17 in total plus five apprentices – who are all aged 18-29. ‘Delivering and monitoring a high-quality education to so many people living in challenging circumstances is a complicated operation,’ she says.

Burrowes dedicates a day each week to training the apprentice teachers. ‘We're developing their teaching philosophy and ability to teach and manage different levels of bands, including interacting with children and young adults in a variety of challenging circumstances. We also teach overall musicianship including aural training, playing, music theory and conducting, as well as professional development.’ Other practical and theoretical music classes for teachers are spread out across the week, depending on their own teaching timetables.

Burrowes is partly based on the BfA compound – surely the only office in Uganda with its own bandstand. The rest of the time she's monitoring teachers and assessing the progress of learners in the various different settings where BfA works in partnership with local organisations.

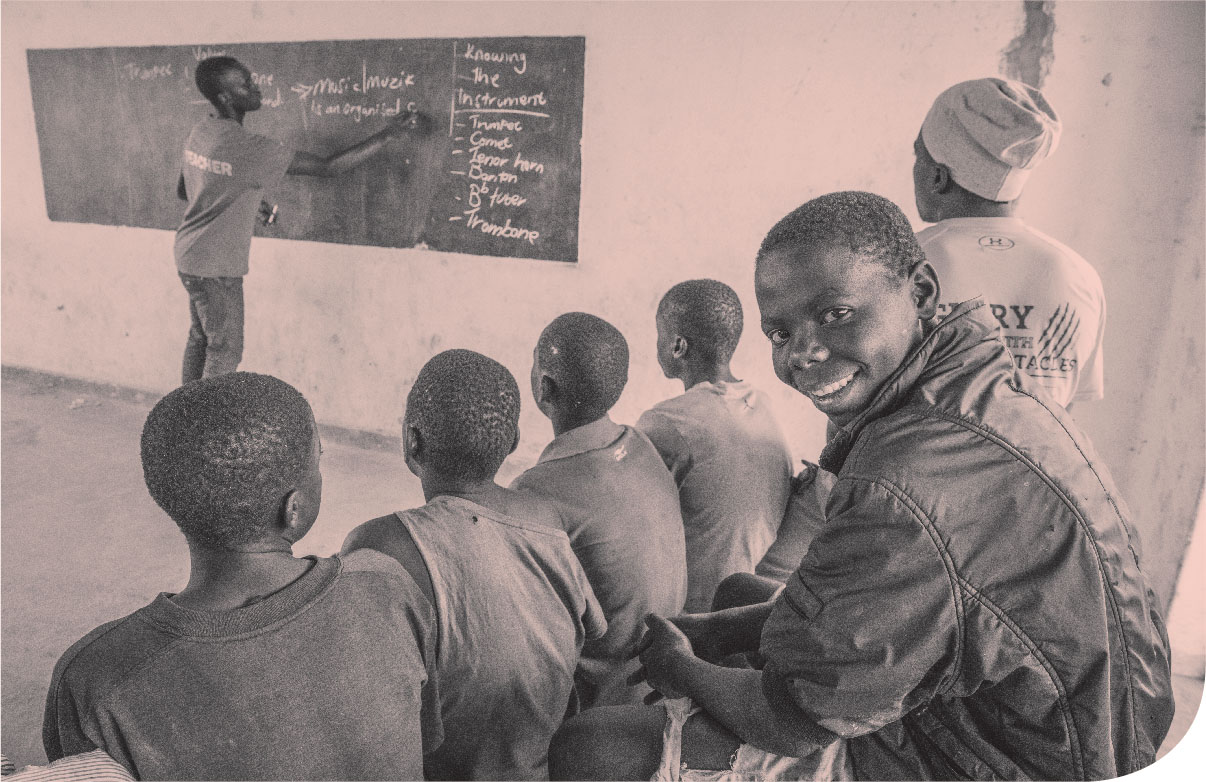

‘The environments can range from classrooms or the grounds of orphanages and children's homes to schools and rehabilitation centres, often based in informal settlements – known locally as slums’, she tells me. ‘We work in rural and urban areas, and lessons take place both inside and outside.’ BfA works with children aged from four years old, and many continue to adulthood. Large numbers of brass pupils also begin as young adults.

‘No matter where we are, I can guarantee that if you walked down the road towards the venue, you would not believe your ears when you heard the sound of a BfA brass band,’ says Burrowes. ‘If you turned the corner and saw a class of young people from that community engaged in a music lesson, concentrating on reading music, persevering even when something was hard to play, working in a team, and presenting themselves confidently, you would be amazed.’

Grassroots involvement

Back at the BfA compound, Burrowes conducts the brass band made up of all the teachers. Tamale Derrick is in the trumpet section.

‘Music has a lot of things involved,’ he says. ‘There is teamwork, and you learn a lot, because, for me personally, music makes me concentrate. Through music I meet a lot of people – while playing in a band, we are so many – you can't just be thinking of yourself.’

Derrick teaches five days a week, including at Nsambya Community Band and the Good Shepherd children's home. ‘I feel so happy whenever I go to Good Shepherd’ he said. ‘When I see I've made that child play from just C, and now I see them improving, playing low C and high C, being able to read music – this is so wonderful for me.’

He places a lot of importance on the ‘life skills’ part of his role. ‘The children [at the Good Shepherd home] were so shy, they could not stand on the stage and they had a lot of fear. But [they came] through that and I see that they have a bright future – because through music they develop a lot of skills which are crucial in the real world.’

Derrick also works in BfA's instrument repair and maintenance workshop and only began learning trumpet with BfA four years ago. Burrowes, meanwhile, comes from a musical family and was a chorister at Salisbury Cathedral as a child and later a choral scholar at Oxford. I asked her what led her to Kampala and BfA.

‘I started teaching music in my early 20s, and when I was teaching at Reading Blue Coat School, I met Jim Trott and his family,’ she tells me. ‘While I was still teaching at the school, I began volunteering for Brass for Africa in my holidays, first visiting Uganda in 2014’. She went on to be director of music at St Dunstan's College, south London, and continued the relationship with BfA. ‘When a full-time position for a director of music education came up, I felt as though in my heart I was already there, and I went for the job’.

The instruments are relatively easy to maintain and repair, withstanding years of love, regular travel, and daily dust and humidity

Like many of the children and young people he teaches, Derrick grew up in an orphanage. ‘Growing up in an orphanage is not something that you would desire, and the conditions of being in a slum area mean there are so many habits which you can learn like stealing, or giving up because you think things are not happening the way you want.

‘You want good things but you can't afford them, but to be able to not give up and just keep on going and going – this is something that I am proud of. And I'm also just happy that I can share it with children. It gives me much happiness in my heart to see the Good Shepherd team go on stage and perform without hesitating, being proud of who they are. When I see this I know I have done something that I am proud of.’

Derrick now sees himself as a role model. ‘Many people in my society look up to me,’ he says. ‘Whenever they are giving good examples of people to their young children, they include me. Because I've been a teacher in my community – that's not something so easy. Most people, when they looked at us [learners on the BfA programme], they thought that we had no next step, or they thought that we can't achieve this. Just being able to achieve this [being a player and teacher] is so huge in my society.’

Of course, not every BfA pupil goes on to be a BfA teacher themselves. Other graduates of the programme have gone on to pursue higher education, receiving support from BfA that they would not have had access to were it not for the voice and visibility they gained through playing their instrument, according to Burrowes. Some have gone on to be professional performing musicians or music teachers at other institutions in Uganda.

Why music – and why brass?

I ask Burrowes and Derrick why and how music can help people to achieve their goals. Why music and not, say, sport? And why brass? As BfA's founder says, no one can ignore a brass band – but what happens once our attention is caught?

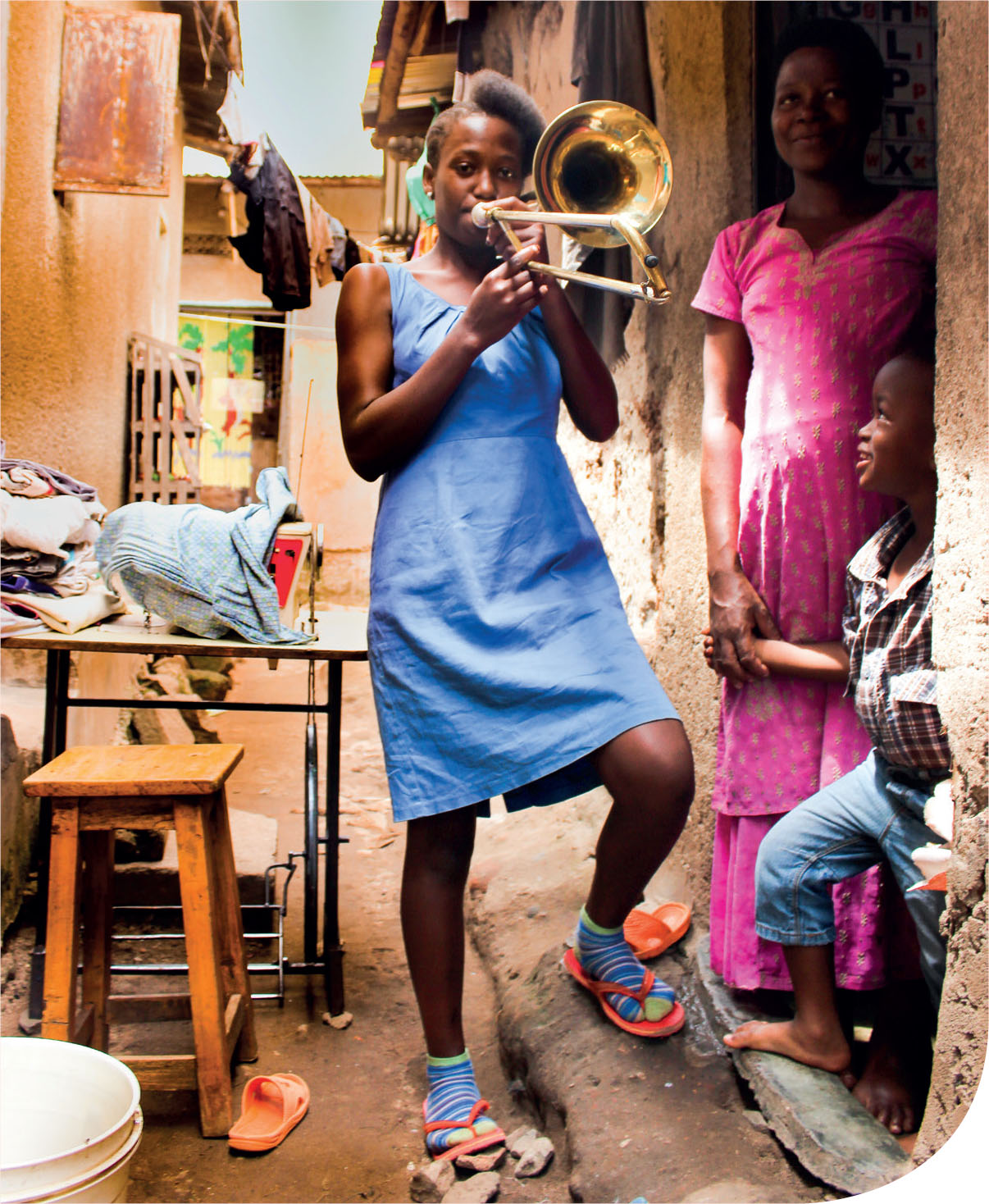

‘When a child has been sidelined, left with low self-esteem, an inability to look anyone in the eye and a feeling of worthlessness and hopelessness, it is incredibly empowering for them to pick up an instrument and make a loud noise’, Burrowes tells me. ‘Learning to play an instrument brings about huge personal development’.

BfA has identified eight key attributes: self-confidence, resilience, grit and perseverance, problem solving, leadership skills, concentration, teamwork and communication skills. ‘Any young person preparing for their future would want to develop these life skills, yet most students that enrol on our programmes do not have any other opportunities to do so,’ says Burrowes. ‘We aim to assist young people to achieve their potential, and these skills are the key to their success.’

Burrowes sees music as an obvious way to encourage students to work on these attributes. ‘Music is cool! It is the hook for us, drawing in students who are excited and interested in the sound and also the presentation and identity of the musicians they admire.’

They're not just loud noise machines – brass instruments have many practical qualities to recommend them. And as lots of BfA's work takes place outdoors, this is no minor consideration.

‘The sound on brass instruments is essentially made in the same way for each, making ensemble learning from scratch a surmountable task,’ says Burrowes. ‘The instruments are relatively easy to maintain and repair, withstanding years of love, regular travel, and daily dust and humidity.’

The physical conditions in Uganda and the UK are certainly different (although instrumental teachers anywhere will recognise the need for resilient instruments). I ask Burrowes if she found working in music education in the two countries to be as great a contrast. She tells me there are underlying similarities to her work in both countries. ‘It's simultaneously exciting, challenging and rewarding, and there are many opportunities for personal and professional growth.’

Many UK music educators will recognise BfA's ‘transferable skills’ approach – the way that music can help children in challenging circumstances to acquire not only skills but confidence. Many of us know – or are – strong role models who open up the possibilities of music for young people. In a tough environment for funding, we also have to work hard to reach as many young people as we can.

‘When you give music education to young people who have faced neglect, abandonment and abuse, who have been marginalised by society, who have no material goods and nothing to feel proud of – music is life itself,’ says Burrowes.

She adds: ‘Our patron [the trumpet soloist] Alison Balsom said that although some people would say you don't need music like you need food and water, that isn't true because life is about more than just surviving – it is about flourishing as a human being.’

Derrick describes how learning to read music had been a revelation for him. He previously played what he describes as ‘memory music’.

‘It was so amazing – to see something I'd been doing for four or five years.’ He laughs as he recalls working through A Tune a Day and Simply Brass.

The younger generation is now coming up behind him. Fifteen-year-old Aisha Nassaazi, spokeswoman for Gloneva Brass Band, says, ‘Children like me born and raised in slums, children born in rural areas and raised on urban streets; children born to dysfunctional families and addicted parents, many of these children have questions that need urgent answers.’ Music may not provide ready-made answers, but it can provide tools to help young people like Aisha keep asking questions.

When I ask what he is most proud of, Derrick says: ‘Brass for Africa is changing disadvantaged children's lives through life skills and music – I've seen children coming from nothing and being somebody through music.’