My previous article (MT January) focused on writing a short piece using just one note. This month's column centres on writing a short piece employing two notes. We are expanding the compositional process, and this time students can use two notes in any part of the keyboard, or on any instrument. A certain familiarity is required with the instrument chosen for this task. Ensure students are aware of instrument ranges and capabilities; this in itself is a useful exercise and helps to build a knowledge bank for orchestral or ensemble writing later on.

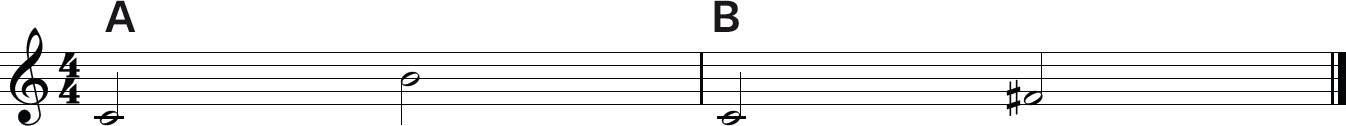

Take manuscript paper and a pencil, or digital equivalent. Prepare the time signature and key signature (if necessary), and select a tempo. Choose two notes; these might be next to each other or separated by an interval. Students may even like to select clashing intervals such as a major seventh (A) or augmented fourth (B) (see Fig 1).

Fig 1

Students may wonder how these two notes sound together, so play them on the piano (if there's one available – or go for a digital option). Ask them to play them as well, so they get a feel for the pitches and sound. Then try to ‘hear’ how those notes might sound on the instrument being composed for. It's not always possible to write down exactly what we hear in our minds, especially when we are just learning to compose, but attempting to do so does provide focus, opening up new possibilities and taking music off the page and into reality.

Now that the pitches have been secured, students must cast their imaginations. What do they hear? Can they hear these two notes in tandem? Or do they hear them being played together or at the same moment (not possible on all instruments, but it can be effective on string instruments or the piano). Are the notes in different registers, and how do the dynamics change? It can be both challenging and effective to use notes in a different register.

Now try to imagine or ‘hear’ how those two notes might be combined. Will the note patterns be long or short, and what pulse will be selected? How are the notes combined together? And how many bars will each phrase consist of? A four-bar phrase might be used and repeated two or three times, for example – and once this repetition occurs, the piece starts to emerge.

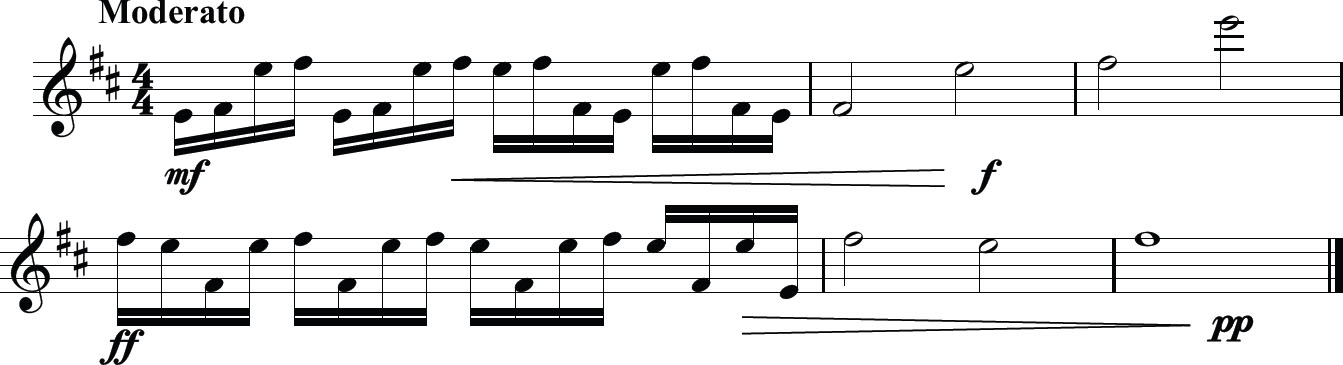

For this exercise, I hear a flute. My piece consists of major seconds in semiquaver clusters, an E and an F sharp, played at a fairly brisk speed. These clusters are followed by a succession of longer notes, before returning to the shorter, spikey note pattern. Perhaps something like Fig 2.

Fig 2

It can be prudent to repeat rhythmic patterns, as this can provide unity and synergy. This is especially important when using more fragmented note patterns, as can be the case when just relying on two pitches. Once a preferred rhythmic or note pattern is found, it could be featured in several phrases, elongating the new piece, therefore providing a vital expansion tool.

Students often respond to stories. Encourage them to use their imagination, possibly steering them towards devising their own drama. Once they have a plot, each sound could be an important part of that story. If the drama contains a beginning, middle and an ending, so much the better. And finally, locating the ‘high-point’ in their story, or the crux of the tale, could signify the climax of the piece; an example of this may be the high E at the end of bar 3 in my example. Now their new piece can really spring to life, as the sounds become meaningful and real.

By employing limited musical means – just two notes, short phrases and a varied rhythmic pattern – students have a vehicle to start interpreting their thoughts in their music.