Look around any Key Stage 3 classroom, in any school, anywhere in England. You will see multiple subconscious percussionists drumming fingers on books or tapping pens on tables. At my school we decided, in the grips of the pandemic, that we would harness these childhood fidgets into a skills-focused spiral curriculum concentrated entirely on percussion playing and artistic citizenship.

For context, the school is a vastly expanding, successful secondary school, having recently developed from an upper school to a fully-fledged 11–19 secondary school. It quickly transpired that students were arriving in Year 7 aged 11 years old with very little prior musical experience or continued musical education.

Each year we feel lucky if we inherit one student who is already having instrumental lessons. The school is inclusive with large numbers of children with English as an additional language and children with additional needs. Initial curriculums were trialled, tweaked, overhauled, and started again. Progress was slow and often frustrating for both student and teacher.

Fine motor skill development became a clear barrier to learning instruments such as the recorder. Weakness and lack of strength in hands made pressing fingers on string instruments a tricky task. Singing, having not been thoroughly developed in primary school, became a sensitive situation when factoring in changing adolescent voices. At the very crux of the issue: the majority of students entering Year 7 could not clap in time to a steady pulse, identify high or low pitches, or tell the difference between a flute and a cello. I looked around Key Stage 3 classes humming with the sound of subconscious percussion. There was a pandemic looming. I already had premonitions about restrictions on resources, intertwined with stringent cleaning regimes. Then, I had a light bulb moment: percussion.

‘One fundamental issue is that the instruments look childish, and here is where artistic citizenship becomes crucial’ © BABIMU/ADOBESTOCK

‘Miss, why do we have to do music?’

Percussion is just as synonymous with classroom education as its woodwind neighbour, the recorder. Like the recorder, percussion in the classroom was a reaction to a reduction of resources during the Second World War. Developed pedagogical concepts such as Orff Schulwerk joined forces with Trinity College's Percussion Band Syllabus and then faded away from English schools. In 2022, show me a primary school that remains without the ubiquitous joy of a ‘percussion trolly.’ The legacy of these projects and initiatives still looms large.

I needed to teach absolute musical basics to enthusiastic but sometimes cynical pre-teenagers. How did I construct a curriculum that quite literally started with learning to feel the beat but did not come across as patronising to the students? Taking inspiration from Kodály and Lucy Green, I swotted up on my knowledge of percussionists with an aim of enculturating the students into the world of percussion. I took an interesting journey to the far-flung percussion corners of YouTube; I spent hours watching documentaries and interviews with percussionists like Dame Evelyn Glennie, Ray LeVier, Chick Corea and Gary Burton, Sami Yusuf, the Bodhrán Boys, West African drumming communities, and military musicians.

I first needed to convince and show my students that percussion was an integrated part of human society – that people from across the world, regardless of gender, sexuality, disability, or ethnicity, all played percussion. Artistic citizenship – showing how music fits into a global society – starts every music lesson. It has had the added benefit of removing the weekly question of, ‘Miss, why do we have to do music?’ Students know how integral music is to life.

Progression and differentiation

And so, to the practical percussion. Originally settled upon as an affordable way of providing nearly 500 students with their own instrument (initially, a pair of drumsticks), it has turned out to be hugely successful. Students arrive in Year 7 to a half-term of body percussion. Yes, we really do start with trying to find the beat – first in standard four time but reaching out to triple and compound time relatively quickly.

Classes follow YouTube play-along videos, appealing to students and almost feeling like a video game. They then move onto composing their own body percussion pieces. At the beginning, loosely following the Kodály principle of prepare, present and practise, students are not introduced to notation. After October half term, drumsticks and notation are introduced. We follow a Kodály-style approach to rhythm, speaking the rhythms first and then playing them with drumsticks on tables. Gradually, we work up to Grade 1 snare drum by the Easter holidays. We assess our students playing a Grade 1 solo piece, and some students by this point have exceeded to Grade 2.

To aid with differentiation, some students perform with the Kodály rhythm syllables written on top of the notation, while others can read fluently. We ask our students to both speak the rhythms and play at the same time. Through this we can see whether students understand the concept of rhythm and pulse, as well as assessing their ability to play it. It is not unusual to hear students able to speak the rhythms fluently while keeping a steady pulse but being unable to keep up with their sticking patterns. This is where speaking the rhythms becomes really important; we can assess clearly whether students understand rhythm, even if they struggle to play it.

Artistic citizenship

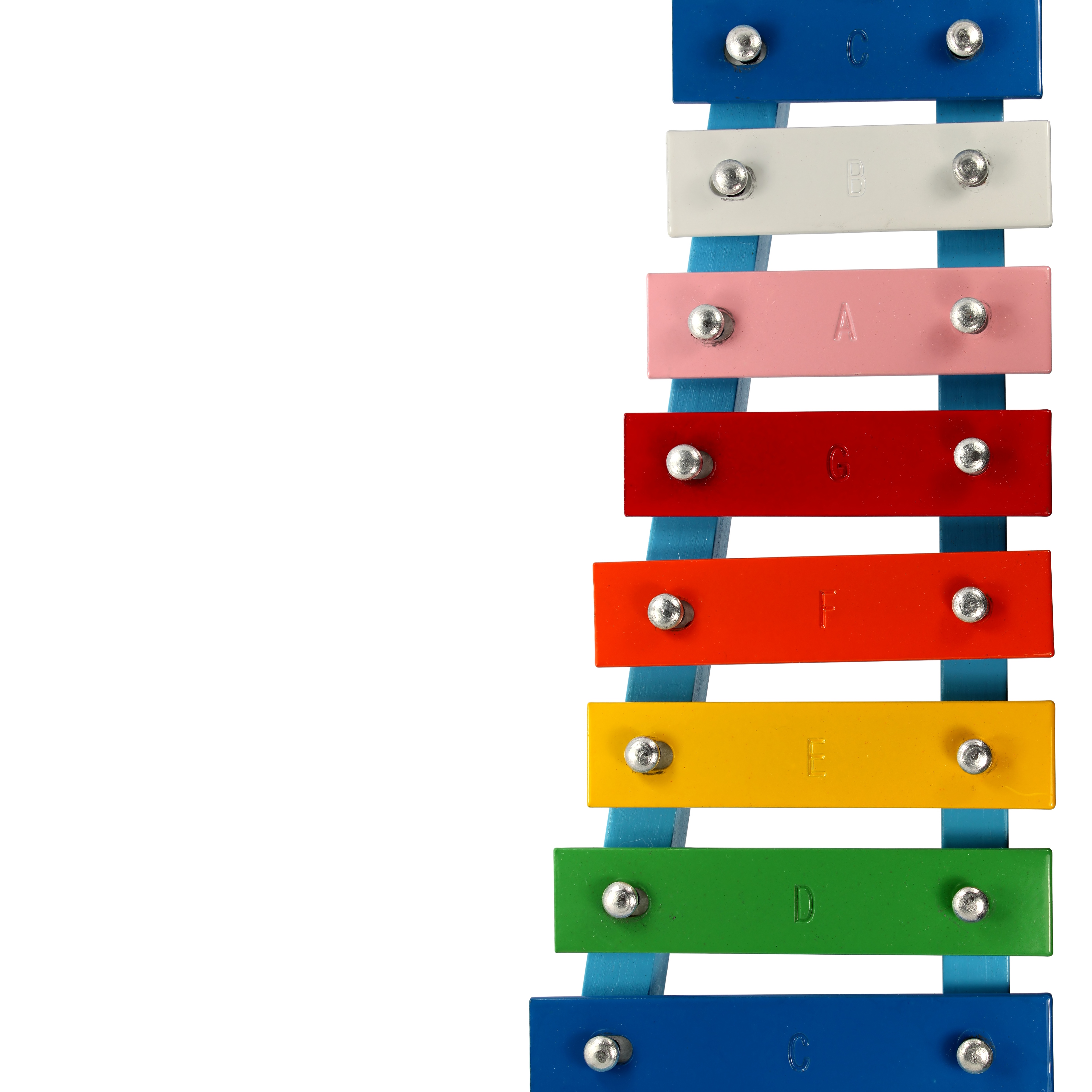

By the end of Year 7, our students are playing and understanding complex rhythms in a multitude of time signatures. This is when we start to introduce tuned percussion. We use basic rainbow colour coded glockenspiels that easily fit on tabletops. We start with just three notes, using colour coded pitch notation. Our students use Curwen hand signs to give a tangible notion to the often-abstract concept of pitch. Everything is first spoken with rhythm syllables, sung with hand signs, and finally played.

One fundamental issue is that the instruments look childish, and here is where artistic citizenship becomes crucial. At the start of each lesson, students have a listening quiz, assessing their knowledge of the musical elements. Examples of repertoire in these listening quizzes always contain a member of the tuned percussion family: the Harry Potter theme tune, the awesome glockenspiel opening of Shostakovich Symphony No. 15, gamelan, composers like Phillip Glass, Steve Reich, Gary Burton – the list is endless and demonstrates real music featuring the instrument students are learning to play. Regularly these pieces have a link to citizenship: creative careers in the film industry for Harry Potter; censorship and Shostakovich; LGBTQA+ rights with Gary Burton. The aim is to show that percussion and percussionists are everywhere in society.

The project has been successful. Our current year 10s are all working towards Trinity Grade 5+ percussion exams; they have had the opportunity to play in an orchestra and work with professional percussionists.

Each one of our GCSE students has a mini glockenspiel and drumsticks to practise with at home. GCSE students compose for percussion; they play together at lunchtimes and, crucially, they love their individual percussion lessons so much they are yet to miss a lesson! For this is all in praise of percussion. It has transformed the music curriculum at my school and is allowing teachers and students to see tangible progress in the understanding of musical elements and the fundamentals of pitch, pulse, and rhythm.