City Snapshots

For group lessons, instrumental teachers need lots of varied resources. It's a hard task, keeping up the pace while accommodating different speeds of learning – and sometimes different instruments. James Rae's City Snapshots is a fun, lively – and useful – collection for flute players, taking in beginner to Grade 2.

The collection is a mini-world tour of 12 cities, including a piece from each destination: ‘Cossack Dance’ for Kiev, ‘Montmartre Waltz’ for Paris, ‘Reggae Nights for Kingston’, and so on. Teachers in schools could use the opportunity to make links to the wider music, language, geography and history curriculum – the pieces are also perfect for school concerts. While there are quite a few world music collections for early-stage players available, most of them require prior musical attaintment, so Rae's new collection is very welcome.

The pieces give teachers and players lots of options and are all in flat keys (maximum two flats), making them compatible with any stray clarinet pupils. Each piece has two homophonic flute parts, one with a slightly smaller range. This gives pupils struggling with higher notes a chance to fully join in while they build up their skills and stamina, and also offers a good introduction to ensemble playing. The piano parts reinforce the style of each song, while allowing for adaptation since chord symbols are provided.

Each piece is very rhythmic, with catchy melodies and clear structures. Rae has made sensible decisions about how to introduce the different styles to young players – ‘Tango Argentino’ leaves the milonga rhythm to the piano, giving young players a chance to hear and feel it without being bamboozled by complicated musicality. The piano accompaniment for ‘Montmartre Waltz’ also has quavers, which will help with the dotted rhythms in the flute melody. Pupils can then look for contrasts with the ‘Oktoberfest Ländler’, also in 3/4 but very different. The lively ‘Liffey Jig’ can be used to work with pupils on 6/8 and encourages them to feel two in a bar, while ‘Lotus Blossom’ has lovely legato pentatonic recurring melodies, which give young pupils an opportunity to work on their tone and support. Taken as a whole, the pieces use a range of different articulations and dynamics, and are an excellent introduction to playing expressively.

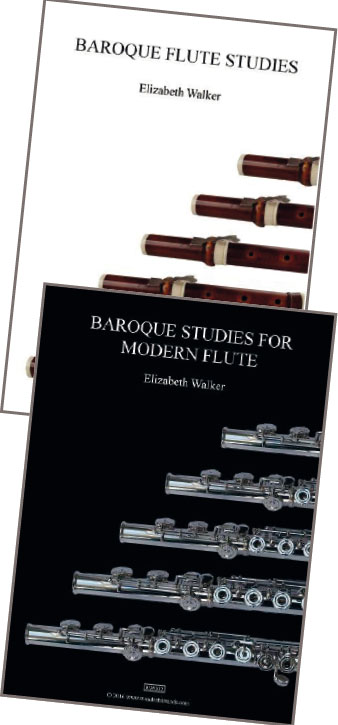

Baroque Flute Studies and Baroque Studies for Modern Flute

When it comes to technique and baroque interpretation, flute players must understand that, pre-Boehm, different keys were much more different. Baroque flute specialist Elizabeth Walker has written two incredibly useful books exploring this, alongside aspects of technique and expression. One is for players of the wooden baroque flute, and its companion volume is for the modern silver flute.

Walker writes: ‘The baroque flute can colour every key differently, due to the natural unevenness between the different chromatic notes. I aim to highlight the contrasts and natural characteristics of each key, and help you discover the palette of colours possible.’

In the baroque-instrument book, Walker takes the pupil through the keys from easiest to hardest. D major is ‘bright’ while keys with the weak note, Ab, have more variety. The section for each key begins with tone exercises, first on the easier notes and then with the introduction of weaker, ‘forked’ notes – those where there is a gap in the fingering. Walker instructs the player to lift the fingers high in order not to affect intonation, and expresses how this contradicts the idea of good modern-flute technique. She then introduces finger technique and articulation exercises – articulation on the baroque flute also differs greatly from that of the modern instrument. Walker has also chosen a wonderful collection of excerpts from solo, duo, trio and orchestral repertoire, so the flautist can apply the techniques practised.

In Walker's modern-flute volume, she translates the lessons on colour and variety to the silver instrument, writing: ‘No doubt many years of study have been spent gaining a full and even tone on the flute. However, variety is now the aim: to find subtle ebbs and flows in the dynamics, length of notes, shape and articulation, whilst maintaining the intrinsic beauty of every note.’

When playing the modern flute, it's very rare not to use vibrato, but on the baroque instrument players use vibrato only as an ornament – often using the fingers rather than the airstream – and aim for a still sound. Many modern players find it very hard – but ultimately useful – to learn to switch the vibrato off, and Walker provides exercises to practise as well as suggesting original sources to read. She also addresses another scary area for some players – ornamentation, by providing clear explanations and suggestions. Any flautists wanting to tackle the Bach Preludes would benefit hugely from using these study books.

Suites no. 1 BWV 1007 and 2 BWV 1008

Once we're past the initial stages, flute players are no strangers to a bit of begging, borrowing and stealing when it comes to extending our repertoire. Renowned performer and teacher Clare Southworth has transcribed some of the world's most instantly recognisable pieces of music for us: Bach's Cello Suites Nos. 1 and 2. In the performance notes she acknowledges that, ‘our repertoire is deprived of the depth and scope that keyboard and string players have always enjoyed. I hope to give flautists the chance to also enjoy some of the most beautiful, complex and challenging music ever written’.

Players will need to be at least Grade 4 standard to tackle some of the menuets and sarabandes, and only Grade 8 players will be able to take on the works in their entirety. The cello part is transcribed two octaves higher and uses a two-and-a-half octave range; on the flute this runs from lowest C to highest G.

These transcriptions are a great way to encourage melody orientated players to think harmonically. We have to ‘be our own bass’ and find the skeleton of the music underneath the fast-moving notes.

Each suite opens with a prelude, both challenging the player's stamina and interpretation, and then moves through a string of dance movements – allemande, courante, sarabande, a pair of menuets and a lively gigue to finish. Students may recognise some of the dance movements from elsewhere and will appreciate the opportunity to place them in context.

Southworth's suggestions for dynamics and breathing are sensible and musical; a student nervous about following in the footsteps of Yo-Yo Ma and Jacqueline du Pré can use them to develop their own interpretation. The biggest challenges for flute players taking on music for strings are of course breathing and articulation. I discourage my students from ‘apologising’ musically for the necessity of breathing, and suggest they make it part of their expression. As Southworth writes: ‘allow the breaths to become part of the melodic line, which in turn should allow the music to breathe naturally.’ She also encourages the player to visualise the cellist's bow, to think about its speed, direction and weight, and how that can be brought into the flute performance.