It was 25 years ago when I first found myself working as a learning support tutor for GCSE Music composition. I had a profoundly dyslexic student who struggled to write notation even with the stems in the right position, and found writing melodies on a stave near impossible. We did composition solely through him improvising over a given chord structure, recording himself and then finding the notation, on Sibelius, by trial and error.

I have supported students – both neurotypical and neurodiverse learners – in the area of composition for many years. Some would complain about being expected simply to sit at a computer and compose; ‘Blank-piece-of-paper syndrome’ would kick in and they simply didn’t know where to start.

At the same time, secondary school teachers would come to me privately for additional composition lessons (which was impressive!), as their own degrees included very little composition or what they had done, they'd wrestled with. They genuinely struggled to teach the skills involved.

Roll on several years, and, thankfully, there are more flexible routes into composition, using programmes such as GarageBand, Soundtrap, Cubase and BandLab. However, there are still early-career teachers who welcome additional support, and this article hopefully provides useful pointers. It describes a composition activity I do with all my private instrumental students, regardless of whether they are doing GCSE or not. It’s also what I’ve used while teaching composition at secondary level within a school setting.

Structure and models

Secondary school music teachers know that having a structure to a piece of music is essential. The formats and techniques I’ve known them use, and use myself, include the following:

- Minimalism. This is where the composer writes a simple phrase or motif and subjects this to repetition and gradual transformation, often in small steps. Many of the techniques for this are already built into the Sibelius notation programme and include using retrograde, inversions, double-note values (rhythmic augmentation), half-note values (rhythmic diminution), shuffled pitches, and rotated rhythms or pitches. An old GCSE YouTube video explaining Steve Reich’s piece Electric Counterpoint (1987) provides an excellent summary of the techniques used, from drones to ostinato, from layering to augmentation, and from metamorphosis (changing one note or making small changes at a time) to phasing and rhythmic displacement.

- Twelve-tone serialism. Here, the same strategies described above can be used when writing a melody using all 12 pitches of the chromatic scale. Typically for use in atonal music, the tone-row ensures there’s no tonal centre or the Western system of triads. You can get students to write on their scores the name of the technique employed, so that this is clear to examiners.

- Twelve-bar blues. This is perhaps the most-commonly used structure: the 12-bar sequence using chords I, IV and V, pentatonic and jazz scales, syncopated rhythm, improvised solos and various bass vamps. The form can work with a variety of ensembles.

Theme and Variations

My own personal favourite ‘go-to’ structure, however, is the Theme and Variations, which works just as well for ensemble as it does piano. It works extremely well, in fact, with string quartet.

The rest of this article explains how to get students to write a Theme and Variations from scratch, while embedding a knowledge of surrounding composition techniques. It also provides thoughts on making composition accessible, including for SEND students.

1. Creating a portfolio

Encourage your students to find and analyse different examples of great composers using Theme and Variations. Scrap-book these to create a great resource to draw from later, noting that even the great composers borrow ideas from others.

Good examples to start with are Mozart's 12 Variations on ‘Ah, vous dirai-je Maman’ for piano, K. 265; Handel’s Suite no. 7 in G minor, the final movement (Passacaglia), HWV 432; and Handel’s Chaconne in C major, HWV 484 (with 49 variations!).

It’s always interesting for students to explore chaconnes and passacaglias in general, and by a wide range of Baroque composers including Handel, Bach and Pachelbel. In essence, both these forms are the Theme and Variation, and it's a useful exercise seeing the reoccurring strategies as well as the wide variety of technique.

2. Preparing the groundwork

This may sound obvious, but some foundational knowledge is required when grasping how the basic harmony stays the same throughout a Theme and Variations. Most likely, your KS3 curriculum will include teaching basic harmony; if not, this will be needed before getting too far ahead. Do check out MT’s online teaching resources; James Manwaring’s article on composing at KS3 has some great ideas.

Once the basics are in place, consider:

- What chord sequence would work well? You may want to talk about the circle of fifths’ harmonic progression (I–IV–vii–iii–vi–ii–V– I) and how composers used this in the Baroque period.

- What are the different ways to write chords? From distributing the chord among the moving parts (in an ensemble) to static chords, broken chords, ostinatos and usig different rhythms etc.

- Using a chord progression to improvise over. The common sequence I–V–vi–IV, found in so many pop songs, is a good one to practise with. Experiment with using the chords in different inversions and broken-chord patterns. Do ensure that students realise what the harmony notes are, however obvious this sounds; in my experience, students (particularly drummers) sometimes fake understanding and are too embarrassed to admit it’s not clear.

- Writing a melody using non-harmony notes (melodic decoration). Some students instinctively do this, without necessarily knowing this could be a rule. Understanding what’s happening theoretically, however, can help them develop this. The same understanding gives less confident students the tools with which to devise a melody. I like to outline passing notes, changing notes, anticipations, auxiliary notes, and appoggiaturas. I also explain the use of suspension within any of the parts, and pedal notes.

A great resource, in this instance, is Victoria Williams's mymusictheory.com, which explains things clearly and in the context of music examples. As well as free resources, the website includes excellent paid-for resources relating to theory examinations. Also check out How to Teach Composition in the Secondary Classroom, which explores a range of compositional techniques, writing to examination criteria, and genres from the waltz to fanfare, and from film music to theme and variation.

3. Composing the Theme and Variations

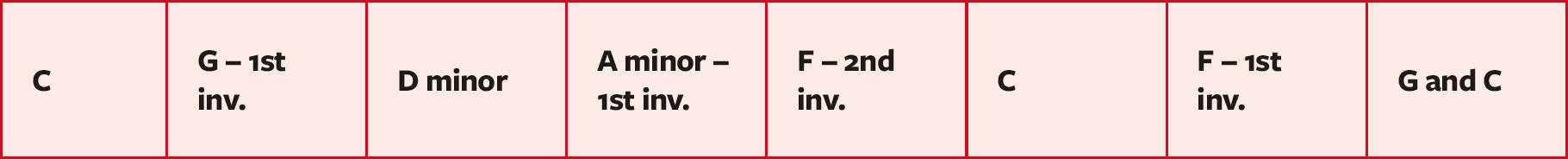

Begin by writing a chord progression. There is nothing stopping students using one by Handel or Bach (being public domain, their music is free of copyright!). In fact, using these composers’ work guarantees strong harmony. Below is an example of an 8-bar sequence by Handel (reproduced from Intermediate Pianist, Book 3, by K. Marshall with H. Hammond).

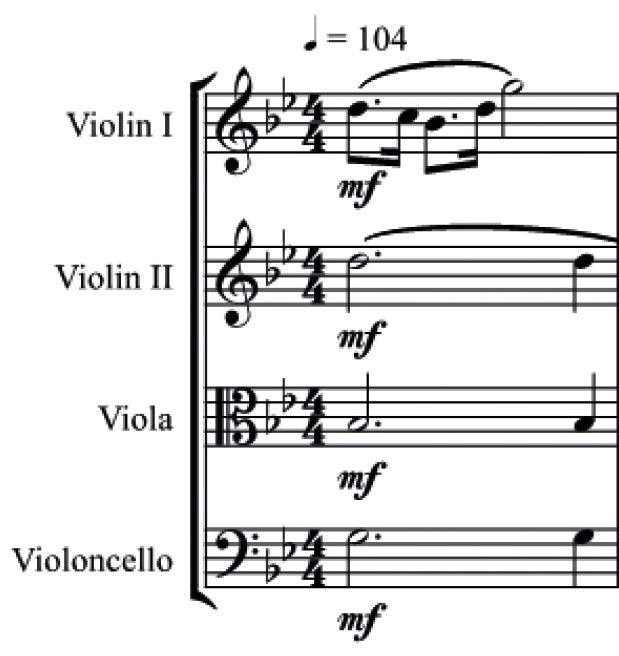

Now invite your students to write the theme, using a basic melody over the simple harmony and an uncomplicated bassline – as in the example below. This is taken from a GCSE student's composition, which is around level 6; it's unedited, not the final version, and used by permission of the student. (The student is dyslexic and has muddled the fonts for dynamic and expression markings, which indicates how some students struggle with notation packages. Now aim for students to write four variations at least; one at a time and showcasing different keys. Moving from the tonic minor to the tonic major, for example, is a very easy key-change to get things started. Also consider a change in time signature, perhaps moving from 4/4 to 12/8 (for reasons that will soon become clear). Figures 2 to 5 are taken from the same GCSE student’s work. In Variation 1 note the basso continuo in the cello part, with supporting harmony in the viola and second violin, all pizzicato. The violin line, meanwhile, contains ornamentation in the form of a turn, drawing attention to the sustained line.

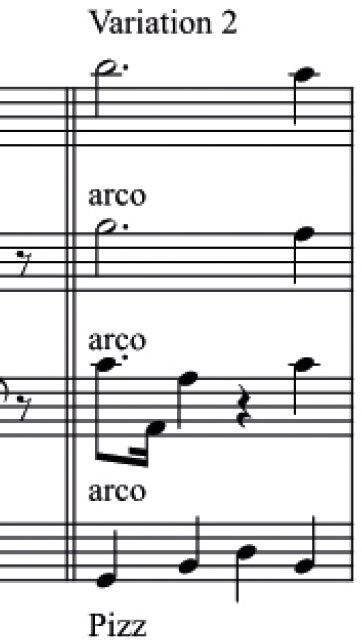

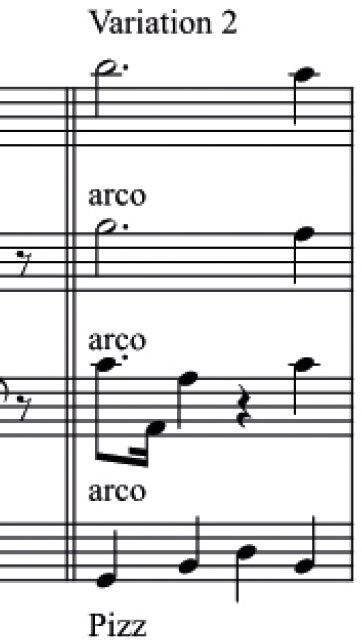

Now aim for students to write four variations at least; one at a time and showcasing different keys. Moving from the tonic minor to the tonic major, for example, is a very easy key-change to get things started. Also consider a change in time signature, perhaps moving from 4/4 to 12/8 (for reasons that will soon become clear). Figures 2 to 5 are taken from the same GCSE student’s work. In Variation 1 note the basso continuo in the cello part, with supporting harmony in the viola and second violin, all pizzicato. The violin line, meanwhile, contains ornamentation in the form of a turn, drawing attention to the sustained line.

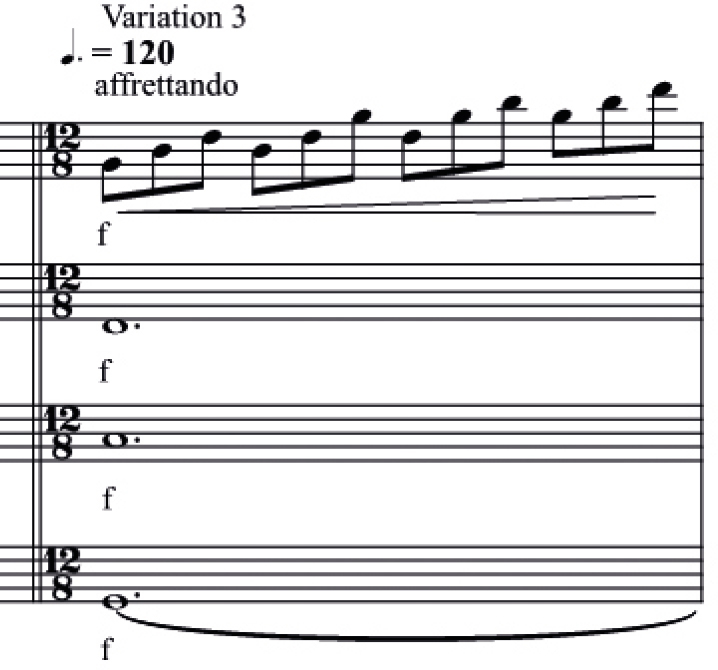

In Variation 2 the bowed first and second violins harmonise, the cello continues pizzicato, but the viola introduces a rhythmic figure. In Variation 3, the student has made a feature out of a rising broken chord, contrasted with a static held chord and pedal note. An opportunity presents itself for the time signature to change to 12/8.

In Variation 3, the student has made a feature out of a rising broken chord, contrasted with a static held chord and pedal note. An opportunity presents itself for the time signature to change to 12/8. In Variation 4 the student has this time used a falling broken-chord pattern; and there’s a modulation to the tonic minor, once again over a pedal note. I am aware of the unresolved seventh in the viola part and how this isn't permissible in a strict classical sense. This can be fixed as part of a discussion about ‘line’, however, and making fewer jumps.

In Variation 4 the student has this time used a falling broken-chord pattern; and there’s a modulation to the tonic minor, once again over a pedal note. I am aware of the unresolved seventh in the viola part and how this isn't permissible in a strict classical sense. This can be fixed as part of a discussion about ‘line’, however, and making fewer jumps. Finally, after the last variation, encourage students to restate the Theme but with some variety to make it memorable as the concluding passage. This can be in the form of additional ornamentation, a change to the rhythm of the melody, more non-harmony notes, or a change to the rhythm of the harmonic accompaniment. In our working example, the student simply reinstated the original theme; but after further sessions, chose to refine it.

Finally, after the last variation, encourage students to restate the Theme but with some variety to make it memorable as the concluding passage. This can be in the form of additional ornamentation, a change to the rhythm of the melody, more non-harmony notes, or a change to the rhythm of the harmonic accompaniment. In our working example, the student simply reinstated the original theme; but after further sessions, chose to refine it.

Composition often requires a period of reflection: living with the work, reacting to musical changes of heart as these occur, and adjusting formal aspects as necessary. In the end, only the composer knows when the work is finished.

When teaching composition to neurodiverse students

Give explicit instructions. Provide a step-by-step map for producing a composition. Make sure you model it as a whole-class activity first. Check students’ understanding though ‘teach me’ approaches. Move from supported to independent working in a step-by-step approach. Aid understanding by doing things practically on an instrument or with technology.

Employ cognitive and metacognitive strategies. Don't give students too much to do at once; manage the load. Write the chord sequence, work on the melody, then compose one variation at a time. Help students plan the tasks needed to finish the work. Encourage improvisation throughout KS3 as a way into composition, so it becomes second nature. Have a means of recording, so that improvisations can be saved and revisited as sources for future compositions.

Scaffold. Provide chord grids indicating the notes of a chord in a particular key, and the inversions. Also consider sets of tempo, dynamic and articulation markings to draw upon. If created, the portfolio of example variations by well-known composers is excellent for scaffolding.

Group students strategically. Work out the groups of children within the classroom or additional intervention groups which are most likely to work best together.

Use technology. Music tech can really help, from simply notating music correctly to being able to improvise and having this captured then notated. Students themselves are often the best source for learning about new apps.

Links and references

- YouTube: Minimalism Music Techniques

- mymusictheory.com/harmony/decoration

- Manwaring, J. (2022) Approaches to composing at KS3, Music Teacher

- Shapey, R. (2021) How to Teach Composition in the Secondary Classroom: 50 Inspiring Ideas. Collins Music.

- EEF blog: Five-a-day to improve SEND outcomes