For most of us, teaching beginners is inevitable and, if we're honest, can be difficult or frustrating. However, it is also a privilege and, if we get it right, it can give children a love of music that can last a lifetime or even lead to a career in music. After all, we were all beginners once.

Music in schools is going through a challenging time, and this applies to instrumental as much as classroom lessons. Ofsted's music subject report (2023) found that many schools had reduced subsidies for instrumental music lessons, leading to a divide between opportunities for children whose families can afford to pay and children whose families can't.

The ISM report Music: A Subject in Peril?, published in anticipation of the government's refreshed NPME (2022), called for more funding for instrumental and vocal tuition, citing a teacher survey and how peripatetic teachers felt lessons should be free or heavily subsidised to ensure that cost was no barrier to learning.

The issues of poor funding and school support still lead to problems with recruitment and retention of instrumental learners. But once new pupils have started, how do we encourage them to keep going – to go beyond the beginner stage, to practice, to want to play with others?

Of course what we teach is important; but how we teach it is crucial. Being a reflective practitioner – continually revising our approaches to teaching – is crucial to keeping lessons engaging and relevant.

Choose the right repertoire

Playing an instrument should be fun, right? Repertoire selection is fundamental to keeping children engaged.

I often use backing-tracks, which bring structure and authenticity to simple pieces, particularly when beginners are playing just one or two notes. I write a lot of music for beginners, all tried and tested on my pupils, and my recent Dinosaur Stomp pieces are going down well with players from Years 3–6 because they like the sound effects on the backing-tracks and can focus on just a few notes at a time during the early tunes.

Thereafter, when selecting pieces, the pathway should be developmental, with a gentle focus on different techniques. New notes can be introduced to gradually increase range and stamina, and space can be introduced for improvisation. Dinosaur Stomp is an example of how beginners' repertoire can progress in breadth, through a variety of styles from rock to tango via Indian classical, and in depth, exploring technique and musicianship in a fun way with authentic-sounding backing-tracks.

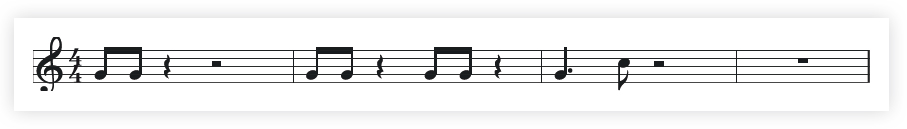

It is important to explore music from a diverse range of genres. Take jazz, as an example. For inspiration, while setting up, listen to music by great musicians such as Miles Davis or Duke Ellington. Try playing a simple tune to get started, such as Miles's ‘So What’ or The Duke's ‘C Jam Blues’, where only two notes are required but timing is everything. The second of these tunes is one simple phrase, repeated twice over the blues sequence:

The momentum and success of this tune come from a strong sense of swing and timing.

To enthuse your players, immerse yourselves in the idiom. ‘C Jam Blues’ is a swing tune, so count in like a jazz musician: click or clap on beats 2 and 4, and give a two-bar count-in of ‘1, a 2, a 1, 2, 3, 4’. In addition, use jazz terminology to describe the music. The main tune is called the ‘head’, for example, and musical phrases are ‘riffs’. Call your practice a ‘jam-session’ and play and improvise stylistically, where you can, like real jazz musicians. Familiarise yourselves with the style through further listening.

Improvisation

Many teachers are nervous about improvising. Depending on your training, you may never have needed to make up music on the spot before, yet this is fundamental to learning an instrument and being creative. This ‘musiking’, just as with dancing, can bring great enjoyment. Fear can stop us being adventurous, but give it a go; remember that you don't have to be an expert. Try starting with some free playing over a drone, where there is plenty of space to develop technique and listening skills while being creative. Play a slow, spacious phrase and ask your students to copy you. Now, play a phrase and ask them to improvise a response. For practising improvisation, try using the online backing-tracks listed left.

Learn by ear or from notation?

Both are useful skills when it comes to playing music, but we all know wonderful musicians who can do only one of these things well. In lessons, I like to employ a mix of both, and avoid having the reading of notation become a barrier to progress, including in the early lessons. I often start lessons with ‘copy-backs’, gradually introducing pentatonic scales alongside the blues scale and the traditional major/minor scales. This work builds on aural skills and technical facility, and is the foundation for confident improvising and finding your way around the instrument without ‘the dots’. ‘C Jam Blues’, with its simple repeated riff, is one to pick up by ear, and can make beginners feel they are playing ‘real’ music.

Practice

Establishing a practice routine can be challenging. It needs the full support of parents – encouraging, cajoling and offering incentives to encourage regular playing at home.

To achieve this, pupils and parents need to know what should be practised (via a notebook or message) and understand how to practise (metacognition, or understanding how to learn). Of course, home practice is more likely to be achieved if the music is fun and feels relevant.

For measuring progress, I find Paul Harris's suggestions for goal-oriented practice particularly effective. In a technique celebrating personal bests, for example, he asks: ‘How many pieces/songs can I perform confidently at the moment?’ or ‘How many times can I play G major remembering the F sharp?’ For small musical challenges or ‘Mini Outcomes’, meanwhile, Harris asks: ‘Can I play this piece with really vivid dynamic contrasts?’ or ‘Can I memorise the first five notes of this scale?’ Such benchmarks provide effective incentives and avoid simply marking time.

WCET and beyond

In the case of ultimate beginners – as experienced with whole-class ensemble teaching – it's not easy to keep everyone engaged when the students are given no choice over which instrument they learn. Progress can feel slow. On the other hand, it's important to define what we mean by ‘progress’: is this more notes, more tunes, better technique, or wider engagement with musical ideas or musicianship?

WCET is a great way to learn as long as lessons are creative and engaging for all. If some pupils struggle even to make a sound on their instrument, they should still feel involved in musical learning. As you reflect and plan for the next lesson or stage of learning, make sure that differentiation is built-in to enable participants to reach their potential, whatever their strengths or struggles.

Progression and performing

Encouraging children to move beyond early lessons into small group music-making is the next step. Schools and music hubs should have strategies in place to support this, with the NPME stating that ‘there should be a discussion at the end of every [WCET] programme about how best to support pupils wishing to continue their learning and this should be captured in the school Music Development Plan’.

Playing with others should be fun and inspiring, and make all of that practice feel worthwhile. With the right repertoire, this can be achieved with just a handful of notes. Ensembles can be really rewarding for teachers and pupils alike, and performances can raise the profile of teachers and departments within the school.

If you get the chance, playing alongside professional musicians can also really motivate. At a recent primary jazz project I ran, a Year 4 student commented: ‘I really loved it, and hope that we meet the jazz people again!’

So, with planning and strategies in place for fun lessons, with the right repertoire and lots of creative work and performance opportunities along the way, it's possible, I believe, to keep the beginners going and going.

Backing-tracks and further reading

- tinyurl.com/ye28kwth (for ‘C Jam Blues’)

- tinyurl.com/3389t5xk(a drone, for use with notes from A minor pentatonic)

- youtube.com/user/Jimcdooley (drum beats in various styles and tempos)

- paulharristeaching.co.uk/blog/tag/progress