Teaching rhythm in the western musical tradition is often an ad hoc business. This addresses problems as they arise and hopes that by the time a student gets to professional level, enough rhythm has been learned to be able to work out and play through anything the student comes across.

However, there are ways of being systematic about learning rhythm, and approaching this the same way that arithmetic is taught – in stages. Counting, for instance, can come before adding, which comes before multiplication.

The basics

By breaking down the stages and skills encountered at a professional level, we can prepare our students to be able to decode and perform anything that is put in front of them. Here are the main skills, listed in order of how they could be taught:

- Keep a steady pulse

- Count the pulse

- Subdivide the pulse into 2, 3, 4, 5 etc.

- Feel accents

- Reproduce rhythmic patterns

- Displace a rhythmic pattern

- Hold one pattern against another

- Synchronise our sense of the beat with other musicians.

To demonstrate the first of these, try walking, feeling the regularity of your steps. Count aloud the steps as ‘one, two, one, two… ’, and at different speeds. Accent the ‘one’ when you say it, then accent the ‘two’ instead. Now try replacing the ‘one’ and then the ‘two’ with a gap, or rest.

In class, I like to explore feeling the pulse by getting students to walk and count. There are a lot of places to put one's attention. We can focus on the moment the foot touches the ground, the space between steps, the synchronicity of the voice with the steps, or the tempo, which we can increase or decrease. Then we can add accents, making one foot stronger than the other, or count in threes and accent each third step.

There are plenty of ways to conceptualise rhythms. Drummers are typically taught to divide a beat into four 16ths (semiquavers), naming the beat and subdivisions ‘one-ee-and-a, two-ee-and-a’, and so forth. The British drummer Mark Mondesir tells me that he thinks in circles: once around the circle is equivalent to one beat, and the subdivisions are points at regular intervals on the circle. In this way, he can access any number of subdivisions of a beat, or even number of beats.

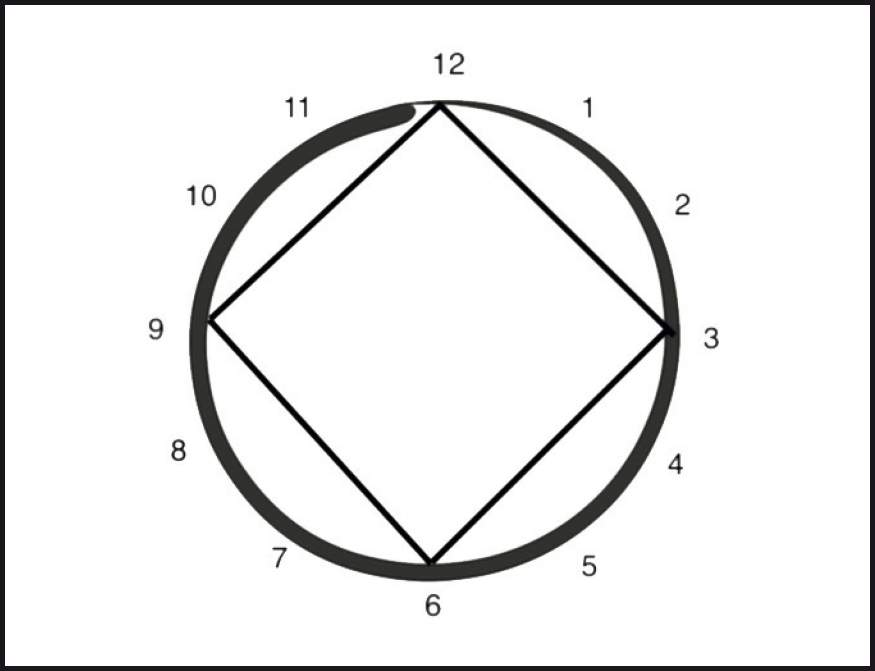

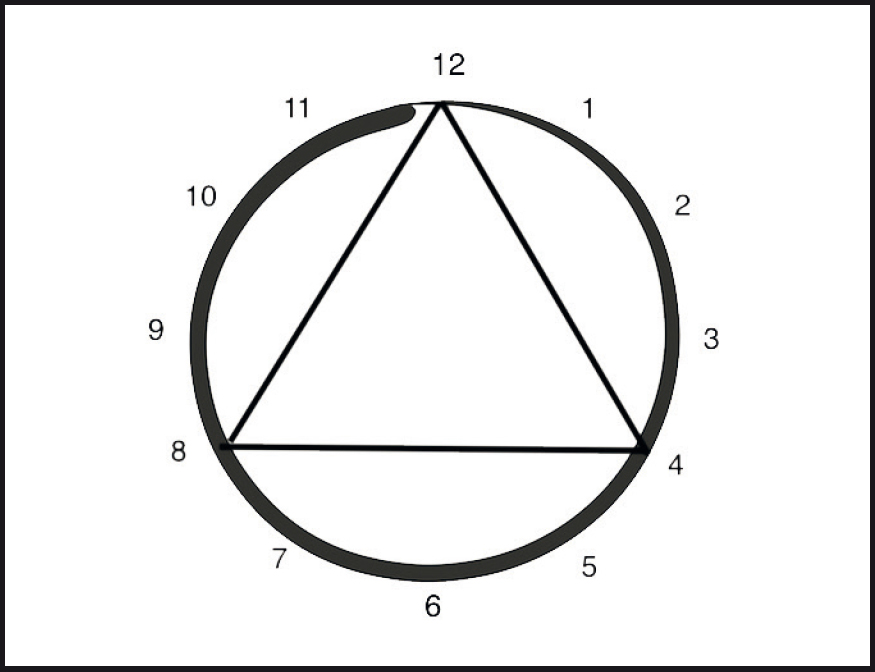

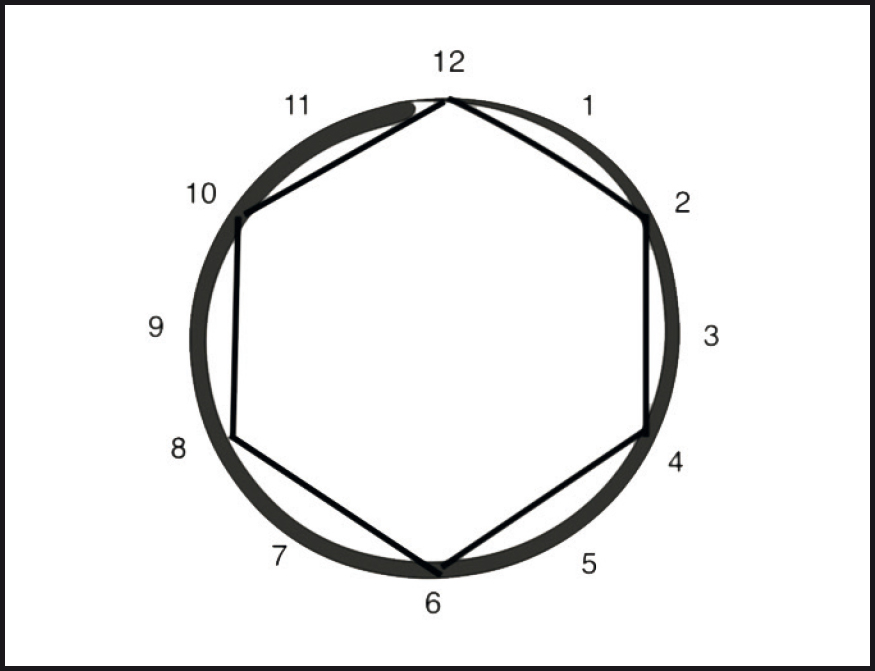

Let's explore some circular subdividing. Imagine a clock face. The hour-hand starts at 12 and completes a circle – that is one beat. To divide the beat into two, imagine a marker at 6 o’clock. To divide the beat into four, have markers at 12, 3, 6 and 9; into three, have markers at 12, 4 and 8; and for six, it's 12, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10, as shown in the following figures:

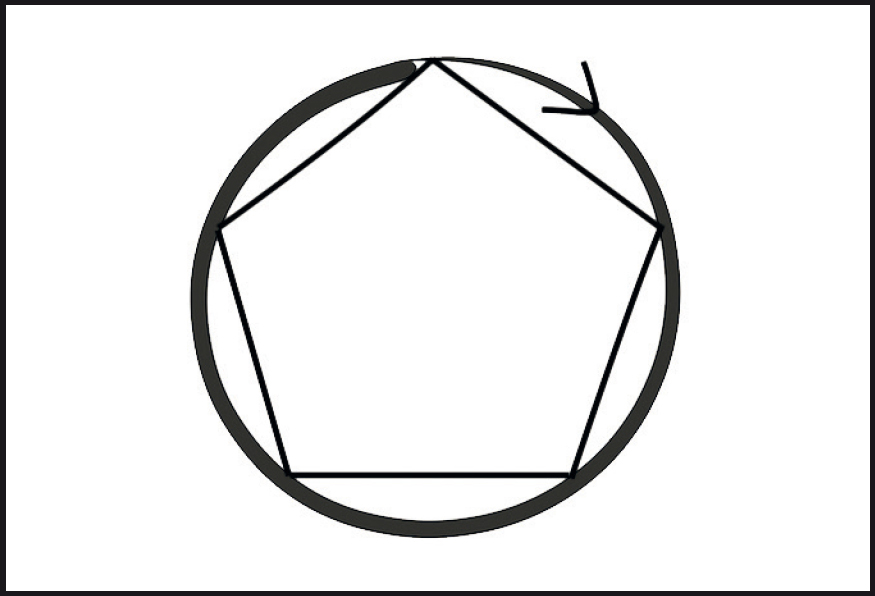

Using the circle, we can also divide the beat into five by imagining a pentagon inside the circle:

Using syllables

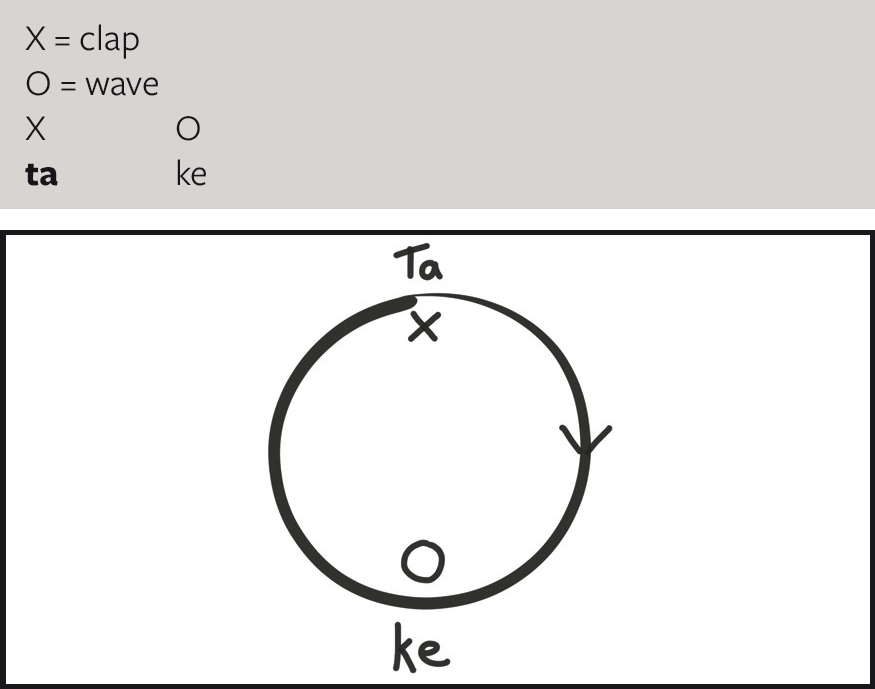

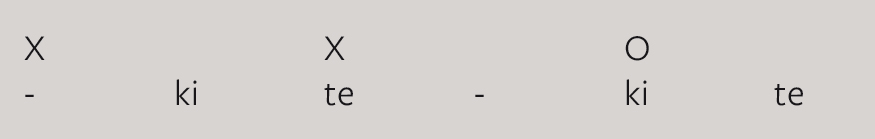

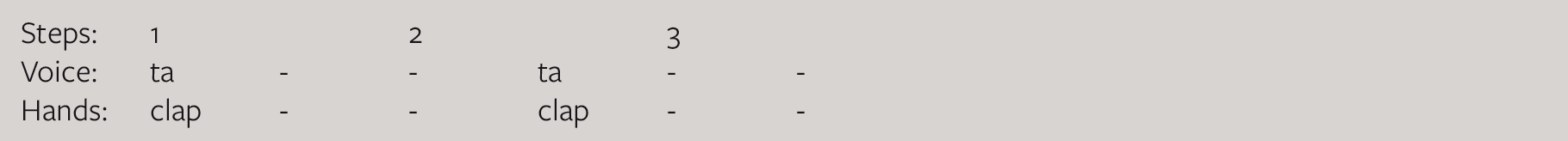

Another way of practising subdivisions is to use spoken syllables. In the Carnatic rhythmic system from South India, the bar (or time-cycle) is marked with hand gestures and the rhythms are spoken before being played. A fundamental unit of two beats is called a drutam; it consists of a clap and a ‘wave’. The wave is usually realised by tapping the back of the right hand onto the left palm.

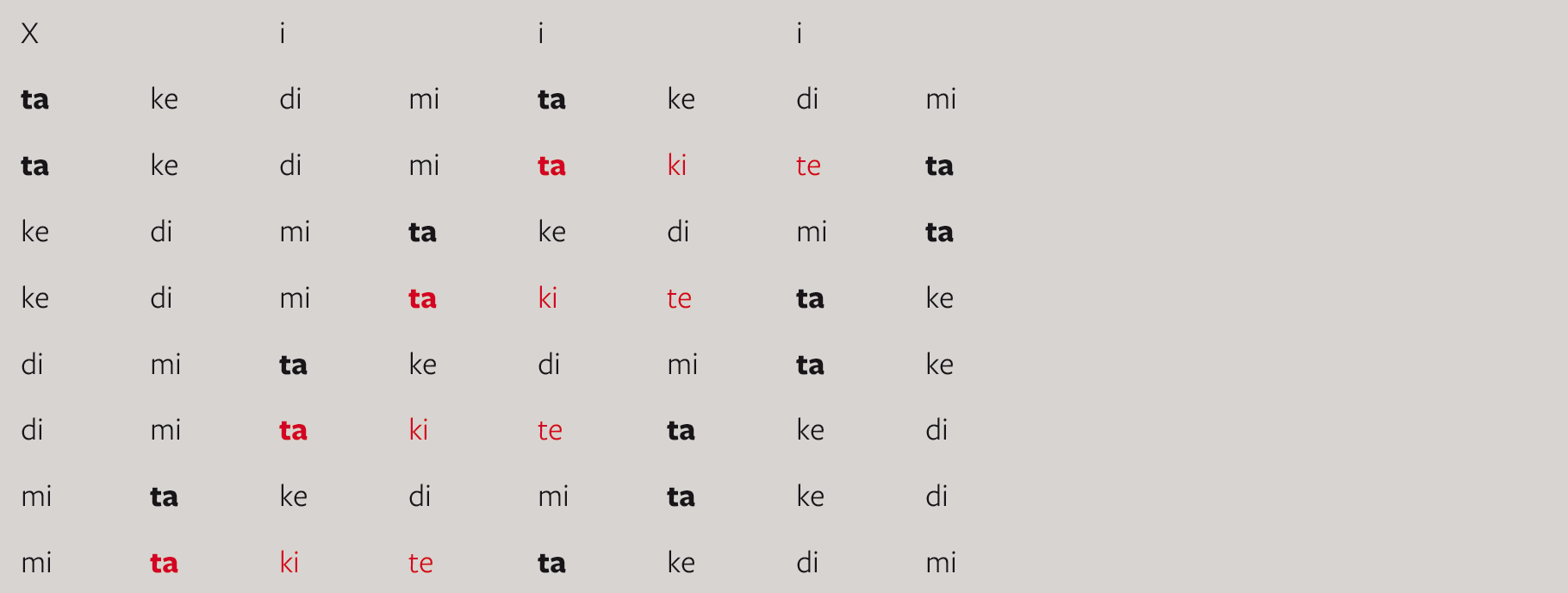

If we say ‘ta’ as we clap, and ‘ke’ as we wave, we are speaking each beat in a bar of two beats:

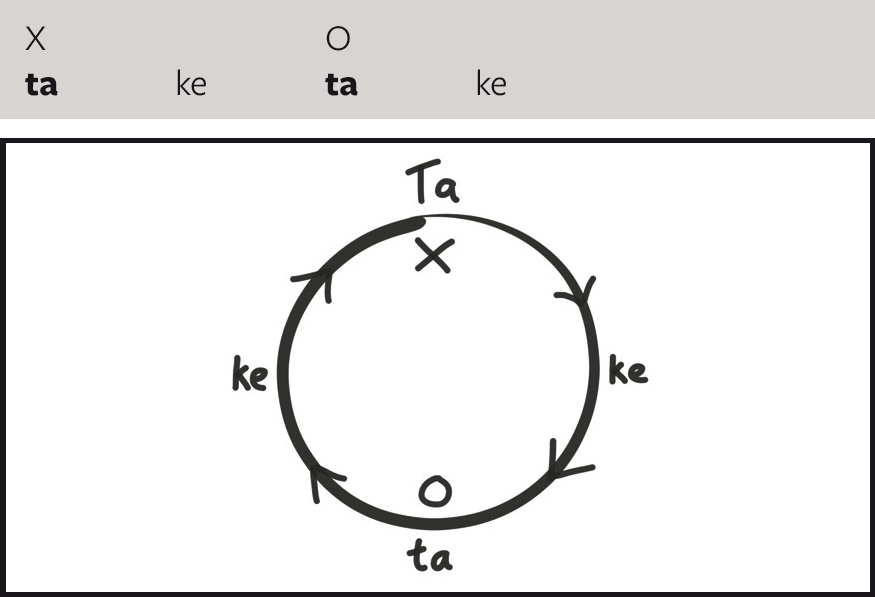

Let's now try doubling the speed of the syllables, while keeping the hand gestures the same:

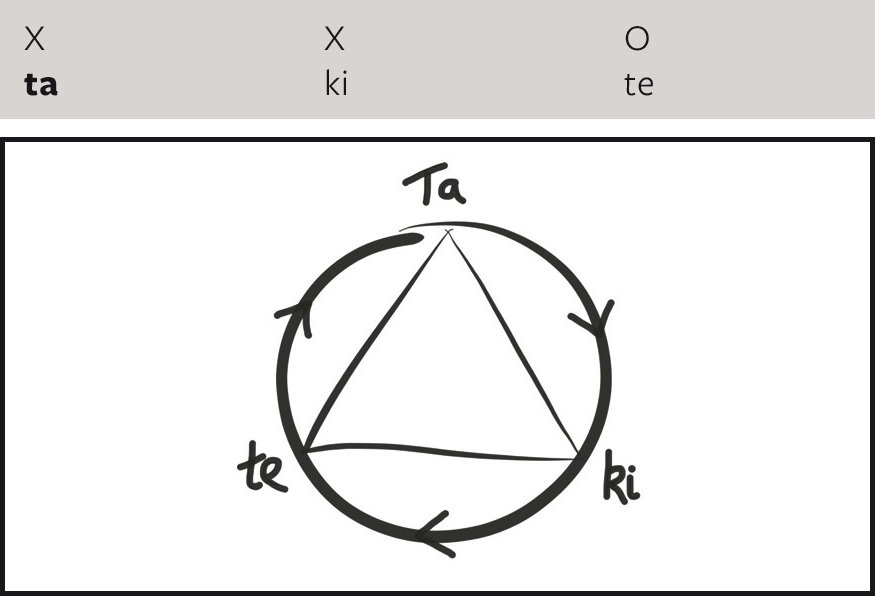

Now try clapping a three-beat cycle and saying three syllables, one per beat:

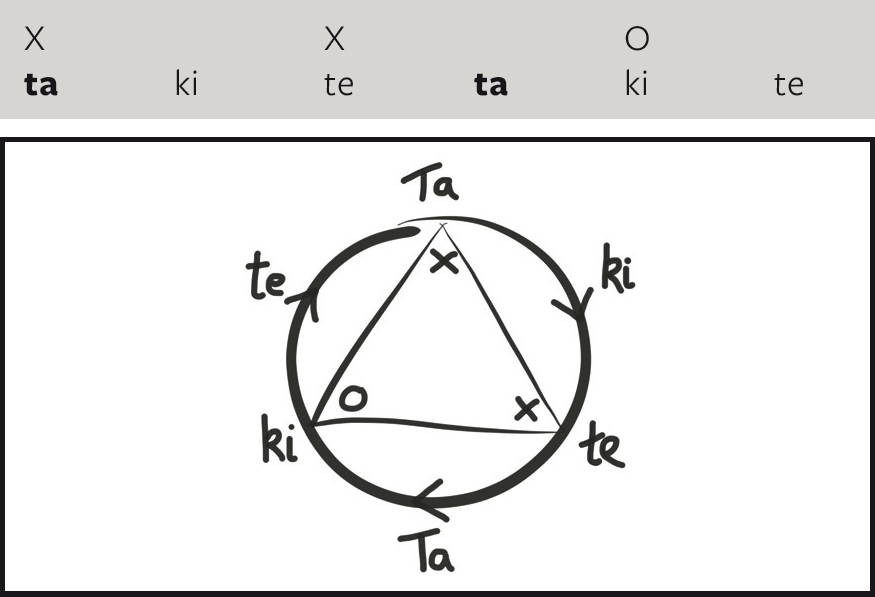

When we double these syllables, the second ‘ta’ falls between two beats:

We can use this as an exercise to practise two-against-three. If we leave gaps instead of saying ‘ki te’, we get:![]()

And if we replace the ‘ta’ with a gap, we get:

Reinforce with steps

A good way of getting this more into our bodies is to walk the beats, and either clap or say the rhythms. To step in three beats, we place the right foot forward on beat one, come back onto the left foot on beat two, and bring back the right foot on beat three. Then, for the next bar, mirror this: place the left foot forward on beat one, come back onto the right foot on beat two, and bring back the left foot on beat three.

Try speaking ‘ta ki te’ along with the steps, one syllable per step, then double the speed of the speech as before.

A great game is to get several people in a circle, all stepping together in three. Say the ‘ta’ from the doubled speech one-by-one around the circle, then replace the spoken ‘ta’ with a clap, again one-by-one around the circle:

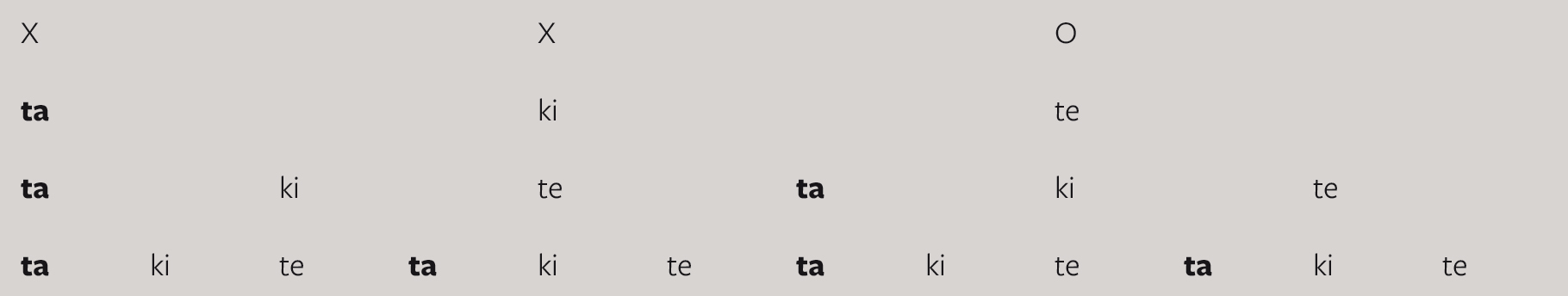

Four-against-three

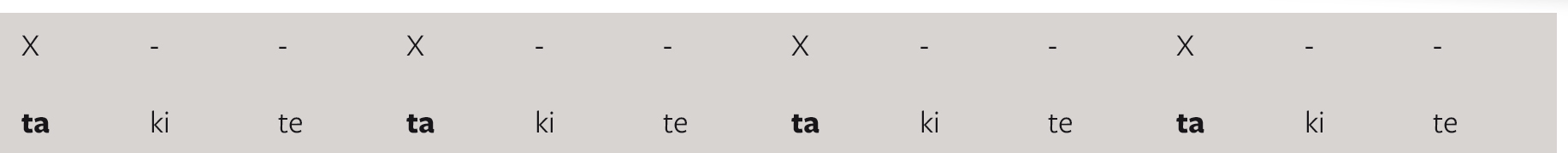

Now let's look at four-against-three. Starting with the hand gestures for three beats while speaking ‘ta ki te’ (one syllable per beat), double as before, then double again:

Concentrate on the ‘ta's and then replace the ‘ki te's with gaps:![]()

Displacement exercise

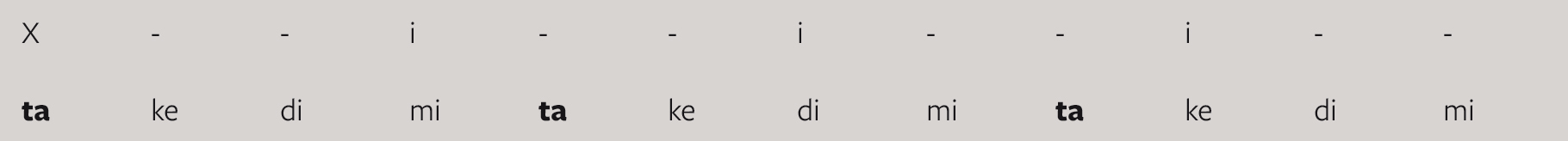

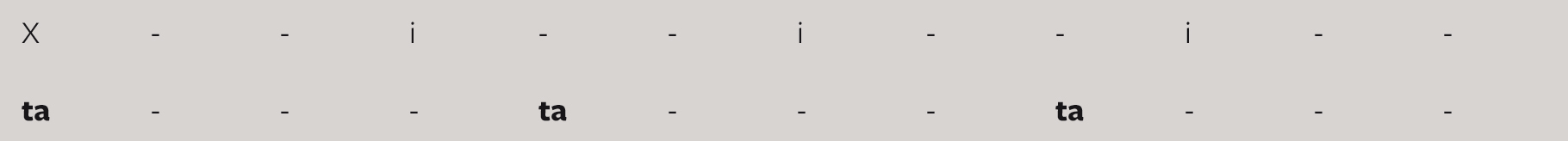

Let's start by using our hands to describe a four-beat cycle, here written as X i i i. Clap on the first beat. Then touch the left palm with the right little finger for the second beat; the ring finger for the third beat; and the middle finger for the fourth. Finger touches are represented by the small letter i.![]()

Now, it's time to introduce a four-syllable group: ‘ta ke di mi’. To prepare, start by speaking one syllable per beat, then double the speed:![]()

Here is the displacement exercise using the double-speed syllables. We will say ‘ta ke di mi’ three times, ‘ta ki te’ once, then repeat the whole thing another three times:

This exercise is very useful for feeling accents in all the awkward places in a bar. When you get comfortable with it, try this at double speed, which means one ‘ta ke di mi’ per beat.

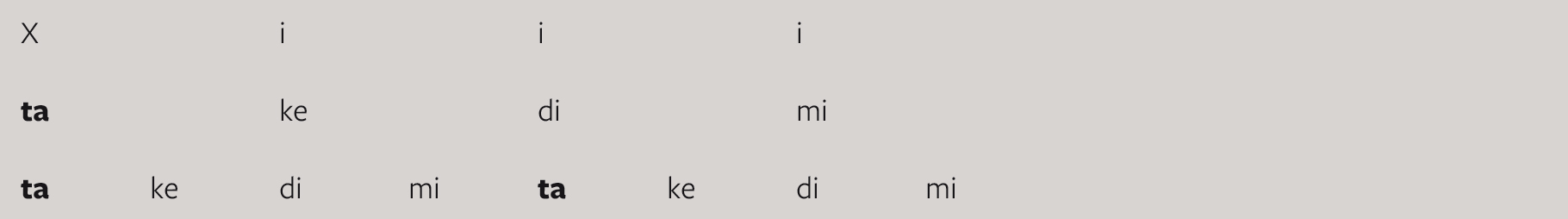

Three-against-four

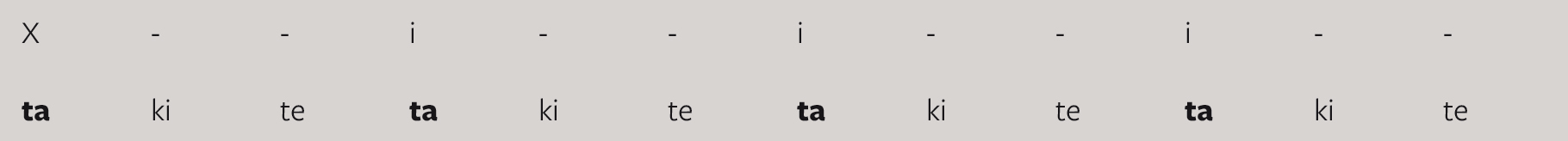

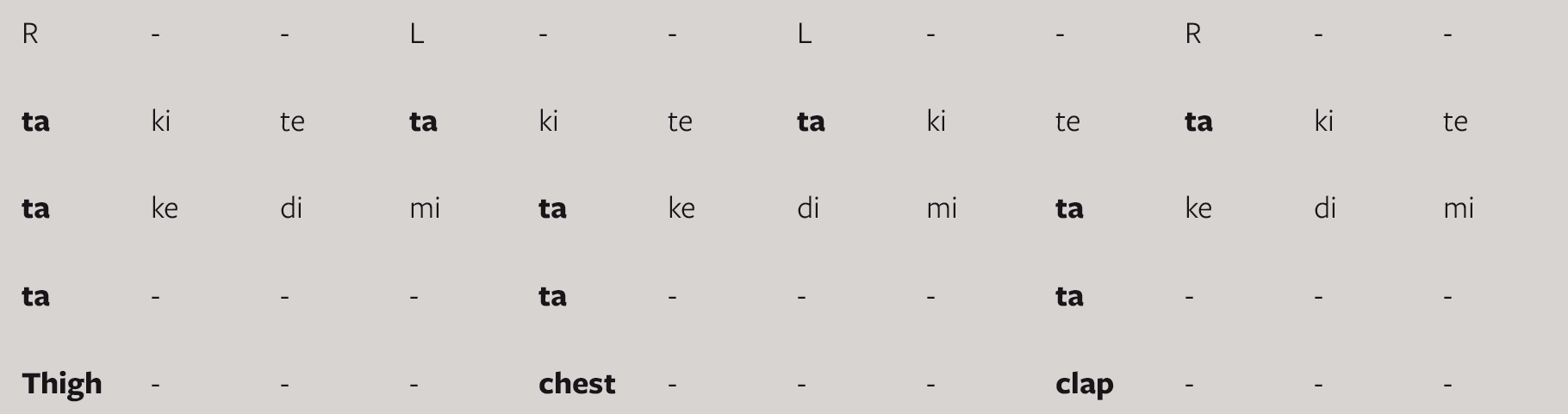

Finally, it's time to explore three-against-four. First, we need to divide each beat into three. I have a failsafe process for this: count in threes, saying ‘ta ki te’, then add to this a clap followed by the little finger to palm, and ring finger to palm:

Now repeat this over and over, gradually getting faster, until it's too fast for the fingers. Then leave the fingers out:

The last step is to replace the second, third and fourth claps with the fingers as before, starting with the little finger and finishing with the middle one:

Now for the three-against-four. We need to say ‘ta ke di mi’ at the same speed as the ‘ta ki te's:

It is important to accent each ‘ta’ in order to feel the three-against-four correctly. We can leave out the ‘ke di mi’ to get the full experience:

This is also a great exercise to put into the body while stepping in a cycle of four beats. I suggest starting with the feet together. On beat one, step the right foot out to the right. On beat two, lift the left foot and step it towards the right foot. On beat three, step the left foot back to its first position, and on beat four, bring the right foot back beside the left foot. This movement replaces the hands in the previous exercise. We can say ‘ta ki te’ together with the steps and then change to ‘ta ke di mi’ to make the three-against-four. I like to replace the spoken ‘ta's with some body percussion. See if you can follow this summary:

You can make endless variations of this, especially with groups. How about having one group step in four and speaking the first line? The ‘ta’ coincides with the feet. Then, a second group speaks the second line and starts stepping in three, also synchronising the ‘ta’ and the feet.

I hope this has given you a good introduction to thinking in circles and using syllables, hand movements, stepping and body percussion to develop rhythm skills. Feeling and expressing rhythm physically, from the ground up, rather than reading notation, brings huge benefits and makes for faster progress.